Last year, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) introduced the American business world to a new gateway to determine which entities were to be included in consolidated financial statements – FIN 46. Officially known as FASB Interpretation No. 46 (which, in turn, interprets Accounting Research Bulletin No. 51, Consolidated Financial Statements (ARB 51)), FIN 46 represents a significant change in accounting standards. Because FASB sets the rules that become generally accepted accounting principles – or GAAP – the new rule has a direct impact on every company that needs to keep its books and records, and to report, under GAAP. Because all franchisors must include their audited financial statements within the Uniform Franchise Offering Circular, this standard will impact every franchisor in the U.S., whether publicly or privately held.

Rather than applying rules, FASB attempted through FIN 46 to apply broader accounting principles. The goal, in the case of FIN 46, was to address so-called special purpose entities (SPEs) - entities at the heart of some of the rather notorious corporate scandals of recent years, that had allegedly been used to hide certain losses from the eyes of auditors and investors. FIN 46 applies these accounting principles to require companies to consolidate the financial results of SPEs, now called variable interest entities (VIEs), on to the balance sheets and into the operating and cash flow statements of their sponsoring business enterprises.

The Original Proposal.

As originally adopted by FASB in early 2003, FIN 46 gave accountants a license to apply a complex quantitative and qualitative analysis to business relationships involving equity investment, debt, and contractual ties, to determine who was in charge of a VIE and who was the most likely party to suffer the greatest cumulative losses or realize the most residual gain. FIN 46 was written so broadly that basic contractual relationships – including, most significantly, virtually all franchise arrangements – were drawn into the interpretation.

The potential consequences of FIN 46 as initially adopted posed an accounting nightmare: Franchisors dictating financial statement principles to franchisees; franchisees sharing the most intimate details of their individual businesses with franchisors and their accountants; CEOs and CFOs of public franchisors who are required to provide certifications under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act taking on personal liability for the integrity of the accounting records and internal controls over financial reporting of perhaps thousands of franchised businesses over which neither they nor the public franchisors had responsibility.

Balance sheet impacts mainly include accounts receivable and fixed assets and current and long-term liabilities. If the franchisor sold products to its franchisees, inventories will surely be affected. Even such items as deferred taxes will be touched by consolidation. Line items from the top to the bottom of the operating statement, including critical measuring sticks such as revenue, gross margin, OSG&A, and net operating income, can be affected. Thus, the business relationship currency, the increased costs, and the financial statement impact warranted franchisor attention to FIN 46.

The International Franchise Association staff, assisted by counsel and interested IFA members, took action. Through white papers, comments submitted to FASB, meetings, and hearings they brought the looming crisis to the attention of FASB, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and members of U.S. Congress. The results of this effort were positive. First, a staff interpretation (FSP 46‑8) was issued to officially recognize some of the points that the franchise community made. That interpretation provided a bit of relief. Then, on the morning of December 24, 2003, as a Christmas present to the franchise world and others, FASB issued FIN 46R. For FASB, the R stands for revised. For the franchise world, the R stands for relief. That relief, however, is not complete. While it is less likely that most franchisors will have to consolidate under FIN 46 as revised (FIN 46R) than under the initial draft, under FIN 46R, franchisors and franchisees still did not fully escape the consolidation issue. An analysis is required to determine whether and, if so, how FIN 46R might apply.

How FIN 46R Works

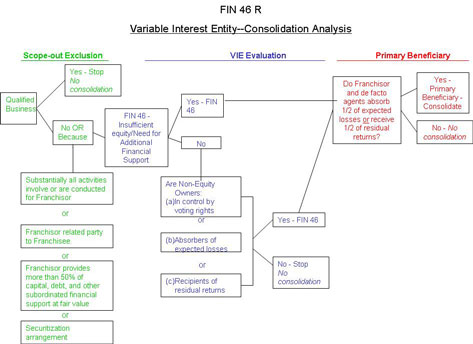

FIN 46R, like many accounting principles, is a matrix of decision points with major yes/no decisions based upon qualitative and quantitative sub-decisions. A diagram of the FIN 46R matrix is presented below.

A. First Hurdle – Business Scope Exclusion

1. Is there a business? As it relates to franchisors, the first decision point is whether or not the franchisee is a "business." This is called the "business scope exclusion." A business is deemed to be a self-sustaining, integrated set of activities and assets conducted and managed for the purpose of providing a return to investors. A business consists of:

(a) inputs – all of the material tangible and intangible assets, capital, and labor needed to make a product or provide a service;

(b) processes – that is, the processes that are applied to those inputs (processes include business systems such as strategic management, operations management, and resource management); and

(c) outputs – in a business, the resulting outputs are used to generate revenue by obtaining customers.

If the franchisee is not a "business" as defined in FIN 46R, then further FIN 46R analysis is required. If the franchisee is a "business," the relationship of the franchisor and franchisee needs to be considered to confidently claim exclusion from FIN 46R.

2. Is the business conducted for the franchisor or reliant upon the franchisor’s subordinated financial support? If the franchisee is a "business," the next questions require a review of the franchisee’s business structure. A franchisor must consider the following questions:

(a) Do substantially all of the franchisee’s activities involve, or are they conducted on behalf of, the franchisor and its related parties?

While an analysis is needed, most franchised businesses are unlikely to fall within the scope of this factor. In private discussions, audit firms have advised us that this relationship will be deemed to exist when there is a "closed loop" system – such as one in which the franchisor controls the franchisee's input and processes, or takes all or most all of the output created by the franchisee. That situation is rare among franchise companies, where inputs may be available from a variety of acceptable sources and where output – in the form of products and services – is typically sold to third-party customers. Dealerships and some distributorship arrangements could have difficulties with this requirement. However, most franchise networks will not involve activity that will fall under this category.

(b) Did the franchisor or its related parties provided more than 50 percent of the total equity, subordinated debt, and other forms of subordinated financial support measured at fair value?

These are the most likely trips over the first hurdle. An analysis requires a look at:

Related Party Equity. Direct or related party economic involvement in franchisees will trigger further analysis under FIN 46R. For this purpose, related parties include franchisor management (and their family members), subsidiaries, sister companies, and parents. If a related party owns a franchisee, the business will be subject to a FIN 46R evaluation. Franchisors that enter into joint ventures to form franchisees need to consider whether their equity involvement will trip the consolidation hurdle. An investment that gives the franchisor or a related party over 50 percent of the franchisee’s total capitalization will bring the franchise under the consolidation rules, as will material subordinated financial support. While joint ventures are not commonplace in domestic franchise arrangements, they are frequently used as a vehicle in international franchise structures. To the extent franchisors are not required to consolidate the results of their joint ventures under other aspects of GAAP, FIN 46R may require that the joint ventures be consolidated.

Subordinated Financial Support. Subordinated financial support is any variable interest, meaning any pecuniary interest in an entity that varies with changes in the value of net assets of the entity (other than the variable interest), that will absorb some or all of the entity’s expected losses. In other words, if a franchisor or a related party is actively involved in the business of a franchisee, has an investment in a franchise, or provides credit enhancement to a franchisee, it can expect to have to step into the FIN 46R evaluation. Subordinated financial support may also include guarantees a franchisor gives on the franchisee’s behalf; the interpretation includes situations where the franchisor will absorb the franchisee’s losses through financing mechanisms such as subleasing real property or leasing equipment to the franchisee.

(c) Is the franchisee’s activity primarily related to securitization, asset-backed financing, or single-lessee leasing arrangements?

This factor is unlikely to apply in a franchise setting.

If the answer is yes to any of these questions, even though the franchisee is a business, the business scope exclusion will not apply and the franchisor must proceed through the FIN 46R matrix. If the answers are no, then the franchisor can wipe its brow, breathe a sigh of relief, and slash its outside accountants’ budget significantly – no further evaluation is necessary.

B. Second Hurdle – VIE Interest

As illustrated in our diagram, at this hurdle all that has been determined is whether franchisees qualify for the business scope exclusion from FIN 46R. Failing to so qualify is not the end of the consolidation-free world – just the start of a deeper analysis. The next step is to determine whether the franchisee has sufficient total equity at risk to carry out its business without additional subordinated financial support. If the answer is yes, the evaluation continues. If the answer is no, then the franchisee is a consolidation candidate.

1. Is there sufficient equity? Total equity at risk includes equity that shares in profits and losses. It excludes equity interests issued in exchange for subordinated interests in other entities (VIE swaps), amounts paid to the equity investor by the franchisee or others, or amounts financed for the equity investor by the franchisee or other persons involved in the franchisee. If the total equity at risk is less than 10 percent of the franchisee’s total assets, the total equity at risk is deemed to be insufficient. However, the inverse is not the case. Rather, for a franchisee with total equity at risk that is greater than 10 percent of its total assets, the franchisor must first consider qualitative factors such as proven financial ability and comparability of equity invested to businesses having similar assets that do not require additional subordinated financial support. Then, if the qualitative tests are not met, a quantitative test that measures total equity to estimated expected losses must be undertaken.

2. Who makes decisions, absorbs losses, and realizes gains? Assuming that the franchisee has cleared the equity sufficiency hurdle, the next evaluation is an analysis of control. Who are the decision makers? Who is obligated to absorb expected losses? Who has the right to receive the expected residual returns? If the answer to any of these questions is anyone other than the equity investor group, the franchisee is a consolidation candidate.

The FASB’s staff provided guidance via an FASB staff position paper, FSP FIN 46R‑3, issued at the same time as FIN 46:

The FASB staff believes it was not the Board’s expectation that all franchise arrangements would be variable interest entities. Rather, the FASB staff believes it was the Board’s expectation that franchise arrangements with equity sufficient to absorb expected losses would normally be designed to provide the equity group (the franchisee) with key decision-making ability to enable it to have a significant impact on the success of the entity (the franchise).

FSP FIN 46R-3 helped to clarify the question of just who is the decision maker. This pronouncement acknowledged the arguments that IFA’s task force had advocated – which were that the decisions relevant to the consolidation question are those that affect day-to-day operations and fundamental matters such as hiring and firing employees and amount and character of capital. The franchisee’s decision to sign a franchise agreement, and therefore adopt and adhere to business standards required by the franchisor designed to protect the assets of a franchisor and all of its franchisees, does not confer upon the franchisor the control needed to transform the franchisor into the "decision maker" and render the franchisee a VIE. (However, FSP FIN 46R-3 also notes that if, as a condition of providing financial support, a franchisor requires that it be given control over the organic decisions of the franchisee, then the franchisor might become the decision maker.)

Relief has also been provided in determining who absorbs what amount of expected losses and who is to receive anticipated residual returns. Expected losses and residual returns are measured on the basis of changes in the fair value of net assets determined by quantifying probable expected cash flows from operations. In other words, the analysis is based on variations from financial projections, not a measurement of actual results. Expected losses can be attributed to equity owners, guarantors, lenders, and others who may suffer from a decline in the value of the net assets of the franchisee. Thus, a franchisor who has no equity interest in a franchisee may be attributed expected losses if the franchisor has provided credit enhancement to the franchisee either alone as part of a group program (such as loan guarantees, lease guarantees, or subleases). Fortunately, it is now clear that customary franchise and license fees payable to the franchisor are not included in the equation.

C. Third Hurdle – Primary Beneficiary

Moving through the matrix, it has now been determined that the franchisee does not qualify for the business scope exclusion and that it is a variable interest entity because it either does not have sufficient equity by FASB standards or someone other than its equity owners has control over day-to-day and fundamental decisions, or shares in expected losses or residual returns. This takes you to the final hurdle of the matrix.

1. Who is the Primary Beneficiary? So, because the franchisor has tripped over a hurdle or two, a franchisee is characterized as a VIE and is a consolidation candidate. There is still one more matrix decision point to be considered – who is the "primary beneficiary?" Every VIE has one (but only one) primary beneficiary. The primary beneficiary is the party that absorbs a majority of a VIE’s anticipated losses, recognizes a majority of the entity’s residual returns, or does both. Only the primary beneficiary is required to consolidate with the VIE. The primary beneficiary can be an equity owner, a lender, a credit enhancer, or a contracting party, depending upon the determinations of expected losses, expected residual returns, and amounts at risk. A de facto agent or two can tip the scales where the interests in the VIE are fractionalized. Because many franchisors have subsidiary and sister companies involved with franchisees and often permit management and employees to invest or otherwise participate in franchisees, the potential for de facto agency combinations can be serious.

2. Is there a de facto agent? A de facto agent of a franchisor is a party that cannot finance its operations without subordinated financial support from the franchisor, e.g., a sister company to the franchisor or another franchisee of which the franchisor is the primary beneficiary. It may also be any person that receives its interest in the franchisee as a contribution or loan from the franchisor, as well as an officer, employee, or director or equivalent of the franchisor. A close service provider to the franchisor, such as a lawyer or accountant, also could be a de facto agent to the franchisor. Finally, a de facto agency could apply if the franchisor can constrain another party’s ability to sell, transfer, or encumber that party’s interest in the franchisee. However, FASB has made it clear that usual and customary franchise agreement transfer restrictions are not included in such determination. The risk of de facto agency is the potential for combining loss absorption and residual return interests of minority parties to create a single de facto principal, the franchisor, who would be deemed the primary beneficiary.

Testing VIE Status

The decision points described above quite significantly narrow the number of franchisee relationships that could constitute VIEs that are consolidated with the franchisor. But what about existing relationships? What about changes in relationships after a franchise relationship has already been established?

For the most part, making a FIN 46R evaluation is a prospective endeavor; that is, the analysis is performed at the time the franchisee begins operations. Franchisee relationships created and that begin operations before December 31, 2003 must be evaluated, but if the franchisor, after making an exhaustive effort, cannot obtain the information necessary (e.g., the franchisee’s financial statements) to determine whether the franchisee is a VIE, or whether the franchisor is a primary beneficiary, or to perform the accounting required to consolidate, then the franchisee will be excluded from being a consolidation candidate. However, fairly extensive financial statement footnote disclosure of the franchisor’s interests in franchisees is required, and continuous efforts to obtain the necessary information must be made.

Once a FIN 46R evaluation is made, the franchisor need not revisit its decision if, for example, the franchisee suffers actual losses that exceed its expectations. Revisiting the decision not to consolidate is only required if the franchisee’s governing documents or contractual arrangements with the franchisor change the character or adequacy of the equity investment at risk, or if there is a return of investment to the equity investors so that other pecuniary interests become exposed to losses. If the franchisee undertakes additional activities or acquires additional assets beyond those anticipated at the inception, reconsideration is required only if the additions increase the franchisee’s expected losses. Finally, a revisit may also be called for if the franchisee takes in additional equity investments or curtails its activities in a way that decreases its expected losses. However, troubled debt restructurings are not intended to warrant a revisit to the FIN 46R evaluation.

Implementation

FIN 46R is applicable to public company that have interests in VIEs or potential VIEs that are SPEs after December 31, 2003. For all other public company purposes (except for small business issuers) FIN 46R considerations apply to financial periods ending after March 15, 2004. Application to small business issuers begins no later than the first reporting period after December 15, 2004. FIN 46R applies to new VIEs of non-public companies created after December 31, 2002. However, a non-public company can defer application of FIN 46R until the beginning of the first annual period beginning after December 15, 2004.

Summary

Franchisors and franchisees cannot ignore FIN 46R. The relief granted by FASB when compared to the original interpretation is helpful and, for the most part, means that most franchise relationships fall into the business scope exclusion or do not trip all of the hurdles leading to consolidation. However, because many franchisors have related party franchisees, make loans to franchisees, provide debt or lease guarantees to franchisees, or sublease to franchisees, franchisors have no choice but to be alert to the decision points that could lead to consolidation considerations.

If consolidations are to occur, it would behoove the franchisor to plan in advance and in its franchise agreements. For example, a franchisor would be well advised – and may have little choice other than – to require that its franchisees provide audited financial statements prepared by an auditor acceptable to the franchisor (in some cases, this may end up being the same audit firm that the franchisor uses), abide by GAAP, and adopt internal controls over financial reporting records.

In short, franchisors are far better off with FIN 46R than with the original version of the standard. But the new standard compels franchisors and franchisees to pay attention to the financial statement implications arising from the structure of their relationships.

This article is intended to provide information on recent legal developments. It should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on specific facts. Pursuant to applicable Rules of Professional Conduct, it may constitute advertising.