Overview

Canadian private M&A and business practice are very similar to the US. As such, US buyers can generally expect fewer surprises heading north than into other foreign jurisdictions. For these and other reasons, Canada is one of the most popular destinations for US outbound M&A, both in deal volume and deal value.

We've prepared this overview of private M&A into Canada to facilitate cross-border investment. Given the high-level similarities in law and market practice between our countries, we've focused on major differences and the most relevant considerations for US buyers coming into Canada.

US / Canada Cross-Border M&A Statistics

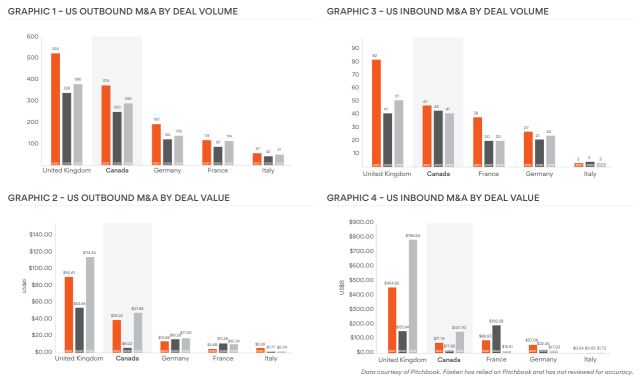

Canada is consistently amongst the most popular destinations for outbound US investment. Indeed, Canada routinely ranks second behind only the U.K. in outbound US M&A by deal volume and within the top five destinations for US outbound M&A by deal value. Similarly, Canada is routinely amongst the top three largest sources of US inbound M&A by both deal volume and deal value.

To illustrate, the following graphics represent outbound and inbound US M&A for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021 involving four other of the US' most common trade partners historically, namely the U.K., Germany, France, and Italy. Notably, even though each of these countries has a GDP larger than Canada's, only the U.K. ranks higher than Canada as a destination for US outbound M&A.

Deal Structure & Tax Considerations

Below follow some of the key transaction structuring considerations for a US buyer acquiring a Canadian target.

| Canadian AcquireCo | The typical structure of US inbound M&A into Canada involves the incorporation of a Canadian special purpose corporation (AcquireCo) by the US buyer. Use of an AcquireCo maximizes paid-up capital, which facilitates future cross-border distributions without Canadian withholding tax (by contrast, dividends would result in Canadian withholding tax). Following closing, AcquireCo will "amalgamate" with the target. In circumstances where the inbound transaction involves acquisition financing by AcquireCo, an amalgamation may allow for the deduction of the interest component of debt payments by the amalgamated entity. Specifically, as Canada does not have consolidated tax reporting, the amalgamation is necessary to effectively push down the debt to the target. |

| Exchangeable Share Structures | Where a US buyer seeks to pay a Canadian resident seller wholly or partly in shares rather than entirely in cash, certain Canadian tax issues may arise. In particular, the sale of shares of a Canadian corporation by a Canadian resident seller in exchange for equity of a non-Canadian entity does not qualify for a tax deferral and may result in Canadian taxes arising from any gain realized by the seller on the sale. A Canadian resident seller's tax liability could prevent the seller from proceeding with a sale to a US buyer where it receives insufficient cash consideration from the buyer to fund this tax liability. Canadian tax law only provides for a tax deferral where a Canadian resident seller receives shares of a Canadian corporation. To facilitate a tax deferral for a Canadian resident seller, a US buyer can arrange for its Canadian subsidiary to pay the seller with shares in its capital stock that are exchangeable, at the option of the seller, into the US buyer's shares. These exchangeable shares are the economic equivalent of the US buyer's shares (i.e., which mirror all rights attaching to the US buyer's shares, including regarding dividends and liquidation entitlements). Because the Canadian resident seller receives shares issued by a Canadian corporation as consideration for the sale of the target shares, the Canadian seller may elect to defer the Canadian tax on all or a portion of the gain arising from the sale until the exchangeable shares are exchanged for those of the US buyer. |

| Corporate Entities | Unlimited liability corporations (ULCs) are sometimes used in cross-border deals. ULCs differ from limited corporations in that ULC shareholders can be held personally liable for the debts of the company in the event of insolvency. ULCs are treated the same as limited corporations under Canadian federal income tax. However, from a US federal income tax perspective, ULCs can be treated as flow-through entities. ULCs are available under the laws of the provinces of Alberta, British Columbia and Nova Scotia. |

| Amalgamations | The closest Canadian equivalent to the US concept of merger is an amalgamation. Unlike a merger, where one company "survives" and the other ceases to exist, the amalgamating companies all continue as a single corporate entity with the amalgamated corporation possessing all of the assets, rights and liabilities of each of the amalgamating corporations. To achieve a US-style absorptive merger under Canadian law requires a court-approved plan of arrangement whereby the court decrees that only a single predecessor survives the amalgamation. Amalgamations are often used in US inbound private M&A as discussed above (see "Canadian AcquireCo"). Plans of arrangement are much more common in Canadian public M&A than private M&A. |

Deal Terms: Differences in Law on Key Points

Canadian contract law is similar to New York and Delaware law in many respects. That said, there are several differences that may impact M&A negotiations and agreements.

Ordinary Course Covenants

Canadian caselaw on ordinary course covenants is complex and has sent more mixed messages than its Delaware counterpart. Issues to be navigated with caution include the impact of a "consistent with past practice" qualifier, whether the ordinary course will include extraordinary measures in response to extraordinary events, and the impact of a proviso allowing deviation from the ordinary course with the buyer's consent. Unlike in Delaware, Canadian courts have held that ordinary course covenants and MAE clauses should read closely together.

MAE Clauses

Canadian courts have looked to Delaware in interpreting and applying MAE clauses. However, notable differences persist. While Delaware courts have been clear that an MAE analysis is an objective analysis and not a subjective analysis, Canadian courts have been inconsistent on the point. In adition, while Delaware no longer requires an MAE to arise from an "unknown" risk, Canadian courts have not dispensed with this requirement. Finally, while Delaware courts regularly caution that MAE clauses impose a "heavy burden" on the buyer, Canadian courts have given the ambiguous (and somewhat opposite) instruction that MAE clauses are to be "interpreted from the buyer's perspective".

Sandbagging

States such as Delaware are understood to be receptive to sandbagging such that they will enforce a pro-sandbagging clause and allow a buyer to claim on a breached seller representation and warranty even where the buyer had knowledge of the inaccuracy prior to execution. Caselaw on sandbagging in Canada is very thin with the few courts that have considered the issue having sent conflicting signals. Moreover, these decisions predate significant developments in Canadian law imposing duties of good faith and honest performance in contractual relations. Buyers can negotiate for a pro-sandbagging clause but it may be of limited value. Sellers can negotiate for an anti-sandbagging clause but it may be redundant. Common market practice in Canada is to remain silent on the issue.

Specific Performance

Specific performance is generally characterized as an exceptional remedy under Canadian law with Canadian courts often reluctant to award it, even in the face of an express specific performance clause. Regardless of what M&A counterparties have contractually agreed, specific performance remains an equitable remedy at the discretion of the court. While the same is generally the case in the US, courts in certain states such as Delaware often exhibit a greater respect for the freedom of contract and deference to contractually agreed remedies than do their Canadian counterparts.

Antitrust (Competition)

Antitrust

As of 2023, subject to certain exceptions, acquisitions of Canadian companies that exceed the "party-size" threshold and "transaction-size" threshold are subject to pre-merger notification. Asset values are calculated having regard to the book value of the assets in Canada rather than the fair market value of the assets in Canada.

For the party-size threshold, the parties to the transaction, together with their affiliates, must have assets in Canada or annual gross revenues from sales in, from or into Canada exceeding C$400 million. For the transaction-size threshold, the value of assets in Canada of the target, or the gross revenues from sales in or from Canada generated by those assets, must exceed C$93 million. The foregoing dollar amounts are subject to annual adjustment.

If each of the applicable thresholds is exceeded, the merging parties are required to provide prescribed information to the Competition Bureau (the "Bureau") and they cannot complete the transaction until the statutory waiting period under the Competition Act has expired or has been terminated or waived by the Commissioner of Competition (the "Commissioner"). The statutory waiting period expires 30 days after all prescribed information has been provided to the Bureau unless, prior to the end of this initial 30-day period, the Commissioner issues a Supplementary Information Request (which is the equivalent of a Second Request in the US).

If a Supplementary Information Request is issued, the statutory waiting period expires 30 days after the merging parties have complied with the Supplementary Information Request. In our experience, it generally takes a few weeks to several months for the merging parties to respond to a Supplementary Information Request, depending on the nature and scope of the information requested by the Bureau.

Substantive Merger Review

All mergers, regardless of whether they are subject to pre-merger notification, may be subject to substantive review under the Competition Act. In this regard, the term "merger" is defined broadly to mean "the acquisition or establishment, direct or indirect, by one or more persons, whether by purchase or lease of shares or assets, by amalgamation or by combination or otherwise, of control over or significant interest in the whole or a part of a business of a competitor, supplier, customer or other person".

The Commissioner reviews mergers in order to determine whether they result in, or are likely to result in, a substantial prevention or lessening of competition. As part of this analysis, the Commissioner considers a number of factors, and the Commissioner's approach is detailed in the Bureau's Merger Enforcement Guidelines. The length of the Commissioner's review varies depending on whether a merger is designated as "non-complex" or "complex". While the review of "non-complex" mergers typically takes no more than 14 days, the review of complex mergers can, in certain cases, exceed 150 days (such as when a Supplementary Information Request has been issued).

If the Commissioner concludes that a merger results in, or is likely to result in, a substantial prevention or lessening of competition, she or he will normally attempt to resolve her or his concerns with the parties. If a resolution cannot be reached with the parties, the Commissioner can apply to the Competition Tribunal (the "Tribunal") for an order.

Click here to continue reading . . .

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.