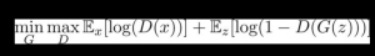

In October of 2018, Christie's sold the work Portrait of Edmond de Belamy for $432,500. None of this, including the price, would be notable if not for the claimed artist. The claimed artist was not a person but an algorithm, bearing its creator's signature:

Obvious, a Paris-based collective, created the work using what is known as Generative Adversarial Networks, or "GANs." Creating works using GANs requires inputting thousands of images as well as developing and making adjustments to the algorithm.

The sale, which garnered attention and outrage alike, served as a flashpoint in the discussion of artificial intelligence and art. As Ian Bogost of The Atlantic wrote, "[t]he image was created by an algorithm the artists didn't write, trained on an 'Old Masters' image set they also didn't create."

In the aftermath of this sale, Sotheby's followed suit with the sale of Mario Klingemann's Memories of Passerby I (2018) in March of 2019. The work, which sold online for roughly $42,000, uses multiple GANs trained on thousands of portraits from the 17th to 19th century to generate an infinite stream of real-time portraits for the viewer. Klingemann refers to the neural networks used to create an endless stream of new images as "the brushes that I've learned to use." Memories of Passerby I may not have generated the same buzz as Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, but it raises many of the same questions.

Although the use of technology to create art is nothing new, GANs, and similar neural network software, increasingly blur the lines when it comes to creation, authorship and ownership. The use of technology such as GANs to create art results in works that are not authored by individuals in the traditional sense. The question then becomes, are these works copyrightable under U.S. Copyright laws, and if so, to whom does the copyright belong?

Only a Person Has Standing to Sue under U.S. Copyright Law

In the Ninth Circuit only a human has standing to sue under the Copyright Act. In Naruto v. Slater, 888 F.3d 418 (9th Cir. 2018), the Ninth Circuit explored the question of whether "selfies" taken by a monkey using equipment set up by a nature photographer were protectable under U.S. Copyright law. David Slater, a wildlife photographer left his camera unattended in a reserve in Indonesia. Id. at 420. Naruto, a seven-year old crested macaque took a series of selfies by pressing the shutter button on the camera in which he appeared to be smiling for the camera. Id. Slater subsequently published the "Monkey Selfies" in a book describing Naruto as "[p]osing to take its own photograph, unworried by its own reflection, smiling. Surely a sign of self-awareness." Id. Slater listed himself and the publisher as the owner of the copyright to the Monkey Selfies. Id.

Subsequently, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals ("PETA") and Dr. Antje Engelhardt filed a complaint for copyright infringement as Next Friends on behalf of Naruto. Id. The Ninth Circuit dismissed the case on the grounds that "Naruto – and more broadly, animals other than humans – lack statutory standing to sue under the Copyright Act." Id. at 426. In a partial concurrence, Justice N.R. Smith, expanded on the Court's holding that an animal could not have next friend status noting that "any argument that animals are akin to 'artificial persons' such as corporations, which are allowed to sue, see e.g., Cetacean [Community v. Bush], 386 F.3d [1169, 1176 (9th Cir. 2004)] (concluding that animals are no different from various "artificial persons" such as ships or corporations), makes no sense in the context of 28 U.S.C. § 2242. Corporations cannot be imprisoned and, thus, there is no grounds to conclude "person" in 28 U.S.C. § 2242 could include anything other than natural persons." Id. at 431.

For now, it is clear that only humans have the right to obtain a copyright. This means that works that are wholly generated by a machine, such as GANs, would be unable to obtain copyright protection if the machine is deemed to be the "author" of the work. As the creation of art using artificial intelligence becomes increasingly common, the lines between authorship and ownership as well as original, transformative and derivative works become less clear.

AI's Impact on Ownership, Attribution and Protection

Earlier last year, these questions came to the fore in an incident involving GANbreeder. GANbreeder is a straightforward interface created by Joel Simon to allow non-programmers to create GAN-generated images simply by selecting images and "breeding" together combinations of the user's choosing.

Intrigued by the creative and collaborative possibilities, conceptual artist Alexander Reben, with Simon's approval, created a scraper that allowed him to automatically select images which were then saved to Reben's PC. Images were then selected from the locally saved pool using an algorithm that would choose images based on Reben's body signals. The selected images were then sent to a painting service in China to create canvas works.

Reben believed that the images he was selecting from were randomly generated and not created by other GANbreeder users. Thus, when Reben shared his works to advertise his upcoming gallery shows he did so without any attribution. Backlash quickly followed, with several GAN artists, such as Danielle Baskin, calling Reben out for using work generated by them rather than generating his own. Reben, quickly apologized and ultimately worked out a solution with Baskin by listing the images as sourced from Baskin.

Yet the questions for both Reben's and Baskin's works, along with other pieces generated with the assistance of AI, become who is the author of the work and is the work copyrightable under U.S. law? Neither of these questions has an easy answer.

The Future of Copyright of Works Generated Using AI

The answers to these questions will likely be resolved on a case-by-case basis depending on the AI involvement. If the AI is considered the author of the work, then under current U.S. law the work would not be eligible for copyright protection. To the extent there is human input, the artist could be deemed the author and receive copyright protection for their creation of the work, although the work may be considered a derivative work. When a work is generated using inputs created by other artists, it may therefore be necessary to obtain permission from the contributors before using the generated images. That said, in some instances, it is possible that the platforms that encourage users to generate images using works uploaded by other users may give rise to an implied license. Similarly, works generated using GANs or similar neural network technology could, under certain circumstances, be deemed fair use, even if copyrighted works are used as the input.

For now, any artist using AI to create a copyrighted work should document their efforts to show their creative process and their independent contributions. In this way, the individual artist can make sure that they can receive a copyright for as much of their work as possible.

Originally published 28 May, 2020

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.