Gordon Moore is famous for having suggested, in 1965, that the evolution of electronics would be such that for the next 10 years, the number of components on a circuit would double every year.1 Nearly 50 years later, data demonstrates that the doubling rate was steady at 18 months. A variant to "Moore's law," the lesser known and lesser defined "Kryder's law," applies to hard disk capacity. Since 1956, the storage capacity on a single square inch went from 2,000 bits to a staggering 100 billion bits, a 50-million-fold increase.2

Needless to say, technology offers little pressure to limit the amount of information retained by organizations. The ease of keeping information, rather than closely managing it, leads to ever-growing, hard-to-manage information silos where finding relevant documents becomes a costly and often fruitless operation. As the cost of memory is driven down, the indirect costs of uncontrolled information retention are beginning to gather more attention. When it comes to using electronic documentation, proper Information Management (IM) is what makes the difference between real structural efficiencies and mere cost shifting and risk taking.

A proactive strategy

An organization is in a better position to meet its legal obligations and business needs surrounding the retention of records as well as the discovery phase of lawsuits and investigations if it has a strong control over its information (easy identification of custodians, types and formats of documents, location of systems and documents, etc.).

In a 2010 decision,3 Canadian plaintiffs before a US court were severely criticized for failure to administer proper discovery processes (notably, the failure to issue legal holds) within their organization, hence infringing on the rights of the defendants. Consequently, the plaintiffs had to support the reasonable costs of the defendant's motion (including attorney's fees) and some had to conduct supplemental discovery—at their own expense. Furthermore, the jury was instructed that it could make an adverse inference against the plaintiffs: it could infer that the missing documents would have been helpful to the defendants. As trans-border trade is ever more prevalent between Canada and the United States, being able to meet the strict American eDiscovery rules, which are influencing Canadian rules, is a first step towards reducing the risks and costs associated with lawsuits and investigations.

Aside from facilitating compliance with the legal obligations related to eDiscovery, proactive IM can also significantly reduce the risk caused by the unnecessary retention of records. Indeed, where retention of records finds its justification in laws, regulations or business needs, records that have no justification in being kept by an organization can be confidently disposed of. Systematic destruction of such records, based on a retention schedule, helps to keep the total volume of information to a minimum and also decreases the risk that an opposing party finds a "silver bullet" in the records while performing a document review. These are records that an organization could have legally destroyed long ago, but are currently prohibited from doing now that they are under a duty to preserve.

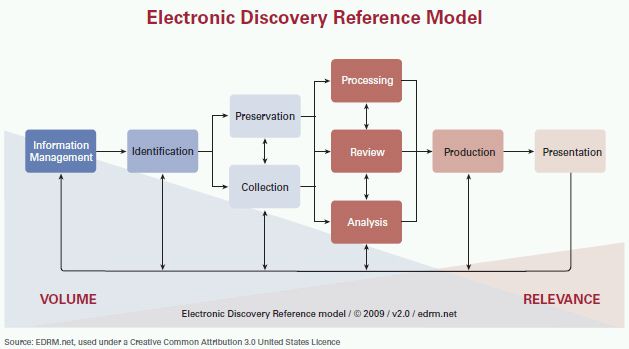

When IM reduces the volume of information, it also drives down the delays, the burden and, most importantly, the costs associated with the later stages of the eDiscovery process; the costs of preservation, collection, processing, reviewing and analysis are generally based on a per gigabyte of data structure. The Electronic Discovery Reference Model (shown on the following page) illustrates the relationship between the volume and relevance of information at the various stages of the process.

The general eDiscovery readiness of an organization relies in great part on the quality of its IM. A well thought-out and defensible plan to respond to discovery requests and legal hold notices and identify relevant documents should rely on good IM practices.

A holistic approach to IM projects

The standard approach to IM projects requires that a company's governance, technology and culture each be considered and addressed. While each of these factors constitutes distinct phases in a project, they should be closely integrated.

Preliminary assessment

Normally, the starting point of an IM project is a preliminary assessment. During a preliminary assessment, vital information for the project (such as the current state of governance, technology and culture, as well as the overall IM objectives) is gathered through document review and interviews, which will help define the scope of the project and form a practical project roadmap. The result of this preliminary review will be an IM Assessment (IMA). The IMA will provide an overview of the organization's informational landscape and evaluate its maturity in terms of IM.

On the governance front, the policies and other documented processes of the organization should be reviewed to complete a gap analysis in comparison to best practices and other market benchmarks. A common finding is that some essential elements of the IM framework are scattered across various policy documents and operational groups. This alone highlights the need for a global, standardized and coherent approach to IM throughout the organization. This initial assessment and the ensuing recommendations should provide a roadmap for the project.

The second component of an IMA seeks to take a snapshot of the organization: its business units and departments, its various locations and jurisdictions, its corporate structure and, of course, an in-depth view of the information technologies in place. The quality of the IM framework to be put into place—the policies, procedures and technological solution—depends on the quality of the information gathered at this stage.

Policies, procedures and protocols development

Following the IMA, and in order to fully benefit from its findings, the second part of an IM project will generally be the drafting or modification of governance documents, such as policies, procedures and protocols. Policies are by nature higher level documents that reflect best practices, corporate objectives and the unique aspects of the organization. The overarching IM policy sets out the IM framework for the organization, which often involves the creation of an IM Committee to ensure that the organization and its workforce comply with and abide by the principles set out in the underlying policies.

The policies themselves should be drafted in a technologically neutral fashion so as to reflect the IM objectives and needs of an organization, rather than the technological means through which they will be met. This also allows for the management of both electronic and paper documents.

Procedures and protocols are more precise documents that support the policies and will help to operationalize them. For instance, when it comes to document disposal, handling confidential and personal information requires specific precautions, which, in turn, relies on the proper classification of the documents when they are created. The use of a common set of metadata4 and well-designed workflows allows for this to be managed and accomplished seamlessly. By using technological tools, an organization is able to automate its procedures and workflows to the maximum extent. That is where the real return on investment resides.

Technology selection and implementation

The choice of a technology solution is a multi-faceted process. It will build on and take into account the technical information gathered in the IMA, the specifics of the organization's resources (human, material and financial) and, of course, the various products available in the market. In order to make an informed decision, there is a clear benefit to accessing independent third parties who understand the market and can objectively assist the organization in selecting the solution that meets its needs. This may involve drafting a call for tenders; designing an evaluation grid; and participating in the interviews with the providers, vendors or integrators.

Once the solution has been chosen, the implementation should be proactively managed, which will require project managers with change management expertise. This process needs to ensure that costs, schedules and specific requirements are met so that employees can painlessly adopt and use the solution moving forward.

Culture

Cultural considerations of IM projects are perhaps the most critical. As the objectives of an IM project generally imply company wide or, at a minimum, departmental changes to working habits, one of the biggest challenges is to obtain employee acceptance and commitment. Indeed, many employees may question why changes are required when current practices, in their view, work well. This is the core of IM projects' cultural considerations. Communication, information, reminders and personal involvement are elements of change management that must be looked at and understood from the first day of the project.

Another function of the IM committee set up in the overarching IM policy is to ensure proper awareness and training of employees. The objective should be to ensure that each employee knows his or her personal role and responsibilities related to information and documents.

Conclusion

Information ought to be considered an asset as important as human, material and financial resources; it should be managed accordingly.

Keeping too much information not only involves costs and leads to inefficiencies, it is also a source of risk. Information that is no longer required for business or regulatory/legal compliance is a potential liability. Risks will likely materialize during investigations or as a result of the legal discovery process. For example, there is often an inability to quickly identify relevant custodians or find documents, or there are difficulties in demonstrating the authenticity of documents. Keeping too much information also leads to higher discovery costs due to the quantity of information to be processed. These problems are the result of IM issues.

IM provides a workable approach and real solutions to such issues. A holistic approach to IM projects will deal with the inherent and multi-faceted complexities of managing a significant and growing volume of information. It also adapts to similar projects, such as enhancing eDiscovery preparedness or migrating from paper to electronic documentation. In the end, just because technology enables us to store unimaginable quantities of information, it doesn't mean that all information that is produced should be kept.

Footnotes

1. Gordon E. Moore, "Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits," Electronics Magazine, April 19, 1965, p. 114–117.

2. Chip Walter, "Kryder's Law", Scientific American, July 25, 2005, online: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=kryders-law.

3. The Pension Committee of the University of Montreal Pension Plan, et al. v. Banc of America Securities LLC, et al., No. 05 Civ. 9016 (SAS), 2010 WL 184312 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 15, 2010).

4. Metadata is, literally, information about information: date of creation, author, document type, confidentiality level, keywords, etc. It allows for better retrieval, identification and overall management of documents.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.