Holding

In Wagner v. Ashline, No. 21-1715 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 17, 2021), the Federal Circuit affirmed the Western District of North Carolina's decision to grant summary judgment against Ms. Wagner, agreeing with the district court that she failed to provide sufficient corroboration of her claim of joint inventorship under 35 U.S.C. § 256.

Background

In 2001, Ms. Wagner began work on a safety vest for children having shoulder flaps that confine the strap of a seatbelt to maintain a proper slope across the child's body to reduce injury from serious car accidents (the "Guardian Angel Vest"). Around the same time, Mr. Ashline began developing a head and neck restraint (HNR) device for reducing serious injury during a high-performance vehicle collision.

Ms. Wagner and Mr. Ashline crossed paths in 2003, when Ms. Wagner visited Mr. Ashline's workplace and discussed testing the Guardian Angel Vest. She inquired about the possibility of Mr. Ashline's company manufacturing her vest, left a physical prototype of the vest with him for evaluation purposes, and considered herself to have an "ongoing collaboration" with him to continue developing the vest. The relationship ended turbulently in 2006, when Mr. Ashline's wife had an argument with Ms. Wagner, stating that Mr. Ashline was working on his own device, and demanding that Ms. Wagner retrieve her prototype Guardian Angel Vest from the Ashline residence.

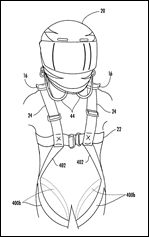

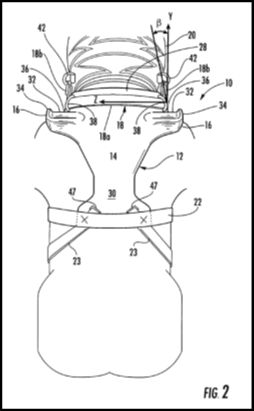

In 2010, Ms. Wagner discovered that Mr. Ashline had filed a patent application on his HNR device, and testified that when she saw the application, she "just knew it had shoulder portions." Mr. Ashline's patent issued in 2012, as U.S. Patent NO. 8,272,074 ("the '074 patent"). Claim 1 of the '074 patent recites "a member having shoulder portions at least partially positionable on top of at least a portion the shoulders of the driver." See also, Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, below.

|

|

Caption: Fig. 1 and Fig 2. of the '074

patent. The "shoulder portions" alleged to have been

contributed by Ms. Wagner are indicated by reference number 16 in

Fig 2.

Ms. Wagner alleged that she contributed to the "shoulder portions" limitation recited in claim 1 of the '074 patent, and sued Mr. Ashline and his company, Simpson Performance Products, Inc., to whom he had assigned the '074 patent, seeking to be added as a joint inventor.

Federal Circuit Decision

The Federal Circuit began its analysis by noting that "[a]n alleged co-inventor's contribution to a claimed invention must be proven by clear and convincing evidence." Citing Ethicon, Inc. v. U.S. Surgical Corp., 135 F.3d 1456, 1461 (Fed. Cir. 1998). "It is well established in our case law that a party claiming joint inventorship must proffer evidence corroborating her own testimony. This is because oral testimony of the alleged co-inventor on its own will generally not suffice as 'clear and convincing' evidence of joint inventorship." Citing Price v. Symsek, 988 F.2d 1187, 1194–95 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

Ms. Wagner relied on three pieces of evidence to support her claim of co-inventorship. First, she pointed to the parent patents of the '074 patent, noting that they did not contain the phrase "shoulder portions." Ms. Wagner argued that only the applications that Mr. Ashline filed after their series of meetings used such terminology. According to Ms. Wagner, this evidence corroborates her testimony that she contributed the "shoulder portions" concept. However, the Federal Circuit did not find this argument persuasive, noting that although the parent patents did not expressly refer to "shoulder portions," the concept of shoulder portions was disclosed in the parent patents.

Next, Ms. Wagner relied on the deposition testimony of a witness, Mr. Cooksey, as corroborative evidence. However, Mr. Cooksey's testimony only covered the details of a single meeting between Ms. Wagner and Mr. Ashline that focused on the Guardian Angel Vest and Ms. Wagner's idea for a children's book. The court held that this testimony was too limited in scope to provide sufficient corroboration of Ms. Wagner's contributions to the '074 patent.

Finally, Ms. Wagner relied on Mr. Ashline's deposition testimony regarding their meetings, arguing that his testimony corroborates that she explained the "shoulder portions" concept to him. The court disagreed and explained that Mr. Ashline's testimony at best demonstrates that Ms. Wagner and Mr. Ashline met and spoke several times over a period of three years, during which Ms. Wagner sought and received guidance from Mr. Ashline regarding her vest and/or a series of children's books. However, none of his testimony demonstrated that Ms. Wagner made any meaningful contributions to the '074 patent.

After reviewing each of these proffered items of evidence, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court's judgment of no joint inventorship and concluded that "even when viewing all reasonable inferences in Ms. Wagner's favor, Ms. Wagner did not present sufficient evidence of corroboration to support her claim of co-inventorship as a matter of law."

Takeaways

"The threshold question in determining inventorship is who conceived of the invention." Mueller Brass Co. v. Reading Indus., 352 F. Supp 1357(E.D. Pa 1972). Conception is often referred to as the mental part of the inventive activity, and it requires a recognition of the ultimately desired result and the means to accomplish that result. See Sewall v. Walters, 21 F.3d 411, 415 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

- Inventorship of a patent is important, and if an omitted inventor makes an evidentiary showing sufficient to establish that she should be named as a co-inventor on a patent, she will enjoy a presumption of ownership of the entire patent, even if her contribution pertained to a single claim in a patent having multiple claims.

- While an alleged co-inventor's contribution to the conception of a claim must be proven by clear and convincing evidence, there is no requirement that every detail of an alleged inventor's testimony be corroborated.

- However, an alleged co-inventor must present sufficient independent evidence, outside of her own testimony, to corroborate her assertion of contribution to the conception of the invention as claimed. Evidence that merely demonstrates conversations between the alleged co-inventor and actual inventor regarding the invention or discussions of the prior art may not be sufficient to prove co-inventorship.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.