China has banned all Japanese seafood imports in response to the release of treated water from Tokyo Electric Power's Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station into the sea. As China and Hong Kong, which absorb more than 30% of Japanese agricultural, forestry, and fishery exports, have toughened restrictions on such Japanese imports, seafood prices in Japan have been impacted already.

The hardline policy of banning all seafood imports from Japan in order to halt the release of treated water is regarded as a unilateral economic action or economic coercion to achieve a specific policy objective or demand. Is economic coercion permitted under international law? How should Japan address this?

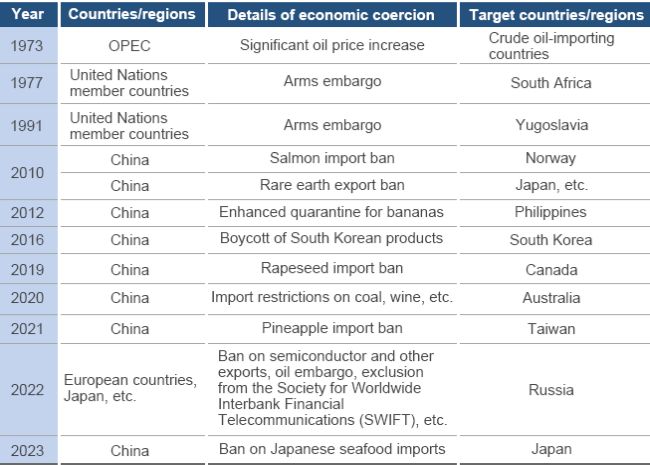

China is not the only country that engages in economic coercion (see table). As early as October 1973, Middle Eastern oil-producing countries unilaterally raised oil prices through the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) on the occasion of the fourth Middle East war in protest of pro-Israel countries. An arms embargo, which was imposed on South Africa for its enhanced apartheid discrimination policy in 1977 in line with a United Nations Security Council resolution, can also be interpreted as economic coercion.

Cases of economic coercion

Economic sanctions imposed by Western countries including Japan against Russia for its recent invasion of Ukraine are also economic coercion to achieve the goal of stopping the Russian invasion. However, all of these economic coercion measures were conducted as collective actions by multiple countries.

In contrast, China has recently repeated economic coercion on its own. China banned salmon imports from Norway in protest against the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to Chinese democracy activist Liu Xiaobo, suspended rare earth exports to Japan over a bilateral territorial dispute over the Senkaku Islands, and restricted Australian coal and wine imports over investigations into the cause of COVID-19. There are also many other economic coercion cases involving China.

The lawfulness of economic coercion measures under international law varies depending on the policy purposes and types of measures. The arms embargo on South Africa was compatible with international law, because the embargo was implemented against the apartheid measures which had been identified by the U.N. Security Council as violations of international law. Economic sanctions against Russia for its invasion violating international law are likewise compatible with international law. However, China's unilateral economic coercion is implemented to counter foreign policies or measures that China opposes. Chinese economic coercion cannot be interpreted as compatible with international law.

As Chinese economic coercion measures include bans on rare earth exports to and seafood imports from Japan and other external trade restrictions, the question is whether these measures are compatible with the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement or free trade agreements to which Japan and China are parties.

China has described the ban on Japanese seafood imports as a measure to protect the lives and health of its citizens from seafood contaminated with the radioactive substance tritium. What China has references here is the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement) to protect the lives or health of people, animals and plants.

The WTO SPS Agreement requires import restrictions for food safety (1) to be based on scientific grounds and evidence, (2) to conform to or at least be based on international standards set by the international organizations, or (3) to be based on risk assessments if tougher standards than international ones are adopted for such restrictions.

The World Health Organization's (WHO) guidelines for drinking water quality set an international standard for the allowable amount of tritium at 10,000 becquerels per liter. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has tested the tritium content of treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station and found that the treated water is diluted before the release to reduce the tritium content to less than 1,500 becquerels per liter, about one-seventh of the above standard. Therefore, the current Chinese ban on Japanese seafood imports amounts to a tougher measure than appropriate for the above third requirement under the WTO SPS Agreement.

In this case, China is required to demonstrate that the measure is implemented on the basis of risk assessments and that the measure is based on scientific grounds and evidence. However, China has not explained that the measure meets these requirements. Therefore, the Chinese measure is a violation of the WTO SPS Agreement.

In addition, China has failed to regulate treated water from its own nuclear power plants, which emit up to 6.5 times more tritium annually than the treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. China thus is requiring more stringent regulations on Japanese nuclear power plants than the levels actually being documented on Chinese ones, running counter to the principle of national treatment.

China's ban on all seafood imports from Japan violates the WTO SPS Agreement. The Japanese government should resort to a WTO dispute settlement procedure to lead China to withdraw the import ban.

Regarding the WTO dispute settlement procedure, the Appellate Body has been inactive since December 2019 as a result of the United States' boycott of the appointment and reappointment of Appellate Body members. Therefore, a party to a dispute that loses its case at the dispute settlement panel stage in the first instance can essentially postpone the case indefinitely by appealing the panel ruling, which will bring the case to the inactive Appellate Body. However, some WTO members, such as the European Union, have established the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) to replace the Appellate Body. China and Japan have joined the MPIA. As such, if Japan wins a case against China at the dispute settlement panel stage, the case cannot be postponed indefinitely.

Japan lost a petition against South Korea's ban on seafood imports from Japan as a response to the Fukushima accident in 2019, as the Appellate Body reversed a dispute settlement panel ruling that had endorsed the petition. This experience might have made the Japanese government more hesitant to file a petition with the WTO against the Chinese measure. Since claims of relevant parties and applicable SPS Agreement provisions differ between the Chinese and South Korean cases, it is too early for the Japanese government to predict a loss in the case against China.

Even if Japan files a petition with the WTO against the Chinese measure, however, several years may pass before the case is finally resolved. Japan should continue to persistently urge China to rescind their measure while bringing the case to the WTO. To this end, Japan should consider at least two routes in addressing the issue.

The first route is to raise the Chinese measure as a "Specific Trade Concern (STC)" for consideration at the WTO SPS Committee. A large number of import restriction measures have been raised as STCs at the Committee. The adequacy of such measures has been examined at the Committee, with the participation of third countries, leading to the withdrawal of many such measures.

The second is the utilization of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in East Asia, to which Japan and China are parties. Regarding risk assessments for SPS import restriction measures, the RCEP agreement requires importer countries that impose such measures to report on the progress of risk analysis at the request of relevant exporter countries. Based on the RCEP agreement, the Japanese government should consider requesting that China conduct a risk assessment as a prerequisite for the measure and to report progress in the assessment in order to exert diplomatic pressure on China to withdraw the measure.

China's ban on seafood imports from Japan in response to the release of treated water, which meets tougher safety standards than international standards, amounts to an illegal, unwarranted economic coercion measure that runs counter to WTO rules. The Japanese government should exert pressure on China to withdraw the ban through the WTO dispute settlement procedure and softer, parallel channels. It is best for Japan to take a resolute approach to illegal, unjustifiable economic coercion.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

Originally Published by The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.