NHS Resolution's recent success in the Lesley Elder case highlights the increasing importance of undertaking investigations where there are genuine questions around exaggeration or fabrication. In this briefing note we examine the options available to a defendant when dishonesty rears its ugly head, and we provide a flow chart which might help solicitors when faced with these issues.

Elder and Atwal: imprisonment for dishonesty

Lesley Elder brought a clinical negligence claim against George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust. Liability was admitted. Ms Elder then sought to recover compensation from the NHS of more than £2.3m. She alleged that the negligence caused her to suffer from severe pain which significantly restricted her mobility and which caused her to require care and assistance.

Sadly, Ms Elder had not been honest. Surveillance evidence showed that she had significantly exaggerated her injuries, the judge noting that without this evidence "... a terrible injustice would have been done to the National Health Service." Contempt of Court proceedings were brought as a result of which Ms Elder was sentenced to five months' imprisonment.

This is now the second time NHS Resolution has been successful in securing imprisonment of those who would seek to defraud the NHS, having demonstrated dishonesty on the part of Sandip Singh Atwal which resulted in a three-month spell of jail time.

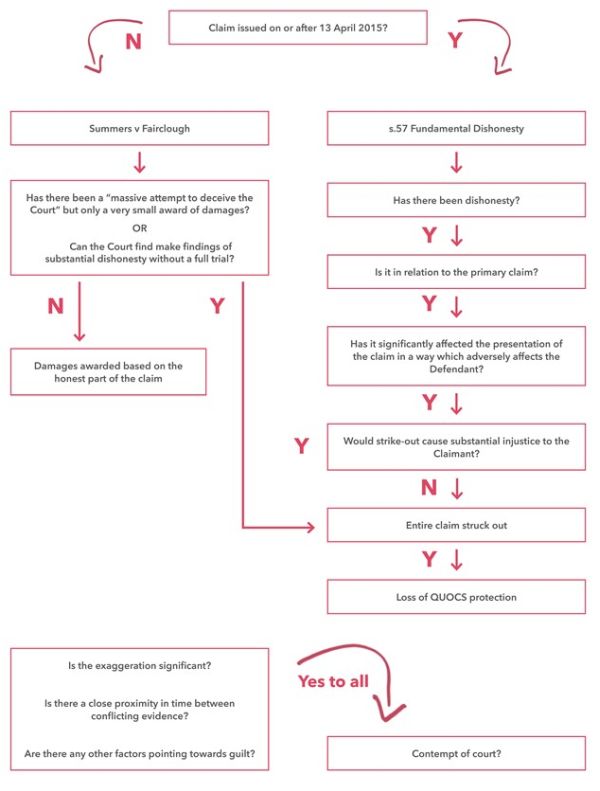

Convictions for contempt of court come at the end of a long process, one which starts in the civil courts. Below we consider the main civil procedural approaches to dealing with dishonesty in compensation claims before going on to look at how and when to pursue contempt proceedings.

Fundamental Dishonesty and s.57

Section 57 of the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 applies to claims issued on or after 13 April 2015. It provides that if a claimant has been fundamentally dishonest in relation to their claim, the claim will be dismissed unless the claimant would suffer substantial injustice.

Has there been dishonesty?

The relevant test is set out in Ivey v Genting Casinos [2017] UKSC 67, as follows: assuming the claimant does not believe their conduct to have been dishonest, then the question whether the conduct was honest or dishonest is to be determined by applying the objective standards of ordinary decent people.

Is the dishonesty "fundamental"?

Adopting the principles set out in LOCOG v Haydn Sinfield [2018] EWHC 51, one must then apply the following tests:

- Has the claimant acted dishonestly in relation to their primary claim? For our purposes, "primary claim" would include the claim for damages.

- Has the dishonesty substantially affected the presentation of the case in a way which potentially adversely affects the defendant? In Sinfield the presentation of a fraudulent claim for gardening expenses in the sum of £14,000.00 was held to satisfy this test.

If these tests are satisfied, the judge must dismiss the entire claim for damages unless the claimant can demonstrate that dismissal of the entire claim would result in substantial injustice to them. As stated in Sinfield "... something more is required than the mere loss of damages to which the claimant is entitled to establish substantial injustice".

To date, the law reports do not provide details of any case where a dishonest claimant has been able to evade s.57 on the grounds of "substantial injustice".

Dishonesty where s.57 does not apply

Section 57 provides a strong remedy for Defendants faced with claims which have been dishonestly exaggerated. However, it will not apply to claims issued before 13 April 2015, or to those (very rare) cases where its application would result in substantial injustice.

Summers v Fairclough Homes Ltd [2012] 1 WLR 2004

The leading common law case where s.57 does not apply is Summers v Fairclough Homes Ltd [2012] 1 WLR 2004, in which the Supreme Court held that, although a Court had the power to strike out a dishonestly exaggerated claim as an abuse of process at any stage in the proceedings, the power to strike out was only to be exercised in very exceptional circumstances. Here the Court was concerned with claims which are partly or substantially dishonest, albeit with a genuine element in the claim.

In Mr Summers' case, the claim was for £850,000 but he only recovered £90,000 at trial, the remainder of his claim being tainted by dishonest exaggeration. Mr Summers' case was not struck out, with Lord Clarke explaining further:

"The draconian step of striking a claim out is always a last resort .... It is very difficult indeed to think of circumstances in which such a conclusion would be proportionate. Such circumstances might, however, include a case where there had been a massive attempt to deceive the court but the award of damages would be very small......However, there is a balance to be struck.... There are many ways in which deterrence can be achieved. They include ensuring that the dishonesty does not increase the award of damages, making orders for costs, reducing interest, proceedings for contempt and criminal proceedings... "

Mr Summers' claim succeeded notwithstanding that he had "persistently maintained his claim on a basis or bases which he knew to be false, both before he was found out and thereafter at the trial". The Supreme Court put the emphasis on Defendants protecting themselves by making Calderbank offers – i.e. making offers to settle the genuine claim plus reasonable costs thereof but at the same time offering to settle the issues of costs on the basis that the Claimant will pay the Defendant's costs incurred in respect of the dishonest aspects of the case.

The decision in Summers might seem to suggest an arbitrary difference in how the courts approach dishonesty, depending on whether the claim was issued before or on/after 13 April 2015. Despite this, the Courts have shown themselves to be increasingly willing to apply the spirit of s.57 to those cases not strictly falling within its remit. For instance, in Admans v Two Saints Ltd (24 June 2016, Swindon County Court) and Matthews v Bupa Care Homes (BNH) Ltd, (15 February 2019, Brighton County Court) the Courts have struck out cases where surveillance footage provides such overwhelming evidence of dishonesty that it would be an abuse of process to allow the claim to continue.

CPR 44 and QOCS

Another area in which dishonesty plays a part is CPR 44.16. In a QOCS case r.44.16(1) provides "Orders for costs made against the claimant may be enforced to the full extent of such order with the permission of the court where the claim is found on the balance of probabilities to be fundamentally dishonest".

The meaning of fundamental dishonesty in CPR r.44.16(1) was considered in Howlett v Davies & Ageas Insurance [2017] EWCA Civ 1696 by the Court of Appeal who approved the approach of HHJ Moloney QC in Gosling v Hailo (29 April 2014) as 'common sense'. The Judge had said:

"... what the rules are doing is distinguishing between two levels of dishonesty: dishonesty in relation to the claim which is not fundamental so as to expose such a claimant to costs liability, and dishonesty which is fundamental, so as to give rise to costs liability

The corollary term to 'fundamental' would be a word with some such meaning as 'incidental' or 'collateral'. Thus, a claimant should not be exposed to costs liability merely because he is shown to have been dishonest as to some collateral matter or perhaps as to some minor, self-contained head of damage...."

In Gosling, the Claimant had suffered a genuine knee injury but, on the very same day that he was attending the experts on his crutches stating that still had knee pain which significantly limited his walking distance, he was filmed walking around shops normally, without sticks. The dishonesty was crucial to about half the claim for general damages and future care (being about half the total claim) and so HHJ Moloney QC had no trouble finding dishonesty fundamental to a sufficiently major part of the claim such that the claimant should be deprived of QOCCs protection.

Dishonesty in practice

Before we conclude by looking at contempt of court, we summarise below how fundamental dishonesty works in practice (click here to download this as a PDF):

Contempt of Court

The ultimate sanction, as demonstrated in Elder and in Atwall, is for a person to be committed for Contempt of Court. This requires one to prove, to the criminal standard, that a claimant has dishonestly and grossly exaggerated their symptoms or has dishonestly fabricated some material evidence.

The contempt process involves a permission stage and a substantive stage. At the permission stage the Judge must find that: (1) there is a strong prima facie case of contempt, (2) is in the public interest to prosecute this, (3) it is proportionate to do so, and (4) it is in accordance with the overriding objective. The latter three criteria allow the Judge to take into account factors other than the claimant's dishonesty, such as personal circumstances, and so before contempt proceedings are pursued an applicant should think about all of the circumstances of the case, and not just the nature of the dishonesty.

Once permission has been granted, substantive proceedings can be pursued. In a clinical negligence context these proceedings are likely to concern actions such as misleading a medical expert on examination as to the extent of their injuries (contempt by interference) or making a false statement verified by a statement of truth in a witness statement (contempt under CPR 32.14(1)). Demonstrating either type of contempt is subject to a strict test. In the case of contempt by interference, the claimant must be shown to have deliberately set out to deceive, intended to interfere with, and in fact, had a tendency to, interfere with the administration of justice. Under CPR 32.14(1) the false statement must have been likely to materially interfere with the course of justice and the maker must both have had no honest belief in the statement, as well as having known of its likelihood to interfere with the course of justice.

Needless to say, to demonstrate all of the elements of the above criteria to the criminal standard of proof requires very clear evidence. Further, the Court has acknowledged that some exaggeration is to be expected, and as Coulson J observed in Kirk v Walton [2009] EWHC 703:

"Exaggeration of a claim is not, without more, automatic proof of contempt of court. What may matter is the degree of exaggeration (the greater the exaggeration, the less likely it is that the maker had an honest belief in the statement verified by the statement of truth) and/or the circumstances in which any exaggeration is made (a statement to an examining doctor may forgivably focus on the worst aspects of the maker's physical condition, whilst it may be less easy to dismiss criticism of a similar statement made when the maker has been repeatedly asked to specify variations in his or her physical condition, and chosen only to give one side – the worst – of the story)."

Often the best evidence of exaggeration or fabrication comes from surveillance evidence, and a defendant must consider the extent of any inconsistency between a claimant's evidence and what the surveillance shows. A minor difference between a statement and surveillance with a long gap of time between the two is far less likely to be a firm foundation for a contempt action than a major difference and a very short gap of time.

This is very much a matter of degree. For instance, a claimant may state in correspondence that they can walk but cannot run but 18 months later surveillance shows them walking briskly. In contrast, another claimant may sign a statement of truth one month saying that they cannot walk, and that same month is shown running during the course of surveillance footage. The former would probably not be a firm foundation for a contempt action, the latter may well be.

Civil law applies stringent sanctions on those who have been fundamentally dishonest in their compensation claims. To an extent this contrasts with what seems to be a more forgiving approach adopted in criminal law, but of course the former is concerned with money, whereas the latter is concerned with liberty. Where contempt of court is demonstrated the claimant who dishonestly exaggerates their claim can expect the most serious of consequences, as Moses LJ emphasised in South Wales Fire and Rescue Service v. Smith [2011] EWHC Civ 1749 Admin:

"Our system of adversarial justice depends upon openness, upon transparency and above all upon honesty. The system is seriously damaged by lying claims. It is in those circumstances that the courts have on numerous occasions sought to emphasise how serious it is for someone to make a false claim, either in relation to liability or in relation to claims for compensation as a result of liability. Those who make such false claims if caught should expect to go to prison...."

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.