Whether you are an owner, design professional, design consultant, construction manager (CM), general contractor (GC), or subcontractor, it is almost inevitable that you will encounter the use of building information modeling (BIM), to one degree or another, in perhaps every design and construction project you are involved in. Many owners today require that all of their projects, regardless of scale or complexity, be designed in BIM. Typically, this decision is based on an assumption that using BIM will:

- Deliver a more complete design;

- Provide a better-coordinated design that is less prone to design errors or omissions;

- Facilitate efficient design variations and changes;

- Clearly communicate design concepts to the contractor;

- Lead to more accurate and timely estimates and schedules for construction; and,

- Produce an accurate, electronic version of the project that can potentially be turned over to the owner.

And, in some instances it does. The promise of accurate, progressive, efficient, virtually error-free design and construction with BIM is real but it is neither inevitable nor easy to achieve. Although the required technology is available and can be utilized, very few projects or project teams are organized or financed in a manner that will capture all of the benefits BIM offers.

Part I of this article described a few key ways in which BIM is used, misused, and misunderstood in design and construction. Part II below describes how one might mitigate these risks through early adoption, planning, clarifying roles, and maintaining accountability of the various parties involved in a BIM project.

How To Mitigate BIM Risks

While there are numerous challenges associated with the use of BIM, there are several ways to manage them and accomplish the ultimate goal of using BIM to deliver more successful projects in an efficient, cost-effective, and coordinated manner. The following strategies can help lay the groundwork for this success:

1. Adopt BIM Early in the Life of the Project

If possible, the owner or GC should communicate to all project stakeholders the intention to use BIM from project inception, with clear and documented concepts about how it will be used. As discussed earlier, a BIM Execution Plan (BIMXP) can aid project participants in understanding their roles and expectations and can contribute to the overall success of the project. Adopting BIM later in the project and without a clear purpose can add confusion, time, and cost rather than yielding benefits.

2. Use Established BIM Contracts and Addenda

There are a variety of contract document forms that are designed for projects using BIM. The standard form contracts developed by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) also include exhibits, tables, and licensing agreement documentation to accompany them. The AIA recently released new BIM and digital delivery contract document forms which reflect modern practice within the design and construction industries. They aim to simplify the roles and process of using BIM on construction projects. These include:

- AIA E201-2022 BIM Exhibit for Sharing Models with Project Participants, Where Model Versions May be Enumerated as a Contract Document

- AIA E202-2022 BIM Exhibit for Sharing Models with Project Participants, Where Model Versions May Not be Enumerated as a Contract Document

- AIA E401-2022 BIM Exhibit for Sharing Model Solely Within the Design Team

- AIA E402-2022 BIM Exhibit for Sharing Model Solely Within the Construction Team

- AIA G203-2022 BIM Execution Plan

- AIA G204-2022 Model Element Table

- AIA G205-2022 Abbreviated Model Element Table

- AIA C106-2022 Digital Data Licensing Agreement

The Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) has also developed an alternative contract form, the ConsensusDocs' BIM Addendum 301, which is intended to address various legal and organizational issues associated with BIM. This document is envisioned to be used as an addendum to contracts developed using the ConsensusDocs format and applies to all participants who may be inputting information into the BIM. It also includes descriptions of the more critical components of a BIM Execution Plan.

The AIA forms and the ConsensusDocs addendum attempt to identify and memorialize the expected and unexpected risks of using BIM. The use of standard contract forms minimizes the risk of conflicting or uncoordinated terms which may cloud the understanding of BIM use and the associated responsibility. These agreements also typically define whether or not the BIM design will be legally considered to be a contract document as well as who may be able to retain possession and/or use of the BIM at the end of the project.

3. Define Design and Modeling Roles as Well as Planned Model Exchanges And / Or Sharing

It is important to clearly define design and modeling roles in advance of performing that work. Using the prior example of Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing (MEP) modeling, if those subcontractors are expected to be responsible for producing a MEP BIM with accurate routing, attachment details, and connections to equipment - and they will not be able to rely upon any 3D models developed by the Design MEP consultant as a basis for their own modeling work - that limitation should be defined in the appropriate contracts.

By way of example, in a recent matter both authors were involved in, the GC relied on a document entitled, "BIM Project Execution Requirements"to identify the roles and responsibilities of its subcontractors regarding BIM. A few of the relevant provisions are included below, with emphasis added:

"Design Model is the model file (or files) provided by the Design team. Typically the Design Model carries a liability waiver, holding the Design Team harmless for the content of the model files. A liability waiver agreement will need to be signed by any trade contractor (Subcontractor) requesting these models and provided to the GC/CM, should such model files be available. Typically, the Design Model is a supplemental effort to the 2D Contract Documents, whether it is used to generate the 2D Contract Documents or not. Whenever an issue may arise which requires definition as to which element is the governing element, it shall be the 2D Contract Document and not the 3D Design Model that shall be the governing element.

Construction Model is a Subcontractor's accurate and complete representation of field construction conditions (whether planned or actual) including all components necessary for complete fabrication and installation. Each Subcontractor's distinct Construction Model files are expected to be clash and error free and provide the level of detail needed in order to extract precise routing geometry and material or object properties.

Should Design Model files be provided for use by the Construction team, Participants understand and acknowledge that under no circumstances should the Participant assume that the files are accurate, complete, or contain the same level of detail as required herein. These files are to be used at the sole risk and discretion of the Participant, and under no circumstances shall the content or timeliness of Design Model files be considered as a justification for requests for additional cost or delay on the part of any Participant."

These provisions were helpful in defining what the subcontractors were to produce in BIM as well as what they would be able to rely on as they produced their own portions of the model, with or without the use of the Design Models. Unfortunately, for that particular project, even with a clear delineation of responsibilities for subcontractors, the poor management and the coordination of the overall BIM process by the GC led to construction impacts and a limited ability for any/all project participants to rely upon the combined or federated model as was originally intended when the contract language was developed.

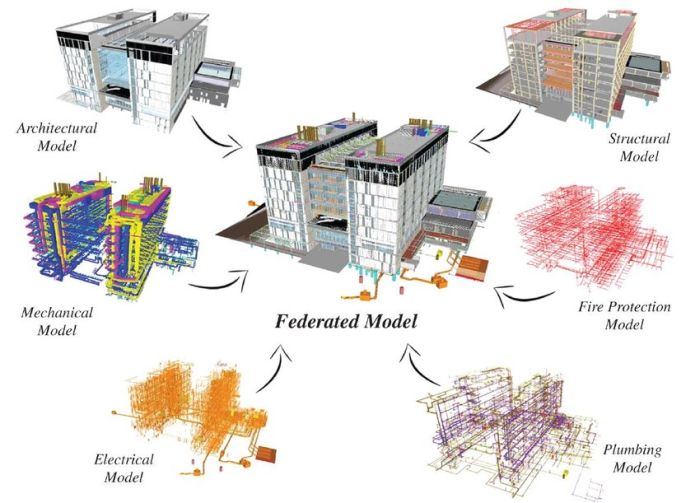

Figure 1: Depiction of a BIM Federated Model (from Quan T Nguyen et al.)

4. Determine What Will Be Modeled, to What Level of Precision, and What Time in the Development of the Design

It is critical that the extent and accuracy of modeling is well defined. While this may be expected to be a natural outgrowth of the objectives and processes that are defined for the project BIM, it is actually a separate set of parameters that need to be explicitly defined. A BIMXP, along with an accompanying set of Level of Design (LOD) parameters and schedule milestones for each portion of the model, can be used for this purpose. Many GCs, CMs, and subcontractors have Virtual Design and Construction (VDC) teams which are highly capable of independently modeling specific areas of the buildings to aid in coordination. Clarifying the modeling requirements of the design team versus those of the GC's team is a step that should not be overlooked.

5. Discuss and Document the Intended Project Use(s) and End Use(s) of the BIM

The BIMXP noted above may also be used to memorialize the true purpose of using BIM for the project, as there are often many. In most cases, BIM is seen as a way to save time, money, or both but that is not always the case. Sometimes BIM use is just a byproduct of the way designers and contractors work while other times the owner is looking for a pre-construction walk-through of the facility to better understand the design before construction, or a detailed model for ongoing facility management use after the project has been completed. In each case, the quality, accuracy, and completeness of the BIM will vary.

6. Establish Accountability for Coordination and Redundancy for Backups

The BIM must be internally coordinated, just as a traditional 2D drawing set is. It must also be coordinated across revisions, modifications, and file versions. Due to the complexity of a 3D model, the potential for costly design rework is high if coordination is not centrally monitored and controlled. And, even though many of the files are now hosted in the cloud, it never hurts to maintain some redundancy in the backups that are maintained locally.

The six mitigative steps summarized above all point to a singular theme – successful use of BIM begins with the end in mind. "Righting the ship" mid-course will require much more effort than simply starting with a clearly defined strategy. The promise of accurate, progressive, efficient, virtually error-free design and construction with BIM may be achievable but it is also elusive. By increasing the knowledge that each stakeholder has as to how BIM will be used in a construction project as well as the challenges that are commonly encountered with those uses, it is possible to maximize the benefits and minimize the challenges. BIM use is inevitable – why not use it in a way that benefits your project?

About the Authors

Christopher Nutter, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, is a Senior Managing Director in the Construction Disputes and Advisory Practice and is a leader of the Professional Liability and Defective Construction Group. With more than 25 years of experience in the design and construction industry, Chris advises clients on commercial, residential, institutional, and government projects, nationally and globally. Chris's work includes technical analyses of design and construction processes and performance for corporations, contractors, developers, municipalities, design firms, and insurers. He has managed and directly performed forensic, consulting, and architectural design services including field assessments and surveys, repair and construction protocols and document production, and building envelope analysis among others. As an expert, Chris has been qualified and has testified at mediation and in U.S. Courts and Arbitration venues. He has offered expert opinions regarding errors and omissions, defective design and construction, building envelope performance, and architectural standard of care. Chris is a registered architect in multiple states, a Member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), certified by the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), and is accredited as a LEED AP BD+C by the United States Green Building Council.

Brian Dance, PE, SE, MBA, is a Senior Director in the Professional Liability and Defective Construction Group of Ankura's Construction Disputes & Advisory Practice. He has more than 17 years of experience in engineering analysis, design, project management, construction claims analysis, and forensic engineering investigations. He currently assists with multi-million-dollar construction disputes for building owners, designers, contractors, insurers, and their counsel, and has broad experience in the construction industry with projects ranging from design and construction administration of high-rise concrete structures to complex steel structures to multi-disciplined industrial plant modifications. He has experience in multi-family housing, municipal, healthcare, aviation, education, and retail facilities throughout the U.S., Canada, and overseas. He has experience in the analysis and design of both public and private buildings, having worked on projects for state and federal governments, including the U.S. Navy on the island of Guam. Moreover, he provides consulting, analysis, and advisory services as well as constructability/peer reviews and façade investigations. Mr. Dance is a licensed Structural Engineer in Illinois and a licensed Professional Engineer in Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and Tennessee. He is also certified as a Project Management Professional with the Project Management Institute and is an NCEES record holder.

References

- "BIM Project Execution Planning Guide" Version 2.0 Draft April 16, 2010, A BuildingSMART alliance project, 126 Pages.

- "Contractors Guide to BIM" Edition One, AGC of America, 2006, 48 pages.

- "Integrated Project Delivery: A Guide," V1, American Institute of Architects, 2007, 62 pages.

- "SmartMarket Brief: BIM Advancements No. 1," Dodge Data & Analytics, 2014, 34 pages.

- "Liability and BIM," AIA Best Practices, John Sieminski November 2007, 3 pages.

- "What is going on with BIM? On the way to 6D," Andrew Chew and Meredith Riley, 13 pages.

- "BIM for Infrastructure: A Vehicle for Business Transformation," Autodesk, 2012, 18 pages.

- "BIM: Mapping out the legal issues," Koko Udom, February, 2012, 13 pages.

- "BIM Tools Matrix," Preliminary Design and Feasibility Tools, 5 pages.

- "BIM Planning for Facility Owners," John Messner, Penn State, 2012, 42 pages.

- "BIM," infoComm International, 2010, 26 pages.

- "Claims, Disputes, and Litigation Involving BIM," Jason M. Dougherty, 2015, 197 pages.

- "BIM from a practical perspective," Jos Mulcahy, Ashurst Australia, 2013, 9 pages.

- "Disputes Resolution: Can BIM help overcome barriers?" Serdar Koc & Samer Skaik, 2013, 15 pages.

- "LACCD Building Information Modeling Standards," Interim Version 2.0, 2009, 30 pages.

- "Managing Integrated Project Delivery," Chuck Thomsen, FAIA, CMAA, 105 pages.

- "BIM Implementation: An Owner's Guide to Getting Started," The Construction Users Roundtable (CURT), April 2010, 48 pages.

- "Level of Development Specification," BIMForum, October, 2015, 195 pages.

- "BIM Guidelines for Design and Construction," Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2015, 145 pages.

- https://learn.aiacontracts.com/articles/6523765-introducing-aia-contract-documents-2022-bim-documents/

- https://www.consensusdocs.org/contract/301-building-information-modeling-bim-addendum/

- Quan T Nguyen et al 2020 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 869 022038

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.