Transparency in enforcement

On 27 February 2024, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) published CP24/2: Our Enforcement Guide and publicising enforcement investigations – a new approach, which sets out a proposal that would see the regulator publicly announce the opening and progress of investigations, and other proposed changes to simplify the FCA's Enforcement Guide (EG). A summary of the key areas covered by CP24/2 can be found in our earlier post.

Having now had several opportunities to hear directly from the FCA, and in particular, Therese Chambers, this e-bulletin considers the proposed changes to the FCA's approach, in particular to the early announcement of enforcement investigations, and includes key questions relevant to the proposals in CP24/2 that the FCA has, so far, failed to adequately address.

The FCA has indicated that it welcomes debate on these points, and we will continue to engage with the FCA to scrutinise the proposals and offer constructive alternatives.

The Proposed Approach – in brief

Summary of the proposed approach

The FCA's current approach has been to comment on ongoing investigations only in exceptional circumstances. CP24/2 proposes a radically different approach. The FCA is proposing to publicly announce the opening of an enforcement investigation, updates on the investigation, and (where applicable) the closure of investigations.

Key elements of revised approach are:

- Announcements may include the identity of the subject of its investigation (Investigation Subject), industry sector, regulatory or legal provisions the investigation relates to, and a summary of the suspected breach, failing or other misconduct being investigated.

- Individuals will generally be treated differently because of data protection and privacy laws. In what appears to be in keeping with the FCA's current approach, investigations into individuals will only be announced in exceptional circumstances where it is lawful to do so, and it is in the public interest.

- Any decision whether to announce an investigation and/or to provide a progress update would be taken on a case-by-case basis pursuant to a new public interest framework. We consider the proposed public interest framework (PIF) further below.

The FCA has identified several policy drivers underpinning the revised approach (a number of which are reflected in the PIF):

- Reassuring the public that the FCA is taking appropriate and prompt action;

- Educating and deterring market participants by disseminating information on what the FCA expects and where others might have fallen short;

- Encouraging whistleblowers and witnesses to come forward; and

- Driving FCA accountability in terms of the efficiency and pace of its investigations by putting its investigations in the public spotlight.

The public interest framework

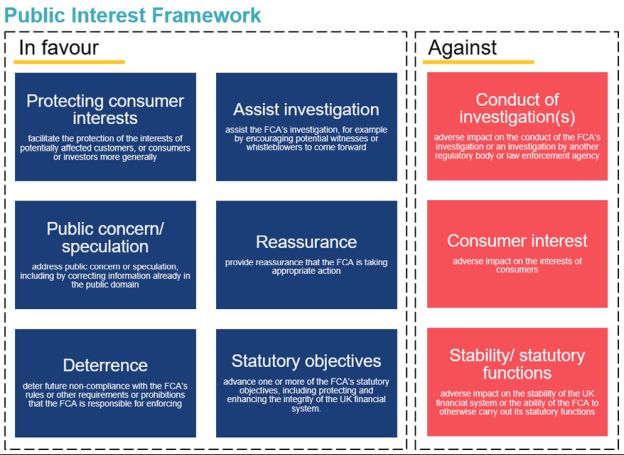

The PIF is the cornerstone of the revised approach. The decision to make an announcement, and, crucially, whether to disclose the identity of the Investigation Subject, will be decided on the basis of the PIF. No presumption in favour of, or against, disclosure is being proposed under the PIF1, although we understand that around 2/3 of current investigations may meet the PIF test.2

Pursuant to the proposed amendments in CP24/2, six factors point to disclosure being in the public interest,3 and three factors point to disclosure being against the public interest.4

The proposed EG 4.1.4(1) makes clear that these factors are non-exhaustive and that the FCA will take all relevant facts and circumstances into account.

Changes to the Enforcement Guide

The FCA's CP also proposes making changes to the EG in the FCA Handbook. EG currently sets out the processes the FCA follows when conducting Enforcement investigations, as well as other related matters. The FCA has said that the current guide is out of line with current FCA practice and is unduly unwieldy. It has therefore proposed cutting the document down substantially, including removing material which repeats legislative provisions, moving certain sections to DEPP and SUP, and putting other material onto an updated version of the Enforcement pages of the FCA's website. The result is a much shorter document, reducing from 328 pages to 59.

The CP states that the FCA does not intend to make wide ranging changes to its processes but does specifically reference a small number of examples where it is making changes. This includes a change which seeks to clarify the FCA's approach to the attendance of a firm's legal advisers at a compelled interview where, depending on the facts of the case, it may "reasonably be assessed" as potentially prejudicing an investigation, for example where there is a conflict of interest between an individual under investigation and the firm, or where the legal adviser owes a duty of disclosure to another person, such as the interviewee's employer.

The FCA has also proposed removing references to preliminary findings letters and preliminary investigation reports as they are no longer used and provides clarification on the basis on which it will accept a firm's own investigation report on a limited waiver of privilege basis. Directors in Enforcement will be able to make decisions to apply to court to commence civil and criminal proceedings, whereas the power was previously reserved to Executive Directors.

The FCA has stated that, as it is not required to have an Enforcement Guide, it will no longer consult when it is changed, albeit it does not expect to make regular or substantive changes in the future. It has said that it will do so when it is required by statute, or it is necessary to do so. The CP has stated that any changes will be published on the FCA's website.

Key questions

- Does the FCA need to make the proposed changes regarding publicity of investigations?

The FCA's CP states that greater publicity of enforcement action will reassure the public that it is taking appropriate and prompt action to address risks to consumers and investors and deter poor conduct. The CP therefore states it will "decrease the likelihood that harm to consumers and markets will occur in the first place... [therefore] increase market confidence and so enhance the stability and integrity of the UK's financial system [and] promote trust in our financial markets". However, the CP does not address why the changes proposed by the CP are necessary to achieve these objectives. Put another way, is the FCA right to conclude (as the CP implies) that these outcomes are currently not being achieved sufficiently because of a lack of publicity around enforcement action?

The FCA may have in mind statistics such as only 41% of adults having confidence in the UK financial services industry as a whole, although consumers have higher levels of trust with their own providers (e.g. 54% of adults with a mortgage had high trust in their own mortgage provider). But these statistics need to be seen relative to others that show a general trend in trust in institutions decreasing over time.

It is also not clear that more and earlier information about FCA enforcement would reassure the public that the FCA is taking appropriate and prompt action. Greater transparency about the number of investigation cases the FCA opens and closes without further action (65% according to the FCA), and the length of time it takes to investigate, may well create a perception of inaction. We note that the number of high-profile failed prosecutions by the SFO (which are public by their nature) in recent years has led to increased criticism and the perception of inefficacy.

That is not to say that there are no circumstances in which the FCA should publish information in relation to enforcement action. For example, where it is necessary to reassure the public about the subject matter of the investigation or to address public concern or speculation in order protect consumer interests. In most cases, these circumstances will apply where at least some details about the subject matter of the investigation are already in the public domain, and the fact that the FCA is commencing an investigation may reassure or help consumers to decide what action they should take in response.

Making an announcement in these (exceptional) circumstances is already possible under the FCA's current approach to exceptionally commenting on ongoing cases. Perhaps some tweaks to existing guidance could help, but are wholesale changes to the existing approach necessary?

- Why have the FCA's views changed from previous consultations?

This is not the first time the FCA (and its predecessor, the Financial Services Authority (FSA)) has looked at how regulators should approach transparency.

In its Discussion Paper (DP) 08/3,5 the FSA set out detailed considerations of how transparency should be used as a regulatory tool. Many of the points raised in DP08/3 are directly relevant to CP24/2. DP08/3 provided analysis of the risks with adopting a "name and shame" approach. In particular, the FSA considered the reasons for due process around the exercise of public censure powers:6

"In short, significant procedural safeguards were specifically built into FSMA in order to prevent the casual, rash or unchallenged use by the regulator of public statements that could damage a financial services firm's reputation and commercial standing. This in turn reflected the lengthy discussion and debate in Parliament during the drafting and passage of FSMA on the balance between the regulator's enforcement and other powers and the rights of the regulated."

Specifically in relation to its approach to commenting on ongoing investigations, the FSA repeatedly acknowledged, in clear terms, the prejudice that might be inflicted on the Investigation Subject.

In CP17, when consulted on its enforcement powers under the then Financial Services and Markets Bill (which would later come into effect as the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 ("FSMA")), the FSA stated "We propose that, as a general policy, the FSA will not make public the fact that it is (or is not) investigating a particular matter. Publication of the fact that an investigation has been commenced by the FSA may prompt unwarranted public concern about the matters and persons within the scope of an investigation. It may put consumers' funds at risk or do unwarranted damage to the reputation of firms, issuers or individuals involved."7

Again in DP08/3, the FSA stated, "We believe there are several significant issues and competing priorities regarding the use of publicity in the enforcement context, particularly where investigations or proceedings are ongoing and there has been no determination of culpability. A balance needs to be struck between various factors, including... concerns about the fairness of publicity by us – and, potentially, consequential media attention – potentially prejudicing those who are the subject of an investigation where the case is ongoing." 8

In helping the market to consider the FCA's proposed changes, it would be beneficial for the FCA to explain why their thinking has moved on from these previous positions. The concerns previously highlighted are as prevalent today as they were in 1998 and 2012, if not more so with the advent of social media and the increased drive towards sensationalist media reporting. While, of course, we live in a different regulatory world now, it's unclear what could have changed to support the proposed about turn in relation to publication.

- How will publicity drive efficiency of investigations?

The CP is equivocal about how publicity will improve the efficiency of the FCA's investigations. The CP notes that an "increase in transparency will make our efficiency and pace more visible" (although no claim that publicity will help achieve these aims) and recognises "the potential for publicity to hamper investigations".

The possibility for publicity to delay investigations is real. For example, the FCA may feel pressure to follow through on the initial breaches it announces (e.g., by pursuing a line of inquiry or proceeding with enforcement action) when it would otherwise have amended the scope of its investigation or opted to not proceed. The proposal also risks Investigation Subjects being less willing to settle claims at Stage One and will perhaps increase the number of cases taken to the Upper Tribunal.

Further, the publicity of investigations may impact the FCA's decision making. Whilst in speeches and discussions about the CP, Therese Chambers has stressed that the FCA will not back away from tough cases, it is hard to see how the complexity of a case will not at least influence the FCA's decision making about what cases to take on or publish they are investigating. With the possibility of public pressure, the FCA may favour taking on or publishing enforcement investigations which it considers will be easier to complete within a reasonable timeframe. If this is linked to the FCA's proposals to streamline its caseload of investigations (which are not expanded upon in the CP), then this should assist with making investigations more efficient by increasing resources available to those streamlined cases the FCA does pursue. But this may not achieve 'impactful deterrence'. On the other hand, more media expectation of the announcement of an investigation may push the FCA to open more investigations, reducing the prospects of speedier enforcement outcomes and 'impactful deterrence'.

- Are the proposed changes the best way to deter poor conduct?

The FCA's premise in the CP is that the "deterrent effect of enforcement action is greater the closer it is to misconduct occurring. The longer it takes for outcomes to be determined, the longer it takes for us to send important signals to the markets we oversee about what we consider serious misconduct to be".

We agree that earlier conclusion of investigations is beneficial – justice delayed is justice denied, and given the length of time it takes the FCA to resolve its cases at present, we can see there is definitely a need for action. But it leaves open the question of whether the FCA's proposed approach is the best way of achieving that aim. It is a missed opportunity that the FCA has not explored other means of disseminating information regarding enforcement action to the market in a timely way. The FCA could describe the conduct in question and its concerns in terms that are non-case specific, while at the same time noting that it has commenced investigations against firms. This could be in a manner similar to other publications such as MarketWatch, "Dear CEO" letters, press releases etc. These forms of communication would be more efficient because they would not need to be subject to the same public interest analysis. They would also be just as effective in terms of educating or deterring market participants, and arguably more so, because the FCA could cover conduct and concerns that are broader than any specific case and include issues that are not the subject of enforcement. As CP24/4 notes, enforcement should not be seen as the only, or best, way of tackling harm. A more general communication to the market could therefore take account of the broader spectrum of regulatory interventions in sending a message to educate and deter the industry more widely.

Other means to achieving this end would make enforcement related press releases more informative, and the FCA's enforcement notices shorter and more accessible to the public.

- Why is potential reputational damage to firms not relevant to the FCA's statutory objectives?

The CP proceeds on the basis that, although a "more transparent approach may raise concerns about potential impact on our investigation subjects", this will not be a specified factor considered by the FCA as part of its public interest analysis as "assessing if publication of an announcement or update is in the public interest should, while taking account of all relevant facts and circumstances, be primarily focused on promoting our statutory objectives".

However, it is not clear why the FCA has concluded that the potential impact on firms is not relevant to its statutory objectives, and why its view on this matter has changed from the previous consultations we set out above.

It is important to recognise that the statutory threshold for opening an investigation under FSMA is very low – there only need to be "circumstances suggesting that a firm or individual may have breached one or more of our rules or principles, or may be guilty of certain offences". In recent years, the FCA has generally sought to open more cases, at an earlier stage. As a stated matter of policy, the previous Director of Enforcement made clear that it was a diagnostic tool, to be used to establish if something had gone wrong, and that it was "a fundamentally different process to litigation where we have a view about what has happened".9 While the new co-Directors of Enforcement have articulated a desire to focus their investigative efforts, the threshold as a matter of law and policy has not been formally changed.

It is not difficult to foresee that the publicity arising out of an FCA announcement may cause severe damage to firms given the low bar both in law and in recent practice. There could be severe financial impacts, including from loss of existing and potential clients, and large volumes of complaints and requests for information. For small and medium sized firms, this may even call into question whether they could continue as a going concern. Even for larger listed firms, in our experience, where regulators have announced investigations, it has had an immediate, significant impact on share price, which is exacerbated by the uncertainty of outcome. This potential for harm has long been recognised by Parliament, the courts, and the regulator itself.

These outcomes are clearly relevant to the FCA's statutory objectives:

- Consumers will be impacted by firms that fail as a result of the harm caused;

- The integrity of the UK financial system will be impacted as firms perceive there to be unfairness in the way that it is regulated; and

- Competition will be impacted as there will be fewer firms and therefore less choice for consumers.

It is also relevant in assessing whether the FCA has had sufficient regard to the regulatory principle set out in s.3B(1)(b) FSMA. This provides that a burden or restriction imposed on a person or activity should be proportionate to the expected benefits. There is clearly an argument that the burden in this case is disproportionate to the (asserted) benefits when having regard to the harm that will be caused. This is especially concerning if, as is the case in 65% of investigations currently, the case is concluded without any finding of breach.

- Does the CP sufficiently consider the potential impact on the UK's international competitiveness?

The FCA has a secondary objective of advancing the international competitiveness of the UK economy and its growth in the medium to long-term. The argument put forward in CP24/2, in simple terms, is a high-level assertion that transparency will improve trust, integrity, cleanliness and the attractiveness of UK markets.

The FCA notes that the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) adopts a similar approach to one being proposed in CP24/2. While MAS's written guidance broadly aligns with the FCA's proposal, a key point of context which CP24/2 does not mention is that in practice, MAS does not ordinarily publicise its investigations. Investigations publicised by MAS have generally concerned cases where the subject matter was already in the public domain.

The FCA does not refer to any other international financial markets. That may well be because the approaches taken in the other major international financial centres by regulators is markedly different – by way of example:

- United States – In general, the Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission do not comment on ongoing investigations and treat them as confidential. In the criminal context, the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure provides that grand jury proceedings are secret, subject only to limited circumstances. Accordingly, the US Department of Justice usually never discloses the existence of an ongoing investigation.

- Europe – European regulators do not generally comment on ongoing investigations. By way of example, the Autorité des marchés financiers in France, Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa in Italy, Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht in Germany, and Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores in Spain, all keep information about ongoing regulatory investigations confidential pursuant to (variously) legislative or constitutional requirements and established practice, save for in exceptional circumstances; and

- Hong Kong – the Securities and Futures Commission and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority are bound by secrecy requirements (respectively contained in section 378 of the Securities and Futures Ordinance and section 120 of the Banking Ordinance) to keep information about ongoing investigations confidential.

The potential impact on Investigation Subjects, and the approach of regulators in other jurisdictions, is clearly relevant to assessing the competitiveness of the UK markets. A perception that firms can, as a matter of routine, be subjected to potentially unfounded (given, per the FCA, that 65% of investigations do not result in enforcement) reputational damage through the publication of information about investigations, seems likely to discourage firms from choosing to operate in the UK when other financial regulators do not adopt the same approach. This is a particular concern given other headwinds which the UK faces as an attractive place for international financial services firms to do business.

- Why are the safeguards and due process otherwise available to firms not replicated here?

Specific safeguards were enshrined in FSMA by Parliament which recognised the harm and unfairness that a regulator could inflict with its enforcement power. When exercising its power to publish information about a warning notice under section 391(1)(c) FSMA,10 the FCA must follow due process set out in section 391 FSMA and the EG. In particular, FSMA provides that one of the grounds that would prevent the FCA from publishing such information would be if it is unfair to the Investigation Subject.11 When publishing a public censure, the FCA must follow due process as set out in sections 207 and 208 FSMA and the EG.

The potential impact from a publication announcing the commencement of an investigation, a statement about a warning notice, and a public censure, are likely to be very similar in practice. In fact, a statement about an ongoing investigation is potentially more damaging because of the uncertainty it carries. And yet, with the proposal, there is the perverse outcome that those who the FCA has found to be in breach are afforded significantly more protection than those still under investigation where no breach has been established.

This is because, in contrast with the safeguards and due process reflected in FSMA, the FCA has laid out effectively no due process or safeguards by which the Investigation Subject can object to publication of information about the investigation.

Given the potential impact on firms, the FCA's proposals to address them are not sufficient:

- First, the FCA say they will have regard to all facts and circumstances of the case, and this has been stressed by Therese Chambers in recent discussions of the CP as a safeguard to the potential impact on firms. However, it is not clear how this will work in practice in light of how the FCA interprets its objectives and the public interest. In particular, as the potential impact on the Investigation Subject has not been included as a specified factor in the PIF, the FCA's consideration of the facts is designed to not consider the impact of publicity on the firm; and

- Second, the FCA will include a boiler plate statement that it has not reached any conclusions, made any findings or determined the appropriate enforcement action. Notwithstanding the inclusion of such a statement, for the reasons set out above, the harm (including the reputational damage) of an investigation being announced is inevitable, particularly given the way in such matters are reported in the media. This is to some extent recognised by the FCA because the proposed guidance addresses the fact that the announcement may be "potentially market sensitive".

CP24/2 provides that the FCA will give the Investigation Subject "such advance notice as it considers appropriate. The FCA will usually give no more than 1 business day's notice but may give no notice if it considers that the circumstances require urgency". It is currently unclear what information the FCA will provide to the Investigation Subject when giving advance notice, and whether this would include a draft of the announcement, and reasons why the FCA considers publication to be in the public interest. It is also unclear what process the FCA will adopt to consider any representations made by Investigation Subjects and who the decision maker will be. Given the difficulty that firms settling with the FCA have in seeking to align a press release to the agreed Final Notice, and the recent criticisms of the FCA's practices in its press releases by the Upper Tribunal, a lack of appropriate safeguards is a particular concern.

Also, this proposed approach fails to recognise the practical constraints that may prevent firms being able to properly consider and respond to the proposed announcement with appropriate governance. Where the announcement may be price sensitive, firms would get even less notice, being informed after market close with the announcement to be published at 7am. Such a short timeframe is unlikely to give sufficient time for firms to outline, and the FCA consider, the potential impact on firms. In circumstances where the impact may be severe, and it appears that this is not being properly considered by the FCA, firms may consider they have little choice but to seek urgent injunctive relief. It would be unfortunate if the FCA's proposals lead to such an unintended outcome, as this would clearly be counter to the aims of the FCA.

The potential impact on firms cannot be fully addressed by the FCA publishing an announcement that it has closed its investigation without taking action, and/or by amending the original announcement.

Our view is that the FCA's proposal would effectively circumvent the safeguards enshrined in FSMA and override the clear intent of the legislature. If Parliament thought due process and safeguards were necessary for statements about warning notices and public censures, then it follows that they are at least, and potentially even more necessary in respect of announcements about ongoing investigations that are at an earlier stage of the enforcement process.

- How will the FCA navigate around legal restrictions relating to Confidential Information?

The FCA has expressly acknowledged that it will need to comply with section 348 of FSMA and this is reflected in its proposed guidance. 12

It is unclear whether section 348 FSMA may apply to information contained in an announcement (in particular, the summary of the suspected breach, failing or other misconduct under investigation, or progress updates), such that the FCA would need to rely on a gateway exception (the most likely being the self-help gateway).13

If the FCA does not include details of the misconduct or failures (which is likely to be subject to section 348 FSMA), it is doubtful that its announcement will have any deterrent or educational effect, calling into question the benefit of any such announcement.

The FCA should clarify whether it envisages including information that would require it to rely on the gateway exceptions and explain how those exceptions might apply.

- Does the new Enforcement Guide and the FCA's stated approach align to the stated aim of transparency?

The FCA has substantially rewritten the EG such that identifying all the differences between the existing version and the proposed new one is difficult. It is apparent when conducting a side-by-side assessment, that a number of parts have been removed from the EG which were not specifically signposted in the CP, including the requirement for a legal review to be conducted by an FCA lawyer who had not advised on the case prior to referral to the RDC (existing EG2.14), which was introduced in 2005 as part of the wide-ranging changes to FSA Enforcement following the Legal & General case.

There are a number of other provisions which appear to have been removed, including the requirement that the Chair of the RDC approve any press release in which the RDC was the decision maker, unless the matter goes to Tribunal (existing EG 6.4).

While we understand the intention is to have the whole process reflected at a high level on the FCA's updated Enforcement webpages in due course, there is no indication as to what this will look like in the CP. While some of these matters may relate to internal FCA processes, transparency of the process is an important safeguard for those under investigation, and the legal review in particular was introduced for good reason in the past.

The proposal that legal advisers for firms may not be allowed to attend interviews where the FCA perceives there to be a conflict of interest fails to acknowledge that legal advisers are already subject to their own professional obligations in this respect. The change in emphasis could see more firms being shut out of interviews with their own employees than is currently the case, and seems to echo similar concerns about the (over)protection of a firm's interests by external counsel which Therese Chambers raised in her inaugural speech as co-Director of Enforcement in June last year. In our view, the mere fact that a lawyer owes a duty to the employer would not constitute a valid reason to refuse attendance, or prejudice an investigation. A firm under investigation would be significantly disadvantaged if it only found out what its employees had said when transcripts were disclosed either because the FCA seeks to rely on them in Stage One negotiations, or in the context of Upper Tribunal proceedings. It would add a not insubstantial cost and administrative burden to arrange independent legal advisers for employees, if this became necessary. Similarly, a subtle change to the language around the requirement for a Scoping Meeting at the outset of an investigation to be only on a "case-by-case" basis looks to address the fact that for more sophisticated firms they can be less useful, but it does also suggest that there will be less transparency for investigation subjects than there is at the moment. The FCA could improve this proposal by noting that investigation subjects will always be able to request that a scoping meeting takes place.

On the continued theme of transparency, the CP proposes that Private Warnings are done away with, in the interests of having public enforcement outcomes. It seems that this is an example of the changes catching up with practice, as Freedom of Information Act request data suggests that Private Warnings have not been used by the FCA since 2016. It is not clear however that alternatives, such as Supervisory letters to individual firms, provide any greater transparency of FCA thinking to the market generally. Greater transparency is welcome and, as noted above, could be achieved through industry wide communications of general themes, such as a proposed MarketWatch equivalent, "EnforcementWatch".

An overarching concern is that in a move to simplify the very lengthy EG, the FCA risks losing some of the important guidance and safeguards that are currently in the EG, and those subject to investigation have no assurance that they will all make their way onto the FCA's website or how they will operate in practice. At present, the FCA's Enforcement webpages are light on content and do not have a proper form of user friendly version control or archiving which is present in the Handbook, even if the FCA has stated it will publish when it makes changes. When combined with the stated approach of not routinely consulting on changes in future, it may be that the FCA's processes become less transparent to those who are subject to Enforcement investigations. While the intention of this part of the CP seems to be a genuine attempt to simplify the document without making radical changes, there is a risk that future leadership of the Enforcement division will seek to use these structural changes to further loosen procedural safeguards, particularly if it comes under further pressure to produce outcomes more quickly once it starts announcing the opening of more investigations.

Responding to the CP

We will be responding to the CP and welcome all further views and input on these important matters.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.