A recent High Court decision confirmed that Big Horn UK Limited (Big Horn) and the company's sole director, Mr Enchev (as joint tortfeasor), had infringed Red Bull's EU trade marks (EUTMs). The court found that Big Horn's signs took unfair advantage of the distinctive character and reputation of the well-known energy drink manufacturer's marks, but were not likely to give rise to confusion on the part of the public. Rather, it was far more likely that the average consumer would perceive the Big Horn products as cheaper or alternative versions of Red Bull's products, which would stimulate sales of Big Horn's products in a way that would not have occurred had the Big Horn signs not so directly brought to mind the visual and conceptual forms of the Red Bull trade marks. The concern was therefore one of free-riding, bringing the infringement within the scope of Article 9(2)(c) of the EU Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR).

Background

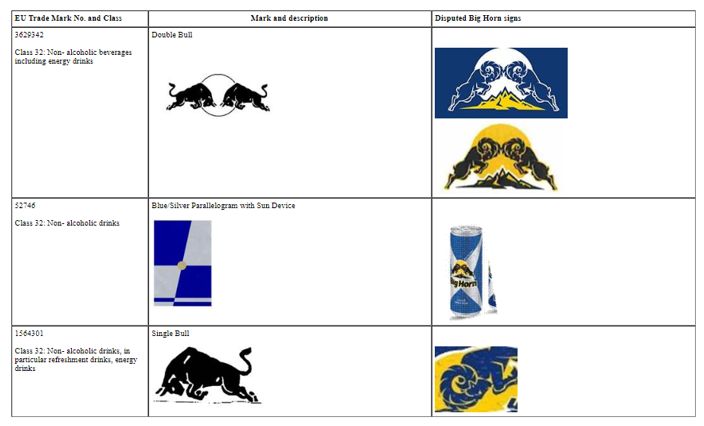

The case concerned the Red Bull marks set out below and the following Big Horn signs:

In August 2016, the second defendant, Voltino (a Bulgarian company, against which judgment was found in October 2019) filed an application for an EU trade mark which featured a double ram and golden sun sign, together with the words "Big Horn" in Class 32 for goods including energy drinks and various types of water. Red Bull became aware of the application in September 2016 and filed an opposition to that trade mark application in November 2016.

During the course of these opposition proceedings, Big Horn drinks appeared in the UK and Bulgaria. Test purchases by Red Bull found that the drinks were being sold in cans of an identical shape and size to classic Red Bull cans, and in addition bearing the mark for which registration was sought, the cans also featured a geometric blue/silver design shown below.

Red Bull's opposition to Voltino's application was initially rejected by the EUIPO Opposition Division in May 2018. However, this decision was overturned on appeal, and Voltino's application was rejected in its entirety on 7 January 2019.

The court considered the following questions:

- Whether, within the meaning of Article 9(2)(b) EUTMR, the Big Horn mark was at least similar to the Red Bull trade marks, was used on similar goods, and gave rise to a likelihood of confusion;

- Whether, within the meaning of Article 9(2)(c) EUTMR, the Big Horn signs were at least similar to the Red Bull marks, giving rise to a link between the sign and the trade marks in the mind of the average consumer, so as to lead to unfair advantage being taken of the distinctive character or reputation of the Red Bull trade marks without due cause; and

- Whether Mr Enchev would be personally liable for any infringement as a joint tortfeasor.

Article 9(2)(c) issues

Similarity

Starting with the Big Horn double ram sign, Bacon QC noted that the EUIPO Board of Appeal had found that there was some similarity between the sign and the Red Bull mark, even if it was low, as the marks "were unlikely to be overlooked by the average consumer". Additionally, both signs consisted of two silhouetted hoofed and horned aggressive animals charging, with their legs in similar positions captured before the moment of impact, and in both cases this was in front of a background of a circle.

The judge concluded that there was visual and conceptual similarity between Big Horn's double ram sign and Red Bull's double bull mark. He also found that there was visual and conceptual similarity in relation to Big Horn's blue and silver geometric device and Red Bull's blue and silver parallelogram device (using approximately the same colour distributions, with angular geometric shapes and central yellow sun element) and Big Horn's single ram and Red Bull's single bull mark.

Link between the signs and the trade marks / unfair advantage

Bacon QC went on to make a global assessment, taking into account a number of factors when considering whether a link could be established between Big Horn's signs and Red Bull's marks (such that use would give an unfair advantage to Big Horn). These factors included the fact that:

- Red Bull trade marks had a global reputation and were highly distinctive,

- Big Horn signs were being used for the same products as Red Bull (energy drinks and water) and these were being sold in the same retail outlets as Red Bull drinks, in identically sized cans; and

- the Defendant's Facebook page included numerous pictures of their cans placed directly next to Red Bull drinks.

The judge concluded that Big Horn's signs were designed so as to "enable Big Horn to free-ride on the reputation of Red Bull", and to benefit from Red Bull's marketing efforts to create a particular image with its trade marks.

Article 9(2)(b) EUTMR

Whilst it was no longer strictly necessary to consider infringement under Article 9(2)(b), Bacon QC made it clear that the Big Horn signs would not have given rise to a likelihood of confusion on the part of the average consumer. Even with a low degree of attention, he considered that an average consumer was likely to be well aware of the differences between the signs and was not likely to consider that a Big Horn product to be a Red Bull product, whether at the point of initial interest (initial interest confusion), at the point of purchasing the product, or observing the product post-sale (post-sale confusion). Instead, he found that the average consumer would likely perceive the Big Horn products as cheaper or alternative versions of Red Bull's products.

Joint tortfeasorship

The court applied the test on joint tortfeasance as set out in Fish & Fish v Sea Shepherd [2015] UKSC 10, which states that a defendant will be liable as a joint tortfeasor if:

- the defendant has acted in a way that assisted the commission of the tort by the primary tortfeasor; and

- the defendant did so pursuant to a common design to do or assist with the acts that constituted the tort.

Mr Enchev's actions were deemed to have fulfilled the test set out in Fish & Fish, as he set up the company for the importation and marketing of Big Horn drinks, controlled advertising via Big Horn's social media accounts, was directly responsible for Big Horn's activities and was the company's controlling mind. It did not make any difference that Voltino made the product, nor that they designed the sign.

Take home points

The judgment highlights:

- the importance of a careful analysis of all factors (including the strength of the mark's reputation, the degree of distinctive character of the mark, the degree of similarity between the marks, and the nature and degree of proximity of the goods or services concerned) when carrying out an assessment of the likelihood of confusion; and

- that it does not necessarily follow that a copycat product will result in a likelihood of confusion.

It is therefore a useful case for brand owners to review when considering challenging the activities of a copycat brand, particularly when free-riding is the issue.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.