This article was originally published by International Law Office.

Introduction

Interim measures (IMs) are an important tool designed to deal with imminent danger to competition, preserve market conditions during antitrust investigations and improve the overall effectiveness of competition law enforcement.1 To this end, IMs can prohibit certain conduct such as tying or bundling, or require other conduct, such as a compulsory licence, before a competition authority reaches a final decision on the merits of a competition case – hence "interim". The underlying objective of these interventions is to allow a competition authority to intervene before there is too much of a distortion on the market, before (too much) harm is caused. Due to the often-lengthy nature of competition investigations, the principle of being able to act in an "interim" way can be useful for an authority and beneficial to complainants, market players and consumers, but it risks imposing significant burdens on the business in question. The recent decision by the French Competition Authority (the authority) to impose IMs on Meta2 provides a chance to lift the lid on the use of IMs in France, as well as the opportunity to consider what might be seen in this space going forward.

Background

The authority can only order IMs if the practice in question is likely to:

- amount to an anti-competitive practice, demonstrated by sufficiently convincing evidence;3 and

- causes serious and immediate damage to the general economy, or to the sector concerned, or to the interests of consumers, or to the complaining undertaking.4

Such measures may include the suspension of the practice as well as an injunction to behave differently going forward or to go back to the situation prior to the commencement of the practice under investigation. Furthermore, IMs should be strictly limited to what is necessary to deal with the emergency pending a decision on the merits of a competition case.5 Compared with other competition agencies, the authority has been relatively active in this area, issuing more than 30 IM decisions since the 2000s with the general trend averaging just over one IM case per year.6 Looking at the past 15 years, since 2008, the authority has ordered IMs in 11 cases. Of these 11:

- six have led to commitment decisions (ie, about half);

- three have led to a full infringement decision with penalties;

- one claim has been rejected on the merits; and

- the authority imposed a sanction for non-compliance with injunctions in one case.

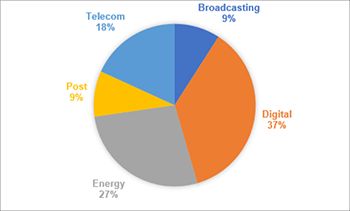

These cases have been mainly in regulated or digital sectors, as the diagram below shows.

Figure 1: Case types

In 2020, the authority estimated that it takes an average of six months to carry out an IM investigation.7 Since 2016, only three decisions imposing IMs have been adopted by the authority, all of them regarding the digital sector. Recent IM decisions of the authority are much more detailed than past ones, and the authority now seems to pay closer attention to the precise legal test for IMs than in some of the older cases.

Facts

In May 2023, the authority issued IMs against Meta for alleged abusive discrimination in its ad verification criteria. The trigger for this latest investigation was a complaint on the merits together with a request to order IMs, brought by Adloox, a small provider of online ad verification services to advertisers and media agencies, against Meta. Online ad verification is a service related to online advertising. It constitutes the technical procedures of quality control of an inventory (the spaces made available by the owner of a website to display ads) or of an impression (display of an ad on a given support). It allows advertisers to verify that their advertising budget has been well spent.8 Specifically, these services include:

- "viewability" measures, which involve verifying that an ad is actually seen by an Internet user; and

- "brand" measures, which are intended to ensure:

- that an ad is not displayed in an environment likely to harm the brand values and interests (brand safety); or

- that an ad is displayed in an environment that best suits them (brand suitability).

These verification services are offered by integrated ad platforms on their own advertising inventories (such as Meta) and by specialised independent operators (such as Adloox), which offer more precise and granular measurements. Independent verifiers need access to integrated ad platforms to fairly compete with them. In its recent decision, the authority alleged that Meta is likely to hold a dominant position in the French non-search online advertising market and that it is perceived as a key partner by all independent verifiers. As a result, the authority found two potential abuses of this seemingly dominant position:

- Meta did not have transparent, objective, non-discriminatory and proportionate access criteria for its "viewability" and "brand safety" partnerships; and

- Meta's refusal to integrate Adloox among its partners could result in a discriminatory practice.

The authority took the view that these practices could cause serious and immediate damage to the independent ad verification industry, freezing the oligopolistic structure of the market and establishing artificial barriers to entry and expansion. According to the authority, these practices are even more serious given the EU Digital Markets Act (DMA)9 that will compel the main ad platforms to give free access to the data necessary for any independent ad verification service. The authority's decision is "innovative" in terms of the frequent and often extensive references to the DMA, despite it not yet having entered fully into force. Indeed, the authority emphasises that its decision to impose IMs in these circumstances is fully in line with the objectives of the DMA. The authority also deemed Meta's online ad verification practices to be harmful to the interests of Adloox, which recorded significant losses whilst its integrated competitors experienced strong growth. According to the authority, Meta's refusal to integrate Adloox could lead to its exclusion from the market by the end of the case investigation, hence the "urgent" need for IMs. Compared to the authority's previous IM decisions in the digital sector, the analysis relating to the criteria to impose IMs is much more developed with regard to, in particular, the causal link between the alleged damage and Meta's practices.

Decision

In the light of the above, the authority ordered Meta to:

- define and make publicly available new access criteria in respect of its partnerships which are transparent, objective, non-discriminatory and proportionate, as well as providing a transparent procedure for assessing these access requests that cannot be by invitation-only;

- grant Adloox rapid admittance to these partnerships, provided the company meets the new access criteria; and

- provide it with regular reports on the measures implemented.

The practices concerned in this case echo those of other major digital players which have also been criticised by the authority over the past few years10, as they involve an accusation of discrimination and require greater transparency of access criteria by way of IMs. However, in this case the authority seems to go further than previous cases. For example, in respect of the first measure, the authority orders Meta to establish "new criteria" using a specific selection procedure that must include an "appeal mechanism". The second measure also goes quite far in terms of access arrangements and requires a notable promptness on Meta's part. The authority nevertheless seems to be imposing one consistent measure on digital players, namely requiring them to provide regular and detailed reports on the implementation of the IMs. In this vein, it is worth recalling that in 2021, the authority sanctioned a company for non-compliance with IMs.11

Key to the imposition of IMs in this case is the context of opening up of the online independent advertising verification sector. To this end, the authority ruled that, far from contributing to the objective of opening up the advertising verification market, Meta's practices restrict the number of independent verifiers active on its platform, and therefore contradict the objectives pursued by the DMA. Consequently, according to the authority, the harm caused by these practices is particularly serious, and justifies the introduction of IMs.12 As the authority is clearly anticipating the DMA coming into effect, it seems to be taking the liberty of going further in the measures imposed in this case, compared with previous cases. These references to and reliance on the DMA, are discussed further below.

Comment

The authority is not alone in making (infrequent) use of IMs. In Europe, they have only been employed in a handful of cases.13 There were suggestions that with the IMs imposed by the Commission on Broadcom in 201914, there may be a revival of this tool, but recent cases have not borne this out.15

In the meantime before the ex-ante DMA kicks in and becomes the default tool for regulating the behaviour of large online platforms16, it is interesting to note that the authority has been prepared to impose IMs on Meta during a time when the regulatory backdrop is shifting. It shows that it remains active despite the changes soon to be implemented in the regulation of big digital players.

Looking ahead

The recent Meta case confirms the authority's interest both in the digital sector and in IMs. Reflecting on how these both play out and interact is particularly interesting. Despite their name, in practice IMs are not so interim – neither in terms of how long they apply for, nor in terms of their reversibility. Indeed, concerns have been expressed that IM decisions in practice end up deciding the full case without the full analysis and protection of rights of the defence.17 In cases where the conduct is ultimately found to be procompetitive, IMs may in fact harm competition albeit for a limited period, if reversible. That said, in some cases, IMs may be much needed to put a swift end to seriously damaging practices, and crucial for businesses who would otherwise have to wait too long for justice to be done.

The importance of a nimble IM regime for deterrence purposes should also not be forgotten. Given the nimbler and ex ante digital rules waiting in the wings it will be interesting to see how competition authorities make use of IMs going forward in digital cases. Reading the authority's decision to impose IMs in this case, it goes to considerable effort to satisfy itself that it is in line with precedents in the digital sector and says that it considers that the conditions required in French law to impose IMs are fulfilled.18 However, it seems that the authority is in fact grounding its decision on the DMA which, as it acknowledges, is not fully effective. If the underlying competition policy objectives pursued by the authority are clear, the approach is innovative from a legal standpoint and somewhat surprising.

A slowdown in the imposition of IMs on the biggest digital players once the DMA has become fully effective can be anticipated, partially due to DMA enforcement falling largely to the EU Commission (which to date has shown itself wary of IMs), and partially due to the ex-ante approach of the DMA which seeks to regulate behaviour in advance, thereby reducing the need to have recourse to IMs in the light of allegedly harmful behaviour.19 Nonetheless, IMs will still be relevant in digital cases falling outside the scope of the new rules (eg, abuses of dominant position) and in other non-digital sectors. In the absence of the limitation of the scope of behaviour which might be classified as abusive under article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, it is quite possible that new forms of abuse, such as the General Court's characterisation of self-preferencing in earlier caselaw, may be identified in the digital sector.

Another route for authorities to go down is that of accepting commitments, which can not only secure significant changes to the way players operate, but also effectively bring a case to an end relatively quickly subject to monitoring and are less likely to be challenged in the courts. In this respect, it may be noted that very recently the UK CMA has issued a Notice of intention to accept commitments offered by Meta on its use of data obtained through digital display advertising.20

This may fuel arguments based on the principle of proportionality, challenging the "necessity" of IMs in these types of cases. At a time when competition authorities are grappling with ever changing business models and consumer behaviour, companies would be well advised to remain alert to all potentially potent tools competition authorities have shown themselves willing to wield and consider using these different options to their advantage.

Footnotes

1. Interim Measures in Antitrust Investigations (oecd.org).

2. French Competition Authority 4 May 2023, Décision n° 23-MC-01 relative à une demande de mesures conservatoires de la société Adloox.

3. Court of Cassation, 8 November 2005, Neuf Télécom, n° 04-16857; Court of Cassation, 9 October 2012, Euro Power Technology, n° 10- 28718.

4. Article L. 464-1 of the French code of Commerce.

5. Ibid. These requirements are similar to those of other competition authorities but in each jurisdiction, it is important to note subtle differences which might be quite significant in practice.

6. French Competition Authority, Annual Report 2020, page 32. Note that under French law, serious damage to a competitor can suffice, but in the EU under article 9 of Regulation 1/2003, the test is serious harm to competition. This difference in the applicable test might explain, to some extent, the more frequent French use.

7. Ibid. At EU level, even longer – see the Broadcom case below.

8. The authority previously looked into this market. See 16 June 2022, Décision No. 22-D-12 relative à des pratiques mises en Suvre dans le secteur de la publicité sur internet.

9. Article 6(8) of Regulation 2022/1925 of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act).

10. See for example: French Competition Authority, 9 April 2020, Décision No. 20-MC-01 relative à des demandes de mesures conservatoires présentées par le Syndicat des éditeurs de la presse magazine, l'Alliance de la presse d'information générale e.a. et l'Agence France-Presse; French Competition Authority, 31 January 2019, Décision No. 19-MC-01 relative à une demande de mesures conservatoires de la société Amadeus; and French Competition Authority, 9 September 2015, Décision No. 15-D-13 du 9 septembre 2015 relative à une demande de mesures conservatoires de la société Gibmedia.

11. Decision 21-D-17 dated 12 July 2021.

12. See paragraphs 252 to 255 of the authority's decision.

13. See for example Case T-184/01 R.

14. EU Commission imposed interim measures on Broadcom (Europa.eu). Note that in this case, the IMs followed a one-year investigation.

15. Interim measures in antitrust cases, should not be confused with interim measure imposed in the mergers context. Nevertheless, IMs in EU merger cases are also rare. See: the Commission's Illumina and Grail merger investigation; Mergers: Commission adopts interim measures (europa.eu); and the ongoing discussions about reviving IMs at EU level with the reform of Regulation 1/2003.

16. See Keynote speech of Mr. Thierry Breton, Commissioner for Internal Market, European Commission at the Commission's Legal Service Annual Conference of 17 March 2023.

17. See comments of Deputy Director for Antitrust and Competition at DG Comp, Linsey McCullum: Years of Regulation 1/2003 conference (europa.eu).

18. See conditions set out above in section 2.

19. Although note that the Commission can impose IMs under the DMA – article 24.

20. CMA, Notice of intention to accept commitments offered by Meta on its use of data obtained through digital display advertising, Case AT 51013, 26 May 2023.

Originally published 13 June 2023

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global services provider comprising associated legal practices that are separate entities, including Mayer Brown LLP (Illinois, USA), Mayer Brown International LLP (England & Wales), Mayer Brown (a Hong Kong partnership) and Tauil & Chequer Advogados (a Brazilian law partnership) and non-legal service providers, which provide consultancy services (collectively, the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are established in various jurisdictions and may be a legal person or a partnership. PK Wong & Nair LLC ("PKWN") is the constituent Singapore law practice of our licensed joint law venture in Singapore, Mayer Brown PK Wong & Nair Pte. Ltd. Details of the individual Mayer Brown Practices and PKWN can be found in the Legal Notices section of our website. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of Mayer Brown.

© Copyright 2023. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.