Most people who regularly work with digital devices have already used AI applications to generate output - for example, a title for a blog post. In order for the AI application to be able to do this, the underlying model must be trained in advance with large amounts of data which often include copyrighted content. In this post no. 10 of our AI blog series, we examine the question of whether copyright-protected works may be used to train AI models, what the consequences are if a copyright-protected work is still recognizable in the output generated by an AI application and who - the provider or the user - is responsible.

The current debate on AI and copyright

AI applications generate a lot of new content, but also require an enormous amount of content input to do so. From a copyright perspective, the following key questions arise:

- Can copyrighted works be used to train AI models and generate output without the explicit consent of the owner of the rights?

- How do we deal with the situation where an existing copyrighted work is recognizable in a work generated by an AI application?

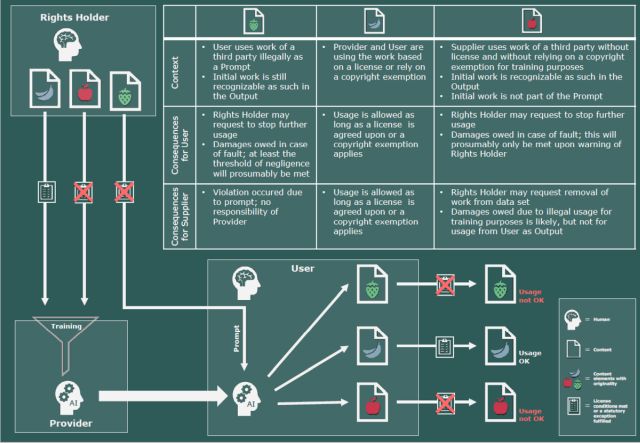

As new legal questions arise in this context and the contractual and technical setup can be complex, it is often not possible to give a blanket answer to these questions. In practice, it is therefore necessary to assess which parties bear which copyright risk when dealing with AI applications. To do this, the roles and responsibilities of the parties involved must be identified and delineated. Once these have been defined, the corresponding actions must be placed in the copyright context. Our analysis is limited to Swiss law.

The key points in brief

- A distinction must be made between the responsibility of providers and users of AI applications.

- Providers may only use copyright-protected content from third parties for the training of AI models if they have an (implicit) license or can rely on an exception provision of copyright law. The exception for personal use can be particularly helpful if copies of works that are not commercially available are used, as is the case with much content that is freely available on the Internet. The exception for scientific research may permit use without the author's consent in the context of academic and commercial research.

- The use of publicly accessible content may be covered by the implicit consent of the rights holder if the rights holder does not provide any restrictions (e.g. terms of use, etc.) and it is not clear from the context that the use is limited to the mere consumption of the content. This implicit consent can only be relied upon until the rights holder makes an explicit statement in this regard (e.g. a warning letter).

- In principle, Swiss copyright law does not apply to training by foreign providers who train their AI models abroad - unless the output provoked by the user infringes the copyright of a third party under Swiss law. Copyright shopping for the training of AI models is therefore possible in principle. The EU has put a stop to this with the AI Act, under which the rules of EU copyright law must be observed even if the training takes place outside the EU.

- Users normally cannot claim copyright to content ("outputs") generated with the help of AI applications.

- AI-output may infringe the copyright of third parties. As long as the user only uses the output internally (internal personal use), there is often no copyright infringement. However, if the user makes the output, which falls within the scope of protection of a copyrighted work, accessible to third parties, copyright infringement must be assumed - even if the user has no knowledge of the infringement.

- As long as the user has no knowledge of the copyright infringement and would not have been expected to recognize it, his primary risk is that a copyright holder can demand that he stops using the work (negatory claims). Claims for damages only come into question in the event of culpability, i.e. when at least the user knew or should have known that the copyright of a third party was being infringed by their output or its specific use.

Roles in the use of AI applications

Most people who regularly work with digital devices have already used AI, for example to write e-mails or other texts, as a translator, to create images or films or even a piece of music. The AI application is told what to do by means of a written command (known as a prompt), e.g. "Create a short, concise title on the subject of AI and copyright". The result, if suitable, is then adopted by the user as the title for a blog post.

In order for AI applications to be able to generate such outputs at all, the underlying model must be trained in advance. In most cases, this is done with a large amount of training data in which the AI model recognizes patterns. The AI application then generates an output based on these patterns and the prompts. In an abstract sense, there are therefore two different roles: That of the user, who uses an AI application for their own purposes, and that of the provider, who trains the AI model and operates the AI application, i.e. ultimately makes it available to the user.

For the purposes of this blog post, the term provider encompasses the party that decides on the functionality and the input or the type of input collection, excluding the prompts used by the user. This means that, in this post, the term provider covers all those who develop and train the AI model and make the AI application available for use, as if they were one person. In contrast, a user is any person who uses the already functioning AI application provided by a third party (the provider) for their own purposes and provokes outputs from the AI application through prompts.

This distinction alone makes it clear that further differentiation will be necessary in practice in order to determine responsibilities in specific cases: The development and training of the AI model and the operation and provision of the AI application will not usually be carried out by one and the same legal entity or natural person. On the user side, the role can also be distributed across several stations, e.g. if a company purchases an AI model for its own use and makes an AI application available to employees. It is also conceivable that supply and use are carried out by the same person, e.g. if an AI application is developed and used for internal process optimization.

Copyright framework for providers of AI applications

Providers of AI applications must train the model on which they are based in such a way that the expected result can be generated when prompted by the user. The quality and quantity of the training data are of crucial importance here. It is not uncommon for text or image material available on the internet to be used. Scraping or crawling software, which automatically collects content from the web, is often used to obtain the largest possible amount of data. However, data from other sources that was not originally created for the purpose of training AI models (e.g. a company's document management system) can also be very interesting for training AI. If this content is protected by copyright, the question arises as to whether its use for the training of AI applications is permissible (this question is also examined in detail in the recently published essay by Sandra Marmy-Brändli and Isabelle Oehri, "Das Training künstlicher Intelligenz" in "sic! 2023").

The provisions of copyright law are relatively strict in this respect: the creator has the exclusive right to determine whether, when and how the work is used (Art. 10 para. 1 CopA; so-called "exclusive right"). This includes in particular the right of reproduction (Art. 10 para. 2 (a) CopA). This includes the creation of physical and digital copies

For the training of AI models, the collected training data is usually stored and the work therewith reproduced. Therefore, if the provider wants to use copyrighted content legally for the training of its AI model (which is usually not seen as "enjoyment of work"), it must be able to rely on a legal exception or the consent of the rights holder (so-called license).

Swiss copyright law restricts the exclusive right in certain areas by means of so-called exception provisions in order to take account of the interests of the general public, e.g. when there is an overriding interest in being able to use works for scientific and educational purposes, or that works may be used for personal use. This is why, for example, anyone is free to copy book chapters or entire books for their own private use.

The exceptions vary, but they all have in common that they allow use without the creator's consent. Certain exceptions allow the user - within the scope of the exception - to dispose of the work freely and free of charge (e.g. the private personal use just mentioned). Others permit use without the creator's consent but not without payment (statutory license), restrict only the exercise of rights but not the actual content of the copyright (collective exploitation) or virtually oblige the rights holder to grant a license (compulsory license).

In the context of the training of AI models, we believe that the following exceptions are particularly relevant: (i) the exception for internal use, (ii) the exception for temporary reproductions and (iii) the scientific research exception.

The internal use exception (Art. 19 Para. 1 (c) CopA) permits the reproduction of copies of works in companies for internal information or documentation purposes, whereby these reproductions may also be made by third parties (so-called "statutory license"). However, the reproduction right is subject to significant restrictions, e.g. the exception does not cover the (largely) complete reproduction of commercially available copies of works (Art. 19 para. 3 (c) CopA). Furthermore, although reproduction is permitted within the scope described, it is subject to a remuneration obligation in accordance with GT 8 (remuneration for the lawful distribution and the making available of works in administrations and companies).

The exception covering internal business use no longer covers the training of AI models if the training and thus the reproduction of the content is not (only) for the internal information or documentation (this refers to the collection, storage and transfer of knowledge within the same organization). The extent of this internal purpose has not been conclusively clarified. With a strict reading, this internal purpose is already exceeded if the AI model is trained with the intention of offering the application for use outside of one's own organization, because this brings the commercial aspect to the fore. This can be countered by the fact that any internal use also fulfills a certain commercial purpose. Even if content is initially used to inform and educate employees, it is regularly intended to have (at least) a positive influence on business operations. If the employees of a law firm are provided with relevant specialist knowledge in the form of excerpts from academic literature, this is generally not done for private pleasure or for filing purposes, but to keep the employees up to date and thus enable them to provide competent and rapid advice to clients. Employees analyze and process the information they receive in order to generate a corresponding output. Similar to what AI does.

The exception covering internal use is certainly no longer applicable at the latest where the work copied for training purposes is found in the output of the AI application and this output (e.g. the work) is made available to persons outside the organization - i.e. can be perceived as such by persons outside the organization. In this case, the reproduction process relevant under copyright law clearly no longer serves the purpose of internal information and documentation, but rather serves directly to provide output to a third party.

In order for works in digital form to be used at all, (intermediate) storage is often required, e.g. in the main memory. In order to make this possible without the creator's consent, the exception for temporary reproductions (Art. 24a CopA) was introduced. This permits (i) a transient or incidental reproduction if it (ii) constitutes an integral and essential part of a technological process (iii) serves exclusively to enable a transmission in a network between third parties by an intermediary or for lawful use of the work; and (iv) has no independent economic significance.

The storage of the collected training data is generally neither transient nor . The storage will also not regularly serve the sole purpose of transmission. The independent economic significance of the use for the training of AI applications exists at the latest when the exploitation of the copyrighted work is impaired by the offering of the AI applications and the resulting facilitation of a certain output.

In our opinion, in many cases, Art. 24a CopA in its current version does not permit the use of copyrighted works for training purposes.

The scientific exception (Art. 24d CopA) permits the reproduction of works for the purpose of scientific research free of charge. Subsequent storage for backup and archiving purposes is also permitted. However, other uses are not covered by the exception. The scientific exception is intended to facilitate the automated evaluation of data. It applies if the reproduction is required by the application of a technical procedure, i.e. if the reproduction is actually necessary in order to be able to carry out a certain technical procedure. A further prerequisite is that lawful access to the relevant works is created. This is the case for works that are made freely available on the internet by the owner, as well as for properly borrowed or purchased works (as long as they are not pirated copies). The main purpose of the reproduction must be scientific research. According to the dispatch on the amendment of the Copyright Act of November 22, 2017, p. 628, this means "the systematic search for new knowledge within various scientific disciplines and across their boundaries". Commercial research is also covered by the limitation.

Reproduction as part of the training of an AI model is conditional on a technical process and legal access is also given for many contents. Therefore, it does not seem impossible that individual providers of AI applications can rely on this barrier, e.g. if the underlying model automatically evaluates or analyzes the stored data for research purposes. However, the situation is likely to be different if the content is only stored for training the AI model with the aim of improving the performance of the application or generating (primarily commercially) usable content for the user. The scientific exception can therefore cover reproduction by the provider in certain cases.

The exception provisions only allow the use of copyrighted works for the training of AI models without the consent of the creator in certain cases; they therefore do not grant a blank check under copyright law.

If a provider cannot invoke an exception provision, he is dependent on the creator's consent. In practice, creators often give their consent to the use of their work by means of a written license agreement; however, this is not mandatory. The applicable copyright law has no formal requirements in this respect, i.e. the creator can in principle also give implied or implicit consent.

Implicit consent is particularly relevant for the use of freely accessible content on the internet. Anyone who makes content available on the internet today will expect it to be consumed and, to a certain extent, used by third parties.

Implicit consent can be assumed if the creator makes the work available online for use (and not just mere consumption) without expressly mentioning this. If, on the other hand, copyright notices are attached or if there is a prohibition of use beyond consumption in the general terms and conditions or the terms of use, implicit consent is out of the question.

Relying on the creator's implicit consent is possible, for example, if the AI application that was trained with these works fulfills the same purpose as the publication of the works on the internet by the creator. In the case of documents that generally serve to inform the public, such as information brochures from public authorities or NGOs, this is likely to be the case, for example; the AI application merely creates a greater reach for this information - the interests of the rights holder and the trainer of the AI model are aligned in this case. The situation is different if the creator makes their works public with the aim of exploiting them directly or, in a second step, commercially in the same way as is intended with the AI application.

Furthermore, implicit consent can only ever be assumed until the rights holder makes an explicit statement to this effect. If a work is used on the basis of implicit consent and the rights holder makes it clear that they do not consent to this use, such use must cease.

The reliance on the creator's implicit consent is therefore not a panacea due to its great dependence on the individual case, but will become increasingly relevant in practice for content without significant commercial value.

If a creator discovers that their work has been used for training by an AI model without their consent, they can take civil action against the provider. For example, they can demand that the infringement ceases or no longer takes place in the future (so-called negatory claims). The rights holder can demand the removal of their work from the training data set completely independently of the output (whether he can also demand the deletion of the model is another question, because for this it would have to be shown that the work as such is still contained in the model and is used as such).If the copyright infringement was negligent or intentional, additional claims for damages and satisfaction can be made (so-called reparatory claims).

In the case of intent, criminal prosecution is also possible. Only those who commit the act "with knowledge and intent" are liable to prosecution. If the infringement is carried out commercially, copyright infringements are not only prosecuted on application, but ex officio. Providers of AI applications are therefore well advised not to deliberately and systematically infringe the copyrights of third parties. This can be accomplished, for example, by implementing appropriate internal guidelines.

Copyright protection for the output of AI applications?

Independent of the question of which works may be used for the training of AI models by the provider, it is relevant for users of AI applications to determine which of their own rights and risks arise from a copyright perspective if the user creates content using AI applications. It must first be clarified whether the user can exclude third parties from using the work, i.e. whether they can assert a copyright to the content.

Copyright protection is granted to intellectual creations of literature and art that have an individual character. The criterion of intellectual creation will regularly be lacking in the case of works created by AI, as the content is not produced by the creativity of a human being, but by an analytical, purely technical process. At best, this criterion could be fulfilled if an AI application is understood as an aid in the sense of a tool for achieving the result, i.e. it only serves to implement the specifications made by a human being, similar to a photo camera. Although such a use of AI applications does not seem to be absolutely impossible, it will only occur very rarely. In order for the output to be attributed to the creativity of the user (and not the AI), the creative content of the output must be included in the prompt. Such use as a mere tool would only be conceivable in the case of e.g. translation tools if the user feeds in a text they have written themselves and then has it translated.

The possibility of granting copyright to the AI itself appears to have been ruled out, at least under Swiss law, due to the criterion of intellectual creation. Even the people who developed the AI will not have such a concrete influence to the extent that authorship of the output can be attributed to them.

Content generated by AI is therefore not protected by copyright under the current legal situation in Switzerland, unless the output reflects the intellectual creation of the user's prompt. This means that users of AI applications have no means of preventing the use of the same content by a third party, at least from a copyright perspective.

Can users of AI applications infringe third-party copyright

In practice, more important than the question of whether the output of an AI application is protected by copyright is the question of the extent to which the generation or use of AI-generated content infringes the copyrights of third parties.

The creator of a work may, subject to the exception provisions, determine whether, when and how the work may be used. In particular, the creator may prohibit the creation of a second-hand work. A second-hand work is a work in which the individuality of the original work is still recognizable.

Since the training data is probably not copied again through the use of an AI application (as such data is not contained in the model itself), the copyright risk of a user is primarily limited to the case that an original work is still recognizable in the output of the AI application. However, this risk exists regardless of whether the work was created by humans or generated by AI applications. Any copyright infringements committed during the training of the AI model cannot be attributed to the user.

While in the case of copyright infringement through the training of AI models, the circle of possible responsible parties can usually be clearly defined (it is the provider), in the case of the unauthorized use of output, in addition to the user (as the main offender), the provider can also be considered as a co-responsible party in certain constellations.

For negatory claims, those persons who carry out the infringing act themselves (the user as the main perpetrator) and all those who do not carry out this act themselves but quasi consciously cooperate with the main perpetrator (so-called participants) can be covered by the law. However, not every connection to the main offense, no matter how small, is sufficient for participation; rather, the contribution must be somewhat close enough to the main offense to still be considered an adequate causal partial cause (see the decision of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court 145 III 72 considerations 2.3.1 et seq. (in German)). In our opinion, the provider can be considered a participant if he has already used the first work unlawfully for the training and the output of the AI application reflects this work.

Users of AI must therefore expect that a third party (rights holder) may prohibit them from continuing to use content generated by AI applications.

Providers of AI must therefore expect that the rights holder will prohibit them from reusing a work used for the training of AI models, i.e. from deleting it from the training data set (but not from the model without further ado).

For reparatory claims (e.g. damages), fault is required - in addition to the other bases for liability, such as the existence of damage and a causal link between the unlawful act and the damage. In other words, the conduct must be imputable to the main perpetrator and/or the participant because they contributed to the copyright infringement either intentionally or at least negligently. This is the case if the infringement was intentional or consciously accepted as a possibility or if the expected diligence was not exercised to prevent such an infringement. The standard of diligence that applies here depends heavily on the individual case.

If the user of the AI application uses an output that falls within the scope of protection of a third party, the user will usually lack intent, as it was neither foreseeable nor preventable for the user that the output would infringe the rights of third parties. Negligence will also be difficult to establish, as the user often lacks the opportunity to prevent the infringement by taking suitable precautions.

The risk for users to pay damages therefore only exists if (i) the infringement is deliberately provoked based on the content of the prompt, (ii) the infringement is obvious, or (iii) the rights holder has warned the user and the user has not stopped using it. If the infringement was intentional, criminal consequences are also possible.

In particular, the provider can be accused of contributory negligence if there is an original work, in the scope of protection of which the output of the AI application falls, was impermissibly part of the training data and the AI application simply reproduces this work.

International Copyright – Copyright Shopping?

As explained above, there are various uncertainties regarding the permissibility of using protected content for the training of AI models. In this respect, it may be interesting for providers of AI applications to design the training of the underlying model in such a way that it is not subject to Swiss copyright law.

Swiss law declares its own substantive law to be applicable if the protection of the intellectual property is claimed for Swiss territory (so-called "country of protection principle"; Art. 110 Para. 1 PILA), i.e. the copyright infringement takes place in Switzerland. However, if the AI model is trained in the USA by a USA company such as OpenAI, for example, the potential infringement must generally be assessed in accordance with USA copyright law. Each country independently defines the existence and scope of its intellectual property rights.

In principle, the country of protection principle enables AI providers to use copyright shopping to relocate training to those countries that allow them the widest possible use and/or legal certainty for the training. However, international agreements, in particular the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works ("BC"; SR 0.231.14), define certain minimum standards. With regard to the exception provisions relevant to AI training, Art. 9 para. 2 BC, for example, states that the reproduction of works without the consent of the rights holder may be made possible in certain special cases if neither the "normal exploitation of the work" nor the "legitimate interests of the creator" are unreasonably infringed. The extent to which AI training effectively impairs the normal exploitation of works remains to be seen. This is likely to be the case once the trade in content for AI training has become more established.

The answer to the question of what companies can now do specifically to reduce their risk of copyright infringement and how great this risk is will be dealt with in a separate article in our AI blog series.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.