Carey Olsen partner William Grace discusses the issuing of Jersey's first-ever financial penalty against a regulated business

In July 2019, the Jersey Financial Services Commission (JFSC) imposed its first financial penalty in the sum of £381,010. Civil penalties were introduced to Jersey in 2015, but the imposition of the first penalty makes it timely to look at the Jersey system and, more broadly, at civil penalties.

Jersey legislation refers to 'financial penalties', but a variety of terms are used in other jurisdictions. Colloquially, Jersey refers to them as 'civil penalties', reflecting the fact that they are not part of the criminal process; there is no charge, no conviction, they are not fines and the court is not involved unless a party appeals.

Jersey's first case

Jersey's first-ever financial penalty was against a listed and well-regarded financial services business for a failure to rectify a codes of practice breach. In summary, several compliance issues were identified in 2014/15 and, despite considerable work, they were not rectified to the satisfaction of the JFSC. The business and its board then addressed all outstanding issues and showed a high level of cooperation; but this was only enough to reduce the penalty, not avoid it.

When undertaking remediation exercises, the JFSC set out expectations for the board of registered persons to ensure the following:

- Tasks are completed and verified to ensure they meet requisite standards.

- The governance structure results in clear accountability and provides transparency, in respect of those areas of the business that require investment.

- The operational structure is organised in a way that enables it to embed procedures and assess compliance therewith.

- Risk and compliance functions are adequately funded and resourced, and the effectiveness of these functions is closely monitored.

- Adequate systems and controls are in place to identify and report risks.

- Staff receive relevant training and promote a culture of compliance within the business.

- Control functions remain appropriate for the scale and nature of the business.

Rationale

There are a number of reasons why civil penalties are used:

- As a deterrent or signalling tool to create positive change.

- To encourage prompt and consistent notification and remediation.

- As an extra regulatory enforcement tool (less draconian than closure/banning).

- As a flexible enforcement tool, with fine-tuning for proportionality and circumstances.

- To mitigate good business paying for bad business.

- To match the powers of other similar regulators and meet the expectations of international standard-setters.

- To create a broad non-conviction-based sanction.

Specifically, Jersey's 2009 International Monetary Fund (IMF) assessment referred to targeting profitability as well as reputation and the Financial Action Task Force's 17th recommendation requires civil penalties for compliant status.

Summary of Jersey's civil penalty system

The JFSC has a discretionary power to impose a financial penalty on a registered person (for conduct after March 2015) or principal person (for conduct after October 2018) in relation to significant and material contraventions of its codes of practice.

The penalty can be up to £4 million against a registered person and £400,000 against a principal person, determined by which of the four bands, outlined below, the contravention falls into and all other relevant circumstances. The penalty will almost always be accompanied by a public statement and must be paid by the party it is imposed on.

The scheme applies to those regulated by the JFSC for conduct of business. It does not apply to those only regulated for anti-money laundering (AML) and certain insurance businesses are also excluded. The scope comprises codes of practice applicable to conduct of business and the JFSC Handbook for the Prevention and Detection of Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism for Regulated Financial Services Business. The scheme did not create new compliance obligations; it merely created a regulatory enforcement remedy.

The penalty must be paid by the party it is imposed on; it cannot be paid by insurance, indemnification or a third party. One can insure surrounding risk, just not the penalty.

Banding and maxima

Jersey's scheme has four bands based on relevant income. This is best understood as a smoothed measure of turnover.

Band 1 – Two failures to notify required matters in a two-year period. This is not about the underlying issue but the failure to have notified an event. Maximum 4 per cent relevant income to a maximum of £10,000 (business or individual).

Band 2 – Failure to remediate contravention adequately or on time. This can be seen as failing to take a second chance. Maximum 6 per cent relevant income to a maximum of £4 million (business) or £200,000 (individual). This was the Band used in the first financial penalty.

Band 2A – Negligent commission of very serious contravention. Maximum 7 per cent relevant income to a maximum of £4 million (business) or £300,000 (individual).

Band 3 – Intentional or reckless commission of very serious contravention. Maximum 8 per cent relevant income to a maximum of £4 million (business) or £400,000 (individual).

The banding prescribes detailed criteria for very serious contraventions (e.g. the business risked jeopardising the need to counter financial crime).

Computation methodology

A complex statutory methodology scheme has been published but the following example gives an idea of how the scheme works.

Imagine that a Jersey business with a relevant income of £10 million commits a Band 2 penalty that is categorised as being at the least serious end of that Band. The starting point is, in effect: relevant income for band x maximum percentage of relevant income for Band x weighting for seriousness (the scale starting at 15 per cent). This equates to £10 million x 6 per cent x 15 per cent = £90,000.

A number of aggravating and mitigating factors are then added. Say we end up at £100,000; there is then a significant discount of 50 per cent for settlement at the first stage, so the final penalty in our example could be £50,000.

Due process

Penalties will either by imposed by the JFSC either after a hearing or by way of settlement. Rights of appeal exist to the Royal Court of Jersey, which can set aside penalties on the relatively narrow ground of unreasonableness. Settlement discounts are time-sensitive but are in addition to self-reporting discounts. There is a large incentive to self-report and settle.

Extension of civil penalties to principal persons from October 2018

The extended scheme applies to directors of in scope businesses and 10 per cent (or more) shareholders but not to those only holding statutory compliance offices.

There are various reasons to extend civil penalties to individuals, including the fact that behavioural change is more likely when a consequence falls on an individual and it might be appropriate in situations where a business has insufficient or no funds. The principal person regime is, arguably, also the most important plank in Jersey regulation and it was always intended as a next step in the civil penalty regime.

nteraction of the business and individual schemes

A civil penalty can be imposed on a business without imposing one on an individual, but not vice versa. Similarly, the civil penalty regime for individuals requires an individual to be personally culpable in the business' contravention. It is not based on a contravention by an individual of any obligation on them. In addition, the JFSC can impose a civil penalty on one principal person but there is no need to impose a penalty on whole board, while a civil penalty imposed on a business is not enforceable jointly and severally against shareholders or directors.

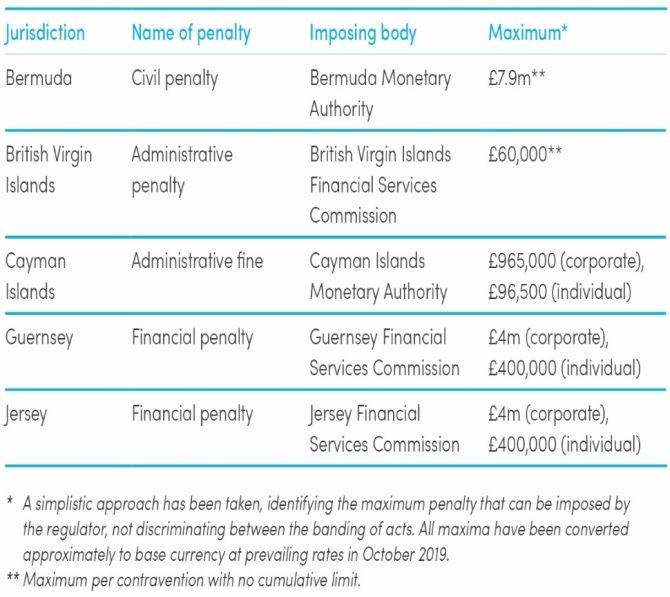

Chart of civil penalties in five leading offshore jurisdictions

Conclusion

Businesses in all well-regulated jurisdictions should expect those regulations to operate in the context of the risk of civil penalties. However, a sense of proportion must be kept. Remember that civil penalties were introduced to create a flexible enforcement tool, with fine-tuning for proportionality, and not for conduct at the extreme ends of the spectrum of seriousness.

In many cases in Jersey, the publicity of an inevitable accompanying public statement may be more of a punishment than the civil penalty. Going forward, we expect to see much more frequent use of civil penalties in Jersey.

An original version of this article was published by the STEP Journal, February 2020.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.