Since President Obama formed the Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team ("HEAT") in May 2009, combating health care fraud has been a federal "cabinet-level priority."1 Statistics from fiscal year 2011 ("2011") demonstrate the impact of the federal government's investment of substantial resources in health care enforcement. Last year, federal and state enforcement agencies filed a record number of criminal and civil cases and recovered record-breaking financial settlements in the health care fraud arena.

According to available data, the Department of Justice ("DOJ") initiated 1,235 new health care fraud prosecutions in 2011—an increase of 68.9% over fiscal year 2010 ("2010"),2 and recovered $2.4 billion in health care settlements and judgments under the federal False Claims Act ("FCA").3 In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services' ("HHS") Office of Inspector General ("OIG") reported that 614 criminal and 381 civil actions had been brought against individuals and entities allegedly involved in health-care-related offenses. As a result, HHS obtained $3.6 billion in investigative receivables and $947 million in non-HHS investigative receivables, including receivables relating to States' share of Medicaid restitution.4

The general enforcement trends from last year include:

- Increased number of prosecutions, often involving charges of mail and wire fraud;

- Increased number of cases and substantial recoveries under the FCA, which remains the primary civil enforcement tool;

- Increased collaboration and coordination between enforcement agencies;

- Increased focus on durable medical equipment, home health and cardiac care industries;

- Increased focus on individuals, both for criminal charges and exclusion from federal health care programs; and

- Increased use of publicity to emphasize the seriousness with which the government views health care fraud and abuse.

This advisory reports on 2011 federal health care fraud enforcement and offers a general snapshot of the landscape that sets the stage for health care enforcement as 2012 begins.

Criminal Enforcement Trends

Interagency Collaboration and Coordinated Fraud Takedowns

In 2011, enforcement agencies improved their coordination and effectiveness; they crossed borders and state and federal lines as divisions of DOJ, HHS, U.S. Attorneys' Offices and state law enforcement agencies worked together to open numerous health care fraud investigations, charge more defendants with health care fraud crimes, secure growing numbers of convictions and plea agreements and obtain more money from violators.

One of the results of this increased coordination was that enforcement agencies conducted numerous raids and takedowns in 2011. For example, in February 2011, the Medicare Fraud Strike Force ("Strike Force") announced charges against 110 defendants located in all nine Strike Force cities.5 Collectively, these defendants were charged with defrauding Medicare of over $240 million. In August and September 2011, Strike Force teams executed an eight-city operation that involved the highest total of false Medicare billings in a single takedown in Strike Force history. As a result of this operation, 91 individuals were charged with participating in Medicare fraud schemes that involved approximately $295 million in false billings.

Another case in 2011 resulting in multiple criminal convictions involved a Miami-based mental health care corporation, American Therapeutic Corporation ("ATC "), its management company, Medlink Professional Management Group, Inc. ("Medlink"), and a related company, American Sleep Institute ("ASI") (collectively, the "ATC Defendants"). The Strike Force prosecuted the three owners of the ATC Defendants, as well as 19 individuals, including managers, doctors, therapists, patient brokers and marketers who assisted in submitting fraudulent claims to Medicare. These charges included health care fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy to defraud the United States and to pay and receive kickbacks. After pleading guilty in April 2011, one of the owners was sentenced to 50 years in prison—the longest prison sentence ever imposed in a Strike Force case. ATC and Medlink also entered guilty pleas relating to the conduct at issue. And the now-defunct companies will potentially face more than $80 million in financial penalties.

Using Broader, Non-Health-Care-Related Criminal Statutes

The federal government is increasingly filing charges under broadly worded criminal statutes that are not specific to health care fraud to capture wider ranges of conduct than are covered by the health-care-specific statutes. This charging pattern suggests a strategic decision by the government to charge defendants with crimes that require less evidence of criminal intent or activity to secure a plea or conviction.

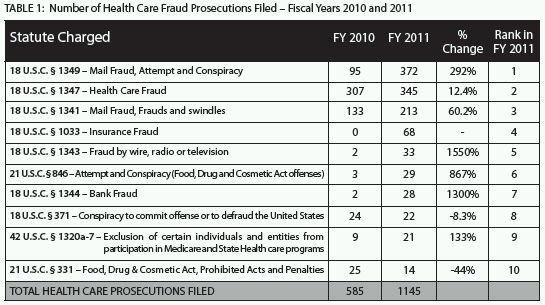

Although the number of criminal cases with a lead charge under the federal Health Care Fraud statute (18 U.S.C. § 1347) historically has been, and continues to be, high, 2011 saw a dramatic increase in the use of the mail and wire fraud statutes, among others, to prosecute health care crimes.6 The mail fraud conspiracy statute was the most common lead charge in criminal health care fraud matters that DOJ filed in 2011;7 federal prosecutors reported 372 such cases, representing a 292% increase from cases charged under the same statute (as the lead charge) in 2010.8 2011 also saw a 1550% increase in the number of cases where wire fraud was the lead charge.9 Table 1 illustrates the range of health-care-fraud-related statutes charged as lead offenses in 2011 as compared to those charged as lead offenses in 2010.

Increased Focus on Specific Industries

Criminal enforcement in 2011 touched many health care industries, including Durable Medical Equipment ("DME") and cardiac devices. The conduct under investigation largely involved allegations of fraudulent overbilling, billing for services not rendered, or billing for medically unnecessary services and the provision of illegal kickbacks paid by these providers to patient recruiters and patients. Law enforcement also focused on physician practices and pharmacies believed to have committed drug-distribution-related violations.

In 2011, enforcement increased dramatically in the DME industry. For example, in April 2011, Rickey Kanter, the former CEO of Dr. Comfort, agreed to a plea and civil settlement with DOJ relating to allegations of Medicare fraud. The government alleged that Dr. Comfort sold shoe inserts that the company falsely marketed and represented as conforming to Medicare's requirements, despite receiving advice to the contrary.10 Mr. Kanter pleaded guilty to one count of mail fraud, was sentenced to one year and one day in federal prison and was ordered to pay a $50,000 fine. Mr. Kanter also sold his interest in Dr. Comfort, paid $27 million to resolve civil claims arising from the investigation, and was excluded from participation in federal health care programs for 15 years.

Investigation into fraud involving the use of cardiac devices also increased significantly in 2011, affecting hospitals, physicians and device manufacturers alike. Illustratively, on July 26, 2011, a federal jury convicted Dr. John R. McLean of six health care fraud offenses relating to the insertion of unnecessary cardiac stents in patients. Dr. McLean submitted insurance claims for the insertion of unnecessary cardiac stents, ordered unnecessary tests and made false entries in patients' medical records. He was sentenced to 97 months in federal prison and was ordered to pay $579,070 in restitution. The hospital where Dr. McLean performed the unnecessary procedures agreed to pay $1.8 million to settle civil allegations that it had violated the FCA because it was aware of Dr. McLean's activities but had failed to take action to prevent them.

Civil Enforcement Trends

The FCA remains the government's most powerful civil enforcement tool. In 2011, it was used to recover funds paid by the government both for services allegedly billed but not provided and for services actually provided and accurately billed, but which allegedly did not comply with an underlying statutory, regulatory, or contractual obligation. DOJ reported recovering $2.8 billion in 2011 settlements and judgments under the FCA's qui tam provisions, which permit whistleblowers to file suits on behalf of the government and to share in the recovery. The largest portion of the 2011 settlement amounts—$2.4 billion—related to federal health care programs.11 And the number of qui tam lawsuits in 2011 that involved the health care industry increased significantly—rising from between 300 and 400 cases per year to 638.12

Pharmaceutical Settlements

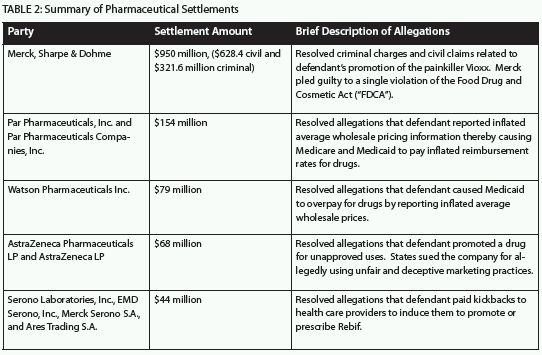

2011 continued the trend of massive settlements in the pharmaceutical industry, as has been the case in recent years (e.g., Pfizer's $2.3 billion settlement in 2009 and GlaxoSmithKline's ("GSK") $750 million settlement in 2010). The largest percentage of the 2011 recoveries from FCA claims stemmed from cases against the pharmaceutical industry. The following chart illustrates some of the largest 2011 pharmaceutical industry settlements:

Settlements in Other Industries

Beyond the eye-popping recoveries in the pharmaceutical industry, there were many other substantial 2011 settlements covering such categories of defendants as: medical device manufacturers; product manufacturers, distributors and suppliers; renal disease providers; home health providers; medical centers; and insurers. The allegations of misconduct varied widely, but included Anti-Kickback Statute violations; Stark Law violations; fraudulent billings; misrepresentation of drug dosages; denial of coverage for care; and the provision of medically unnecessary services. Several large FCA settlements are described below:

In 2011, the government either intervened or filed complaints under the FCA in many ongoing cases. In some, the government filed a complaint even after a qui tam whistleblower had originally filed the lawsuit. For example, in United States ex rel. Conrad v. HealthPoint, Ltd., the United States filed a complaint on behalf of HHS and the Food and Drug Administration ("FDA") alleging that HealthPoint knowingly caused Medicaid and Medicare to pay over $90 million in false prescription claims for a drug called Xenaderm that it marketed as a prescription drug but which was not approved by the FDA and was ineligible for reimbursement. A related case was originally brought by a qui tam whistleblower. By contrast, the government brought the case against Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, listed in the table above, on its own; there was no whistleblower in that case.

A small, but growing, trend has been the proliferation of qui tam suits filed by in-house lawyers, compliance officers, auditors, and others with oversight responsibilities. Just this month, Denver Heath Medical Center paid $6.3 million to settle allegations that it overbilled Medicare and Medicaid by misclassifying patients for hospital admissions. Its former auditor was the whistleblower.

Focus on Individuals

2011 saw a number of individuals saddled with heavy settlement amounts or criminal penalties and, in some cases, excluded from participation in federal health care programs because of their alleged involvement in health care fraud. Individuals targeted for such penalties ranged from single owner/operators of "sham" health care companies established for purposes of committing health care fraud to officers and directors of major Medicare suppliers and other legitimate health care companies. In a recent speech, Assistant Attorney General Tony West announced that the government increasingly will pursue misdemeanor prosecutions under what is known as the Park doctrine (which provides that responsible corporate officers can, in some cases, be held strictly liable for criminal violations of the FDCA).13

2011 also saw overreaching by the government in bringing criminal charges against individuals. Lauren Stevens, an attorney who formerly worked for GSK, was indicted on charges of obstruction of justice and making false statements during an investigation of GSK. In a widely publicized rebuke of the prosecution, the trial judge granted Stevens' Motion for Judgment of Acquittal saying that "...it would be a miscarriage of justice to permit this case to go to the jury."14

The OIG has increasingly used its administrative exclusion authority to bar individuals from participating in federal health care programs. Exclusion pursuant to Section 1128 of the Social Security Act is a collateral consequence of certain criminal convictions. In 2011, the OIG excluded 2,708 individuals and entities from federal health care programs. Although the OIG regularly excludes owners and operators of healthcare entities, it has said that it will now seek to exclude executives from larger companies who oversee, but are not directly involved in, conduct alleged to be fraudulent. This past year, in a well-publicized attempt, the OIG sought, and then abandoned efforts, to exclude the CEO of Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Publicity Tactics

DOJ and OIG have adopted new publicity tactics that appear to be designed to impress upon the general public and members of the health care industry the seriousness with which the government views health care fraud and abuse. Government agencies issued a massive number of press releases to emphasize their enforcement efforts and victories, including a large number of press releases relating to the same individuals or cases. The starkest example of the newer attention-grabbing strategies employed by federal agencies is the OIG's list of "Most Wanted" health care fugitives.15 On its website, the agency posts mug shot-like pictures of individuals who are wanted—or have been captured—for health care fraud and abuse.

Conclusion

In 2011, as it promised, the federal government actively and aggressively pursued conduct involving the health care delivery system that it perceived to be unlawful. We anticipate that health care fraud enforcement efforts will remain a high priority in 2012. As the DOJ has indicated: "We will always seek to disprove the ill-advised notion that health care fraud enforcement is simply the cost of doing business by insisting on judgments, convictions, settlements, penalties, and fines that eliminate any benefit that may be obtained from engaging in unlawful conduct in the first place..." - Assistant Attorney General Tony West, DOJ Civil Division.16

In coming weeks, Mintz Levin will publish additional advisories that will explore some of these topics in greater depth.

Footnotes

1. Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Assistant Attorney General Tony West Speaks at the 12th Annual Pharmaceutical Regulatory and Compliance Congress, (Nov. 2, 2011) (hereafter, "Tony West Speech"). HEAT is an interagency effort led by Attorney General Eric Holder and Secretary of HHS, Kathleen Sebelius, which synergizes the enforcement and prevention efforts of both agencies with respect to health care fraud, by facilitating information-sharing, data-sharing and unprecedented co-ordination and collaboration. Id. Attorney General Holder and Secretary Sebelius created HEAT on May 20, 2009. See OIG Semi-annual Report to Congress, Fall 2011, page III-1.

2. Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse ("TRAC") Report, Record Number of Federal Health Care Fraud Prosecutions Filed in FY 2011, page 1 (hereafter, "TRAC Fraud Report").

3. Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Justice Department Recovers $3 Billion in False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2011, (Dec. 19, 2011).

4. These sums represent expected recoveries resulting from civil and administrative settlements or civil judgments related to Medicare, Medicaid and other Federal, State and private health care programs. OIG Semi-annual Report to Congress, Fall 2011, page III-1.

5. Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Assistant Attorney General Lanny A. Breuer Speaks at the American Health Lawyers Association and Health Care Compliance Association's 2011 Fraud and Compliance Forum, (Sept. 26, 2011). See also OIG Semi-annual Report to Congress, Fall 2011, page III-2. The Strike Force is a key component of HEAT. In 2007, the DOJ's Criminal Division, together with the U.S. Attorney's Office in Miami and the Miami divisions of the FBI and OIG launched the Strike Force to combat fraud and abuse, particularly among durable medical equipment ("DME") suppliers and HIV infusion therapy providers in South Florida. Since 2007, Strike Force teams have spread to nine U.S. cities and continue to co-ordinate law enforcement efforts between federal, state and local law enforcement teams. The nine Strike Force cities are: Miami, Los Angeles, Detroit, Houston, Brooklyn, Baton Rouge, Tampa, Chicago, and Dallas.

6. In the past 10 years, the Health Care Fraud statute (18 U.S.C. § 1347) has ranked #1 as the lead charge in health care fraud cases. TRAC Report, Fraud-Health Care Prosecutions for 2011, Lead Charge: 18 USC 1347 – Health Care Fraud. TRAC compiles its data by filing Freedom of Information Act requests (5 U.S.C. § 552, as amended by Public Law No. 110-175 and Public Law No. 111-83, § 564). The number of prosecutions attributed to each statutory provision only counts the "lead" charge. Thus, the charging documents may allege multiple health care fraud statutes, although the case is only counted once for the lead charge.

7. TRAC Fraud Report, at 4.

8. TR AC Report, Fraud-Health Care Prosecutions for 2011, Lead Charge: 18 USC 1349 – Mail Fraud – Attempt and Conspiracy. See also 18 U.S.C. § 1349, stating "Any person who attempts or conspires to commit any offense under this chapter shall be subject to the same penalties as those prescribed for the offense, the commission of which was the object of the attempt or conspiracy." 9. See TRAC Report, Fraud-Health Care Prosecutions for 2011, Lead Charge: 18 USC § 1343 – Fraud by wire, radio or television.

10. Press Release, United States Attorney's Office, Eastern District of Wisconsin, Rikco International ([d/b/a] Dr. Comfort) and Former CEO Agree to Criminal and Civil Resolution of $27 Million for Health Care Fraud Charges, (Apr. 11, 2011).

11. Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Justice Department Recovers $3 Billion in False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2011, (Dec. 19, 2011).

12. Id.

13. Tony West Speech.

14. United States v. Stevens, No. 8:10-CR-00694-RWT, Tr. at 9 (D. Md. May 10, 2011).

15. OIG Most Wanted Fugitives, available at: http://www.oig.hhs.gov/fraud/fugitives/index.asp.

16. See Tony West Speech.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.