On October 7th we provided you with a snapshot of the campaigns of each of Canada's Federal political parties and each of their respective carbon policies. With the election of a Liberal majority, everyone seems to be asking the question, where do we go from here on the climate change front?

Recall that, during the campaign, the Liberals proposed a "medicare" style approach to combating carbon emissions, which allows the provinces to design their own emissions platform within the confines of a national target and Federal oversight. The Liberals coined this plan as not too hot, not too cold, but just-right, striking an appropriate balance between the economic diversity inherent across the provinces and Canada's need to take a tougher stance on emissions. With Prime Minister Trudeau currently enjoying wide support during his post-election honeymoon period and the Paris climate change conference on the horizon, it appears that the Liberal government is employing an "all hands on deck" strategy in an effort to develop some consensus as to strategy and broad principles prior to the meetings in Paris. Certainly, there is an appearance of cohesion, at least outwardly, among the provinces and the Federal government as we approach the Paris conference. For businesses in Canada, it is important to anticipate where the Federal emissions target will be set and to begin to consider the effect such a target may have on the individual Canadian provinces.

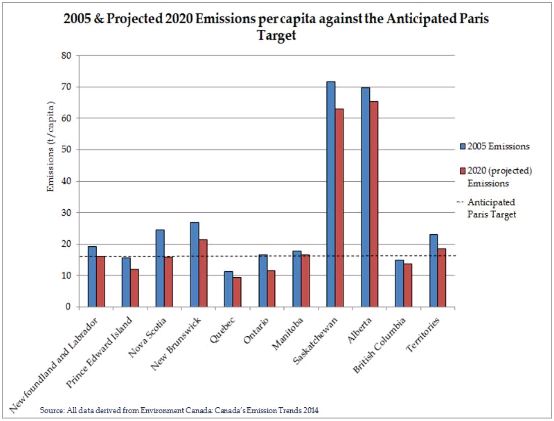

While the Liberals have yet to release specific emissions target details, it is reasonable to assume, and indeed has been suggested by several members of the Liberal cabinet, that their target will at least match the Conservative target of 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. However, in contrast to the previous Conservative target, which had no Federal enforcement and allowed Alberta and Saskatchewan to effectively "opt-out" of a national carbon initiative, the success of meeting a Federal target set by the Liberal's hinges on the combined efforts on behalf of each and every province. A closer look at the stark contrast in carbon emissions and political motivations across Canada demonstrates the difficult task ahead for Prime Minister Trudeau and his Liberal majority.

Based on the Environment Canada forecasts in Canada's Emissions Trends 2014, Alberta is expected to account for nearly 40% of Canadian emissions by 2020. All net emissions growth from 2005 is projected to occur in Western Canada, while the bulk of reductions are projected to occur elsewhere.

|

Provincial and Territorial Emissions: 2005 to 2020 (projected) (Mt CO2 eq) |

||||

|

|

2005 |

Percentage of Total |

2020 |

Percentage of Total |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

10 |

1.4% |

8 |

1.1% |

|

Prince Edward Island |

2 |

0.3% |

2 |

0.3% |

|

Nova Scotia |

23 |

3.1% |

15 |

2.0% |

|

New Brunswick |

20 |

2.7% |

16 |

2.1% |

|

Quebec |

86 |

11.7% |

80 |

10.7% |

|

Ontario |

207 |

28.1% |

170 |

22.8% |

|

Manitoba |

21 |

2.9% |

23 |

3.1% |

|

Saskatchewan |

71 |

9.6% |

73 |

9.8% |

|

Alberta |

232 |

31.5% |

287 |

38.5% |

|

British Columbia |

62 |

8.4% |

69 |

9.2% |

|

Territories |

2 |

0.3% |

2 |

0.3% |

|

Canada |

736 |

|

746 |

|

In particular, the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan are projected to have the highest per capita emissions output of any Canadian province or territory, even after the application of the reductions required under Alberta's recently announced Climate Leadership Report.

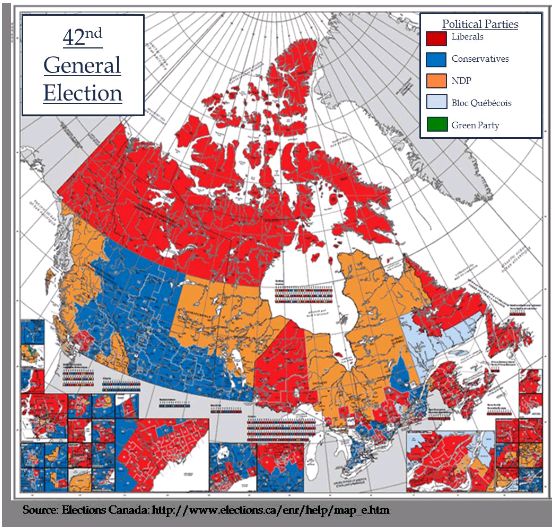

The contrast between Alberta, Saskatchewan and the rest of Canada is also evident in the election results illustrated by the electoral map below. While a national carbon policy did not appear to be a pre-election focal point, in hindsight, it appears to have been a strong indicator of the election results. Emissions in the Liberal heartland have been contained and are even decreasing, while emissions in Conservative strongholds of Alberta and Saskatchewan are projected to remain stable at best.

In essence, Canada's majority Federal government has been elected by the low per-capita carbon emitting provinces. As meeting any fixed Canadian emissions reduction target is an inter-provincial zero-sum game, lesser reductions in one province necessarily means the need for more reductions in others. The Federal government therefore finds itself having to strike a reasonable balance in the best interests of all Canadians that recognizes the relative strengths and weaknesses of the provinces, and the disparate impacts of climate change policy on certain regions and industries.

Recently, Alberta's Climate Change Advisory Panel released its Climate Leadership Report outlining its recommendations on future emissions regulation in Alberta. We have already produced an in-depth blog piece discussing the Report and the Alberta government's plan. Notably, the initial domestic response to Alberta's plan from industry, environmental organizations, various provincial governments, and the Prime Minister has been positive. There is wide recognition that Alberta is poised to tackle climate change in a meaningful way, while balancing economic realities. As noted in the Report, Alberta is much more exposed to carbon leakage than other provinces as much of its economy centres on emission-intensive industries with substantial exposure to emissions costs and competitive global market conditions. As climate change is a global issue, actual emissions reductions are not accomplished by imposing unduly aggressive actions without similar commitments from peer jurisdictions as investments in energy projects will simply shift to jurisdictions with less stringent carbon policies. The Federal government will have to grapple with this issue as driving prosperity out of Canada with no net reduction in global emissions would be unfortunate.

The Liberal climate agenda is still in its early days and there are many uncertainties going forward. However, the prominent appointment of Stéphane Dion to head the cabinet committee on climate and the renaming of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change demonstrates the Liberal's commitment to climate change policy. The public messaging around climate change is intending to highlight a committed leadership on this file. The Canadian provinces and the federal government will have a broad based delegation in Paris in the coming days with the appearance of some unity. Thereafter, they will meet again within 90 days to discuss a pan-Canadian framework for addressing climate change. Only time will tell whether a unified voice will remain as the details around the provinces' respective contributions to meeting of the national target is developed. It remains to be seen whether the Federal government can successfully bridge the differences on the climate change that exist across the differently situated provinces and work with the provinces to begin the inner workings of a national carbon program.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance of Luke Sinclair, articling student at law.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.