2008 was a year that rattled the financial world, but it shook indie film producers as much as anyone. Seemingly overnight, the Big Six's independent ("indie") production imprints, and speciality indie distributors, either shuttered or massively scaled back their operations. Whereas before indie producers might hawk their cinematic wares to the likes of Miramax, Paramount Vantage, New Line, or Sony Pictures Classics, now only a few such organisations remain in existence which specialise in taking quality indie-produced product and finding cinematic releases at any scale.

While Fox Searchlight remains an indie arm for a major studio, the other big names have turned towards a new model when it comes to indie productions — what is called an "output/co-production model" — where studios co-produce smaller-budget films with "mid-major" production houses in order to generate revenue from both a cinematic release and also deals with a television channel like Sky, HBO, Cinemax, etc., who will sign agreements with studios for guaranteed amounts of content or cinematic output.

After the financial crisis, executives became a lot more risk averse, but still offered major benefits to the studios. While they made radically fewer films themselves than they might have done before, the partial outsourcing of production to indie specialist producers allowed them to transfer some risk while still maintaining a decent level of content to sell to the market.

The opportunities afforded to independent film producers by this new model might, at first glance, seem incredibly exciting — quality product produced on smaller budgets but with the distribution arm of a multinational studio giant — but the attractiveness of the opportunity is only matched by its scarcity. Decisions both by the indie houses chosen and the studios themselves are heavily commercially driven. The 20-25 films a year that would come under a typical studio's output deal are assessed on a usual Return on Investment (ROI) basis, but films which would triple their budget might still not be profitable enough to make it onto a large studio's roster of prospective indie projects.

Other than risk mitigation there are other ancillary benefits than just profits for studios still having a role in the indie world. For example, prestige titles that can compete for awards are carrots for artistically-minded talent who need convincing to sign up for a blockbuster about which they might be less passionate. They also generate content beyond the few big budget blockbusters on which the studios spend most of their time and budgets.

Under the co-production model, smaller production houses can share both the financing and the risk, in exchange for a cut of the profits from the output deals. The simplicity of the revenue-sharing model also does away with the need for middlemen between producers and distribution, who often take c.10% commission from gross revenues, as well as the visibility that comes with major studio distribution and relationships. Launches in the US with concomitant television deals also serve to increase the value of the distribution rights outside of the US. The television channels normally ask that each film has a launch on some minimum number of screens and that the studios will spend a certain amount on "print and advertising" (commonly known as "P&A" in the industry), raising awareness of the production overseas.

For indie film-makers, this is a tremendous opportunity. Smaller production houses do not often have access to the worldwide distribution or financial leverage of a big studio and the revenue streams are clear and identifiable (although, P&A costs can also be artificially inflated to capture more of the revenue before it flows back to producers). Having a deal in place with a major studio for a slate of films will attract actors who value the opportunity to work on a creative-led project but also place a high value on knowing that the project will see wide distribution compared to other films at its budget level.

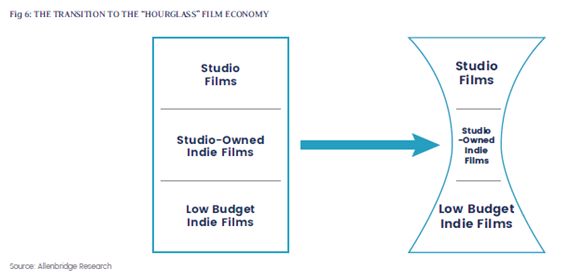

However, the "Big Six" studios do not have limitless capacity. Those independent producers who are the recipients of the commissioning dollars for co-productions are part of an elite group. Since 2008, the "middle class" of filmmakers has disappeared, and film has turned into an hourglass economy (see Figure 6): there are still the rainmakers at the studios with big budgets, there are a few chosen indie film-makers eating the portions given to them from the top table, and there are the huddled masses of indie movie makers shaking the proverbial tin to turn their vision into a reality.

From talking to veteran producers associated with major EIS managers in film production this "new middle class" is clearly where the indie producers raising money today would like to be. It is true to say that some production houses might have a better chance of reaching this status than others: studios are looking to back producers with an artistic vision and credibility with talent. For example, Jason Blum, who has scored a string of successes with lower-budget horror films, from Paranormal Activity to The Purge, and scored critical plaudits with the Oscar-nominated film Whiplash, just saw his production company sign a ten-year first look deal — a first option for the studio to take his company's creative output before he can hawk it to their competitors — with Universal Pictures for a tidy sum.

But investors should be wary of confusing big talk of Hollywood output deals for evidence that this is likely, or even at all possible, for producers working on typical EIS budget levels. Demand in search of supply without screen agent middle men is indeed an exciting business model compared to the "build it and they will come" mentality of collateralised indie filmmaking more typical in the sector. While major co-production deals might be the desired destination, there tends to be a long journey and a string of mega-hits like Mr Blum's before they become a reality.

MJ Hudson Allenbridge's Film and TV Sector Piece is available to download at https://www.mjhudson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Tax-Advantaged-Investing-in-the-UK-Film-and-TV-Industry.pdf

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.