In early 2000s and '10s, the Silk

Market in Beijing was among the "must-visit" places.

Although there undoubtedly were vendors selling bed sheets and

bathrobes made of the prized material, it was also a hotspot for counterfeit

goods. All one had to do was ask and a spritely vendor would

pull out a Dior or Prada bag, offering a starting price fractions

of what the original item would cost. Haggling is a must and would

reduce the price even further. While many such markets continue to

exist, regulators have put in restrictions and continue to shut

down such illegal practices. As with every other aspect of modern

life, the proliferation of the internet has changed the way

counterfeit goods are sold. Twenty or even ten years ago,

counterfeiting was an underground operation, much like the Silk

Market sellers concealing fake purses in storage bins. As social

media rose to prominence, however, you don't need to go far to

browse for counterfeit goods – create an Instagram account

and watch as your follower count rises thanks to bots advertising

shops with fake sunglasses, bags, jewelry and everything

else.

Social media is fueling the trade in counterfeit goods and shows no sign of stopping. Research shows that global trade in luxury goods, pharmaceuticals, and other counterfeits was a sizable $461 billion in 2013, and is projected to double by 2022. Losses incurred by luxury brands due to online counterfeiting amount to around $30 billion. OECD research shows that China and Hong Kong continue to top the list of exporters of fake goods.

Statements from companies such as Instagram and their parent giant Facebook continue to focus on the speed with which they respond to reports of counterfeit goods being sold on their platforms as well as algorithms they build to prevent such posts and accounts from ever reaching their audience, but each additional feature seems to create more opportunities for these sellers and more problems for the platforms. Many counterfeit sellers take to Instagram's stories, which disappear after 24 hours after posting, making it difficult to track down offenders. A recent update includes the ability to shop from within the platform itself.

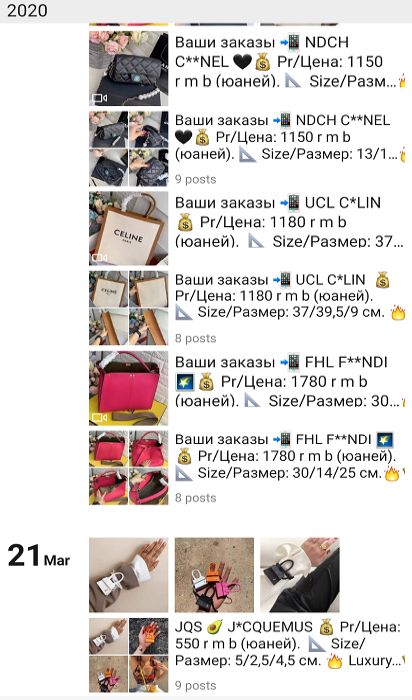

China and its online users are no strangers to counterfeit goods on social media, despite platforms like Instagram and Facebook being unavailable within its borders. While Chinese e-commerce websites like Taobao and Pinduoduo are familiar foes of brand owners, new channels for socializing like TikTok (Douyin in China) and established messaging platforms like WeChat are becoming new frontiers for sellers of counterfeit goods to reach bigger audiences. Accounts selling directly from factories where such goods are produced can be added to your contacts and post their latest offerings on their feed, sometimes censoring popular brand names, turning a listing for Louis Vuitton into L*uis V*itton in an effort to conceal their account from any potential algorithms searching for illegal activities. Counterfeits are advertised as being "luxury quality" and shipped with logo-stamped packaging, but at a fraction of the price. Because payment is fulfilled person-to-person through WeChat's payment system, regulating these transactions is a difficult task facing enforcers.

Shops on WeChat and Little Red Book advertise with images, which with improvements in technology can be tracked down – but that is not the case on Douyin, a platform where short videos prevail. Users can easily search using hashtags or keywords and find troves of fake luxury goods being advertised through short videos, which are more challenging for regulators to find.

China's recent E-Commerce Law sought to curb counterfeits which have been rampant in recent years by requiring using a real name, providing business registration, and other measures. The law applies to all operators of online business and places the burden of regulating individual sellers on their platforms. If a seller on WeChat is operating a counterfeit business, Tencent is liable for the seller's activities and should police these activities. While the adoption of the law is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, if the past decade has proven anything is that the online space is much more fluid and moves much faster than governments are used to and can issue regulations.

To monitor marks against counterfeiters in the ever-moving online space is a difficult process that requires a lot of manpower. Once a suspicious seller is identified, there are several avenues of action – a brand owner can issue a cease & desist letter through their legal representative in a certain jurisdiction, or an on-site investigation may be conducted; web notarization, especially if the counterfeiter is selling through social media, may be an effective tool to secure evidence. Further action may extend into an administrative investigation or even criminal action.

What are brand owners to do if they suspect their brand is being infringed online? Proactively monitoring a brand name across social media platforms is a great first step. While scrolling through photos on Instagram is a pastime for some, it is not a time-effective strategy for identifying counterfeits (the platform has 1 billion users per month). Technology does not only help proliferate counterfeits, however – it helps catch them too. Kangxin IP Platform offers monitoring reports for online brand protection, including searching across social media platforms counting the most users globally – Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, and Pinterest. The search report can be launched for an entire year, automatically sending monthly reports which include information about the seller, the goods, the number of followers of the suspicious account. This information can be then used to file complaints against the sellers and secure your IP in the elusive space of social media.

Originally Published 16 April, 2020

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.