1 Legislative framework

1.1 Which legislative provisions govern private client matters in your jurisdiction?

In Australia, each state and territory has legislative provisions that govern private client matters.

Each jurisdiction within Australian generally has the following laws:

- Trustee Acts, which govern trusts and the rights and duties of trustees;

- Wills Acts or Succession Acts, which govern the creation and interpretation of wills;

- Administration Acts or Administration and Probate Acts, which govern probate matters and the administration of deceased estates, and which allow certain people to make a claim for provision from a deceased person's estate;

- Guardianship and Administration Acts, which oversee the financial and personal decisions of persons who have lost capacity;

- Power of Attorney Acts, which govern the making and operation of powers of attorney;

- Family Law Acts, which govern matrimonial matters; and

- various Duties Acts and Tax Acts, which govern duties payable on the transfer of dutiable assets and various taxes associated with the transfer of assets, whether through a deceased estate or otherwise.

The laws in each state and territory vary slightly, and usually the domicile of the deceased or the location of any real property will determine which laws are applicable.

1.2 Do any special regimes apply to specific individuals (eg, foreign nationals; temporary residents)?

There are no special regimes that apply to specific individuals in Australia. Generally, a person's residency status determines his or her exposure to income tax and other taxes in Australia on income derived in Australia and elsewhere.

However, surcharges may apply depending on the status of a person's residency, such as foreign purchaser surcharge duty on the acquisition of residential property.

1.3 Which bilateral, multilateral and supranational instruments in effect in your jurisdiction are of relevance in the private client sphere?

There are numerous bilateral, multilateral and supranational instruments in effect in Australia which are relevant in the private client sphere. Australia has over 50 double tax agreements with other countries which provide for either income tax exemptions or reduced rates.

Australia has also entered into bilateral agreements with a number of countries in relation to the exchange of information in relation to taxes.

Australia has enacted the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (MLI), which it signed on 7 June 2017. The MLI has been ratified, which means that it applies to 'covered countries' such as Belgium, Canada, France, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Singapore and the United Kingdom.

Other important agreements to which Australia adheres and which affect private clients include:

- the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Cth); and

- the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth).

2 Taxation

2.1 On what basis are individuals subject to tax in your jurisdiction (eg, residence/domicile/nationality)? How is this determined?

There are four tests to determine whether a person is an Australian tax resident. These are outlined as follows.

Residency status: The commissioner of taxation will consider the following:

- physical presence;

- intention and purpose;

- the location of your family;

- business or employment ties;

- maintenance and location of assets; and

- social and living arrangements.

If an individual does not satisfy the residency test, he or she may still be considered an Australian tax resident if any of the statutory tests below are satisfied:

- Domicile test: The domicile test assesses an individual's permanent residence. If the commissioner is satisfied that an individual's permanent home is located in Australia, he or she will be liable to pay tax in Australia.

- 183-day test: If an individual spends at least 183 days per calendar year in Australia, whether continuously or not, the individual will be considered an Australian tax resident.

- Superannuation test: An individual will be considered an Australian tax resident if he or she, or his or her spouse, is a contributing member of a public sector superannuation scheme of the Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme.

If the commissioner is satisfied that an individual is an Australian tax resident, he or she may be required to pay:

- income tax;

- land tax on any real property owned by the individual, subject to exemptions for a principal place of residence;

- goods and services tax; and

- capital gains tax.

2.2 When does the personal tax year start and end in your jurisdiction?

In Australia, the personal tax year is referred to as a financial year. The financial year runs from 1 July to 30 June of each year.

2.3 With regard to income: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Australian tax residents must pay income tax on their personal taxable income, including from employment, business interests, dividends, trust distributions, foreign income and the like.

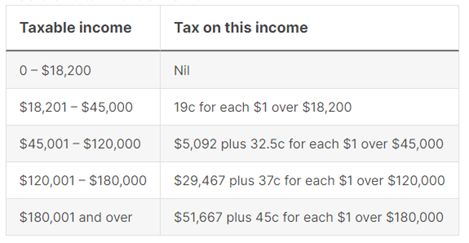

The marginal income tax rate increases according to the level of income earned. For the 2023–2024 financial year, the marginal income tax rates are as follows.

For the 2024–2025 financial year, the proposed changes to marginal income tax rates are as follows:

- Reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%;

- Reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%;

- Increase the threshold above which the 37% tax rate applies from A$120,000 to A$135,000; and

- Increase the threshold above which the 45% tax rate applies from A$180,000 to A$190,000.

The above rates do not include the Medicare levy of 2%, which is payable to fund Medicare, the national healthcare provider in Australia.

High-income earners may also be liable to pay the Medicare levy surcharge (MLS), an additional levy payable by individuals who reach a certain level of income and do not have private health insurance. In this instance, the government imposes a further levy which is calculated at approximately 1% to 1.5% of the individual's taxable income over and above the existing Medicare levy of 2%.

The MLS encourages those who can afford private health insurance to obtain appropriate health coverage for themselves and their dependants, thus reducing the financial burden on Medicare.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The calculation of taxable income depends on its nature.

An employee is generally taxed on all remuneration and benefits received in the relevant tax year. A company's contributions to an employee's superannuation scheme are generally not taxable.

Further, net profits from rental property after the deduction of qualifying expenses which were incurred wholly and exclusively for the property rental business are also added to an individual's income for that financial year. The types of expenses that can be deducted include:

- mortgage interest;

- the costs of general maintenance and repairs to the property (provided that they are not improvements);

- utility costs;

- insurance;

- letting agent fees and management fees; and

- accountant's fees.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

An Australian tax resident must file an income tax return on a self-assessment basis where his or her gross income exceeds the tax-free threshold of A$18,200. A non-resident earning more than A$1 of Australian-sourced income must file a return. There is no joint assessment or joint filing in Australia.

The tax return is due for filing by the following 31 October, unless an extension is available.

Once a tax return is lodged, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) will issue an income tax assessment of the taxable income/tax loss and tax payable (if any) to the individual based on the income tax return. If there is a tax liability, it is usually payable by May before the commencement of the next financial year.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

In Australia, the first A$18,200 of income earned is considered tax free. Every A$1 earned over the A$18,200 is taxable. There are certain deductions and reliefs available, such as the following:

- Income from rental properties is taxed only after the deduction of costs and expenses for operating the rental property;

- There is a deduction for out-of-pocket work-related expenses; and

- There are deductions for:

-

- the cost of managing tax affairs;

- charitable donations to registered charitable organisations; and

- interest, dividend and other investment income.

2.4 With regard to capital gains: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

An individual is liable to pay capital gains tax (CGT) on the profits generated upon disposal of an asset. Any CGT payable will form part of an individual's income tax and will be assessed at the marginal income tax rates.

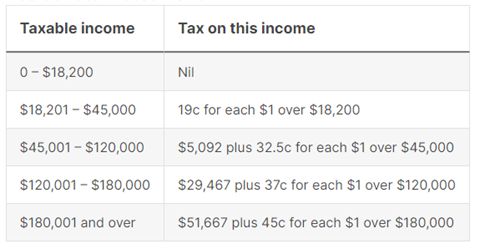

For the 2023–2024 financial year, the marginal income tax rates are as follows:

For the 2024–2025 financial year, the proposed changes to marginal income tax rates are as follows:

- Reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%;

- Reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%;

- Increase the threshold above which the 37% tax rate applies from A$120,000 to A$135,000; and

- Increase the threshold above which the 45% tax rate applies from A$180,000 to A$190,000.

Any income generated by a company is taxed at a marginal rate of 30%; and for trusts, any income accumulated (not distributed to beneficiaries) is taxed at a marginal rate of 45%.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

CGT is calculated by first determining the cost base of the asset. The cost base is what it cost to acquire the asset, together with the costs incurred in acquiring, holding and disposing of the asset. Once the cost base has been determined, these costs are subtracted from the amount received on disposal of the asset. Capital losses can be subtracted from capital gains.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

An Australian tax resident must file an income tax return on a self-assessment basis where his or her gross income exceeds the tax-free threshold of A$18,200. A non-resident earning more than A$1 of Australian-sourced income must file a return. There is no joint assessment or joint filing in Australia.

Gross income includes any capital gains made on the disposal of an asset.

Once a tax return is lodged, the ATO will issue an income tax assessment of the taxable income/tax loss and tax payable (if any) to the individual based on the income tax return. If there is a tax liability, it is usually payable by May before the commencement of the next financial year.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

A 50% CGT discount is available on a capital gain if the individual owned the asset for at least 12 months and is an Australian tax resident.

Any costs in acquiring an asset are factored into the cost base calculations to determine the gain on a disposal of the asset.

Additional discounts of up to 10% are available for Australian individuals who provide affordable rental housing to people earning low to moderate incomes. On the disposal of such residential rental properties, the Australian homeowner could obtain a discount of up to 60%.

2.5 With regard to inheritances: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

There are no inheritance or estate taxes payable in Australia. There is no tax payable for transmission of assets from the estate to beneficiaries. However, if an estate asset is sold to a third party, CGT may be payable by the estate upon disposal of the asset.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

There is no taxable base for inheritances.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

The legal personal representative of an estate is responsible for lodging a tax return on behalf of the deceased for the year of his or her death, called a 'date of death return'. Subsequently, an estate tax return must be lodged for income earned by the estate for each financial year until the estate is fully administered.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

There are no exemptions, deductions or other forms of relief available.

2.6 With regard to investment income: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Tax on investment income is based on how the investments are owned. For example, assets may be owned by an individual, a company or a trust structure.

For investments owned in a personal capacity, the investment income is added to the individual's overall income, including employment income, and taxed at the marginal income tax rates.

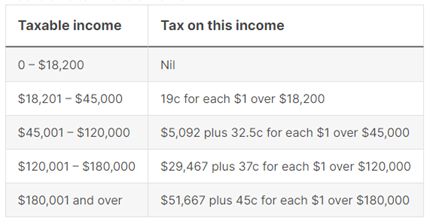

The marginal income tax rate increases according to the level of income earned. For the 2023–2024 financial year, the marginal income tax rates are as follows:

For the 2024–2025 financial year, the proposed changes to marginal income tax rates are as follows:

- Reduce the 19% tax rate to 16%;

- Reduce the 32.5% tax rate to 30%;

- Increase the threshold above which the 37% tax rate applies from A$120,000 to A$135,000; and

- Increase the threshold above which the 45% tax rate applies from A$180,000 to A$190,000.

Any income generated by a company is taxed at a marginal rate of 30%; and for trusts, any income accumulated (not distributed to beneficiaries) is taxed at a marginal rate of 45%.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The taxable base of investment income is calculated by classifying the investment income and deducting any related expenses incurred to earn that income.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

In the case of investment income for assets owned by an individual in his or her personal capacity, the individual must allocate such income to his or her individual tax return. An Australian tax resident must file an income tax return where his or her gross income exceeds the tax-free threshold of A$18,200. A non-resident earning more than A$1 of Australian-sourced income must file a tax return. There is no joint assessment or joint filing in Australia.

The tax return is due for filing by the following 31 October, unless an extension is available.

Once a tax return is lodged, the ATO will issue an income tax assessment of the taxable income/tax loss and tax payable (if any) to the individual based on the income tax return. If there is a tax liability, it is usually payable by May before the commencement of the next financial year.

A corporation – which includes the parent company of a tax consolidated group – can lodge a tax return under a self-assessment system that allows the ATO to rely on the information stated on the return. However, the ATO conducts audits to ensure that corporations are compliant with their tax requirements. If a corporation has doubts as to its tax liability regarding a specific item, it can request the ATO to consider the matter and issue a binding private ruling.

Generally, the tax return for a corporation must be filed with the ATO by 15 January or such later date as the ATO allows. Additional time may apply where the tax return is filed by a registered tax agent.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

As with a person's income, in Australia, the first A$18,200 of income earned is considered tax free. Every A$1 earned over this threshold is taxable. There are certain deductions and reliefs available, such as for:

- income from rental properties – only income earned after the deduction of costs and expenses for operating the rental property is taxed;

- other expenses, such as the costs of managing one's tax affairs; and

- dividend and other investment income.

Further deductions and relief are available for corporations, such as:

- depreciation and depletion for the decline in value held by the taxable entity;

- start-up expenses such as incorporation costs;

- interest expenses;

- bad or forgiven debts; and

- charitable contributions.

Losses can also be carried forward indefinitely, subject to certain compliance requirements.

2.7 With regard to real estate: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Land transfer duty (also known as stamp duty), land tax, council rates and CGT are the main taxes which apply to an individual's real property.

Stamp duty is tax payable upon the acquisition of real property. Stamp duty is calculated based on the dutiable value of the property and whether any concessions or exemptions are available. Different rates of stamp duty are generally payable by foreign residents. Concessions and/or exemptions are available in various circumstances, including:

- for eligible first-home buyers; and

- in other circumstances, such as transfers between spouses (or ex-spouses) or between trusts and beneficiaries.

An annual land tax is generally payable on the taxable value of real property. An individual's principal place of residence is generally exempt from land tax.

Council rates are payable to the municipal council to cover the costs of local government services such as waste management. Council rates are calculated based on an assessment of capital improved value undertaken by the municipal council.

CGT is payable by the vendor upon the sale or disposal of dutiable property other than a principal place of residence.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

Taxes and duties relating to real estate are determined on a sliding scale depending on the value of the property. CGT is determined on the gain attributed from the purchase price less any costs for the maintenance of the property. The capital gain is then allocated to the company, trust or individual's taxable income for that financial year.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

There are no specific tax return requirements; these taxes and duties should be accounted for in the individual, trust or company's tax lodgements for each financial year.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

Land transfer duty exemptions are available for first-home owners in Australia, subject to satisfying certain requirements, such as:

- the property being the individual's primary residence; and

- the value being under a threshold amount.

Land tax is not generally paid on primary residences.

Upon the sale of a primary residence, no CGT is payable; however, on disposal of any other real estate held for more than 12 months, a 50% discount of any taxable gain is available on the disposition. CGT may be rolled over (or deferred) in certain circumstances, including:

- a transfer between spouses upon the breakdown of a marriage or relationship; or

- the loss or destruction of the asset.

2.8 With regard to any other direct taxes levied in your jurisdiction: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

Companies are subject to a tax rate of 30% on taxable income, except for 'base rate entities', which are subject to a reduced tax rate of 25% for the 2020/2021 financial year and future years. Base rate entities are companies:

- which have an aggregate turnover of less than A$50 million; and

- where 80% or less of their assessable income is passive income such as royalties and rent, interest income or a net capital gain.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

The taxable base is calculated by classifying the income generated by the company and deducting any related expenses incurred to earn that income.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

A company must lodge an annual company tax return. Generally, the lodgement and payment date for small companies is 28 February. If any prior year returns are outstanding, the due date will be 31 October.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

A company can claim a tax deduction on expenses incurred in carrying on its business, provided that those expenses relate to the earning of the assessable income. A company can claim for deductions if:

- the expense was used for the business; or

- the expense was used for a mix of business and personal use, in which case only the business use may be claimed and there must be records to substantiate the deduction.

2.9 With regard to any indirect taxes levied in your jurisdiction: (a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates? (b) How is the taxable base determined? (c) What are the relevant tax return requirements? and (d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

(a) What taxes are levied and what are the applicable rates?

A large component of indirect tax in Australia is goods and services tax (GST). GST applies to any form of supply that is:

- made for consideration in the course or furtherance of an enterprise;

- connected with Australia; and

- provided by an entity that is either registered or required to be registered for GST.

The GST rate in Australia is 10%.

(b) How is the taxable base determined?

For all goods and services which are subject to GST, an additional 10% is applied.

(c) What are the relevant tax return requirements?

The annual payment date for GST is 31 October of each year as displayed on a business activity statement (BAS). The BAS reports GST, the company's pay as you go (PAYG) instalments, PAYG withholding tax and other taxes. Some entities must report monthly or quarterly, depending on turnover.

(d) What exemptions, deductions and other forms of relief are available?

There are no exemptions or deductions available. GST-free (zero-rated) supplies include:

- exports (of goods and services);

- some food products;

- most medical and health products and services;

- most educational courses;

- childcare;

- religious services;

- water;

- sewerage and drainage services; and

- international transport.

Input taxed (exempt) supplies include:

- financial supplies;

- residential rent and sales of residential premises;

- upon election, long-term accommodation in commercial residential premises; and

- fundraising events conducted by charitable and not-for-profit entities.

3 Succession

3.1 What laws govern succession in your jurisdiction? Can succession be governed by the laws of another jurisdiction?

Each jurisdiction within Australian generally has the following laws:

- a Trustee Act, which governs trusts generally and the rights and duties of trustees;

- a Wills Act or Succession Act, which governs the creation and interpretation of wills; and

- an Administration Act or Administration and Probate Act, which:

-

- governs probate matters and the administration of deceased estates; and

- allows certain people to make a claim for provision or further provision from a deceased estate.

Generally, a valid will determines how assets will be disposed of when a person dies. However, if a person dies intestate (without a will):

- with respect to his or her movable property, the law of the domicile of the deceased will determine the beneficiaries and the share of each beneficiary to such property held in Australia, including if the deceased was domiciled outside of Australia; and

- with respect to immovable property, the lex situs – that is, the law where the real asset is situated – will determine the beneficiaries regardless of the domicile of the deceased. Thus, if a person dies domiciled outside of Australia leaving real estate within Australia, those assets will be distributed to the beneficiaries entitled to them under Australian law.

3.2 How is any conflict of laws resolved?

In Australia, there is no distinction between real and personal property for the purposes of conflicts of law. Rather, there is a distinction between movable and immovable property. Whether a thing is movable or immovable will be decided by the lex situs (ie, the law of the place where the property is situated).

'Movable property' includes chattels not attached to land and other assets that are movable, such as bank accounts and shares. 'Immovable property' is land and all interest in land such as title deeds and fixtures.

The general rule is that, irrespective of domicile, the law of the lex situs will determine the succession of the property within the lex situs in relation to immovables. However, with regard to movables, the law of the deceased's domicile at the date of death will apply.

3.3 Do rules of forced heirship apply in your jurisdiction?

Australia does not have forced heirship provisions.

3.4 Do the rules of succession rules apply if the deceased is intestate?

Each state and territory in Australia has provisions which determine the distribution of a deceased person's estate if he or she has died intestate. The jurisdiction in which the person resided or had assets will determine which laws apply. For example, some states provide that the spouse (if any) will receive the entire residue of the deceased person's estate; if there is no spouse, then children; if there are no children, then parents and so on.

Other jurisdictions split the residuary estate between spouses and children and can also include multiple de facto partners.

3.5 Can the rules of succession be challenged? If so, how?

Each state and territory in Australia has its own laws enabling eligible applicants to make a claim for provision or further provision against a deceased estate. Generally, for an application to succeed, the following elements must be satisfied.

Eligible applicant: The following persons are generally considered to be eligible applicants:

- a spouse or domestic partner of the deceased at time of death;

- a child, including a stepchild, of the deceased; and

- a person who was wholly or partially dependent on the deceased, to the extent the deceased had a moral obligation to provide for that person in the will.

Relevant considerations: A claim must generally be made within six months of grant of representation being issued by the court in some jurisdictions; while in others, a claim must be made within 12 months of the date of death of the deceased. When assessing the validity of a claim, the court will consider various factors, including:

- the terms of the deceased's will (if any);

- evidence of why the deceased drafted his or her will in a certain way; and

- any evidence as to the deceased's intentions in relation to provision for the applicant.

The court may also consider other factors, such as:

- the size of the estate;

- the relationship between the deceased and the applicant;

- the applicant's personal and financial circumstances;

- the circumstances of the other beneficiaries; and

- any other circumstances that the court sees fit.

Australian courts place a strong focus on whether the deceased had a moral obligation and the adequacy of any provision made. They also consider whether the applicant has a need for provision from the estate.

4 Wills and probate

4.1 What laws govern wills in your jurisdiction? Can a will be governed by the laws of another jurisdiction?

In Australia, each state and territory has its own legislation governing wills and the administration of estates.

Australia also recognises wills executed in foreign places. A will is deemed to be valid if its execution conforms to the requirements for a valid will in the jurisdiction in which it was executed.

4.2 How is any conflict of laws resolved?

The laws of the jurisdiction in which the will was executed will apply to determine whether the will was validly executed. The domicile and the nature of assets will determine the jurisdiction in which the will is proven. Generally, the jurisdiction of the deceased's domicile and the location of assets will determine where the will is proven and before which court an application for grant of representation should be made.

4.3 Are foreign wills recognised in your jurisdiction? If so, what process is followed in this regard?

Australia recognises international wills. An 'international will' is a document executed by the testator with the intention that it will apply in any jurisdiction in the world. Australia is a party to the Uniform Law on the Form of an International Will contained in the UNIDROIT Convention. The convention was signed in Washington DC in 1973. Australia has adopted the principles in the convention which stipulate that an international will is recognised as a valid form of will by the courts of countries that are party to the convention.

4.4 Beyond issues of succession discussed in question 3, are there any other limitations to testamentary freedom?

Testamentary freedom is balanced against the testator's moral responsibility to certain eligible persons such as spouses or children, to make proper provision for their adequate maintenance and support. If a testator has failed to make adequate provision for such persons, the will may be subject to challenge.

The courts also consider whether the eligible person has a need for provision or further provision from the estate.

4.5 What formal requirements must be observed when drafting a will?

Generally, for a will to be valid in Australia, it must be:

- in writing;

- signed by the testator with the intention of executing a will; and

- signed in the presence of two witnesses present at the same time.

The testator must also have full legal capacity to make a will and must not be unduly influenced.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the states and territories have enacted legislation to allow wills to be signed electronically, whereby the testator and two witnesses must appear on an audio-visual link at the same time. Through this link, the witnesses must be able to see the testator electronically sign the will. One of the witnesses must be an authorised witness such as an Australian legal practitioner, who will then need to certify that the will was witnessed in accordance with the state or territory legislation.

Australia also recognises 'informal wills' – that is, wills which do not comply with the legislative requirements determining validity, but which are nonetheless still deemed to be testamentary instruments. However, an application for grant of an informal will is costly without any guarantee that a grant will be issued. For example, courts have issued grants of representations on text message and other audio-visual wills. However, care should be taken where the requirements for a valid will are not complied with.

4.6 What best practices should be observed when drafting a will to ensure its validity?

When drafting a will, it is recommended to take instructions directly from the testator when the testator is alone. This is to assess his or her testamentary capacity to make a will and to avoid any undue influence or duress by other persons. The test as to whether a person has testamentary capacity is found in Banks v Goodfellow (1870) LR 5 QB 459, which requires the testator to:

- have a certain level of understanding in relation to his or her assets;

- comprehend the effect of making a will; and

- appreciate any claims that a person may have against the estate.

It is recommended to make a careful file note outlining:

- the testator's instructions;

- the professional's advice; and

- any overarching concerns.

If there are concerns about testamentary capacity, it is important to consider whether a medical opinion should be sought confirming that the testator has testamentary capacity.

4.7 Can a will be amended after the death of the testator?

In Australia, a will cannot be amended after the death of the testator. However, in certain circumstances, the disposition of assets can be modified if the beneficiaries consent and enter into a deed of family arrangement. That said, this may not provide the beneficiaries with tax exemptions and may trigger welfare gifting provisions.

Further, the disposition of assets can also be amended by an eligible applicant contesting the will. Any settlement or court order can amend the dispositions outlined in a will and may afford the new beneficiary or beneficiaries the necessary tax exemptions.

4.8 How are wills challenged in your jurisdiction?

Each state and territory has its own legislation enabling eligible applicants to make a claim for provision or further provision from a deceased estate. Generally, for an application to succeed, the following elements must be satisfied.

Eligible applicant: The following persons are generally considered to be eligible applicants Australia wide:

- a spouse or domestic partner of the deceased at time of death;

- a child, including a stepchild, of the deceased; and

- a person who was wholly or partially dependent on the deceased, to the extent the deceased had a moral obligation to provide for that person in the will.

Relevant considerations: A claim must generally be made within six months of grant of representation being issued by the court or 12 months of the date of death, depending on the state or territory in which the deceased was domiciled. When assessing the validity of a claim, the court will consider various factors, including:

- the terms of the deceased's will (if any);

- evidence of why the deceased drafted the will in a certain way; and

- any evidence as to the deceased's intentions in relation to provision for the applicant.

The court may also consider other factors, such as:

- the size of the estate;

- the relationship between the deceased and the applicant;

- the applicant's personal and financial circumstances;

- the circumstances of the other beneficiaries; and

- any other circumstances that the court sees fit.

Australian courts place a strong focus on whether the deceased had a moral obligation and the adequacy of any provision made. They also consider whether the applicant has a need for provision from the estate.

4.9 What intestacy rules apply in your jurisdiction? Can these rules be challenged?

If an individual dies intestate, each state and territory in Australia has laws that govern the distribution of assets to prescribed beneficiaries. Generally, if a person dies intestate, the following beneficiaries will be entitled to a share of the estate (in order of priority):

- a partner or partners of the deceased;

- children of the deceased;

- grandchildren of the deceased;

- parents of the deceased;

- siblings of the deceased;

- nieces and nephews of the deceased;

- grandparents of the deceased;

- aunts and uncles or cousins of the deceased; and

- the Crown.

The portion of the estate distributed between the beneficiaries varies according to the legislation of the state or territory in which the deceased was domiciled.

An eligible applicant can challenge the disposition of assets upon intestacy in the same manner as contesting a will.

5 Trusts

5.1 What laws govern trusts or equivalent instruments in your jurisdiction? Can trusts be governed by the laws of another jurisdiction?

Trusts are recognised in Australia. There is no Commonwealth legislation governing the establishment or proper administration of trusts; however, each state and territory has enacted its own laws dealing with the operation and management of trusts, which are similar in nature. The management and interpretation of trusts are also governed by common law in Australia.

A deed can expressly provide that:

- it will be governed by the laws of a particular jurisdiction; and

- all parties to the deed will be bound by the laws of that jurisdiction.

However, this will not necessarily be determinative of the issue. In ascertaining the applicable law, the following considerations are particularly relevant:

- the place of administration of the trust;

- the place where the assets of the trust are situated;

- the place of business or residence of the trustees; and

- the objects or purposes of the trust and the places where they are to be fulfilled.

5.2 How is any conflict of laws resolved?

If a conflict of law arises, the assets that form part of the trust should be classified – for example:

- what assets are personal property (movable property) or real property (immovable property);

- where the assets are located; and

- the domicile of the trustee.

The usual course of action in the case of real property is that the law of the location of the asset applies (lex situs). On the other hand, for personal property, the laws of the domicile of the trust will generally apply (lex domicilii).

5.3 What different types of structures are available and what are the advantages and disadvantages of each, from the private client perspective?

Trusts can be categorised as either:

- inter vivos trusts (established during the settlor's lifetime); or

- testamentary trusts (established upon death).

The advantages of testamentary trusts include the ability to distribute income to minor children which affords each child the tax-free threshold on income tax for each financial year. On the other hand, the distribution of income to minor beneficiaries from inter vivos trusts incurs punitive tax at a rate of 45%.

Inter vivos trusts can further be categorised as discretionary, fixed or hybrid (a combination of discretionary and fixed) trusts.

Discretionary trusts usually have multiple beneficiaries, with the trustee having discretion as to which one or more of those beneficiaries should benefit from the corpus or income of the trust. However, a trustee has no discretion in a fixed trust; instead, the beneficiaries' entitlements are pre-determined by the terms of the trust deed.

The advantages of discretionary trusts include the ability to have multiple beneficiaries to which income can be distributed, including eligible trusts and companies. However, the disadvantages include the difficulties in changing the beneficiaries, as this may lead to a resettlement. Resettlement results in an obligation to pay stamp duty and capital gains tax on all assets of the trust.

The advantages of fixed trusts include their use in business enterprises and the ability to transfer the units with minimal tax consequences. However, the disadvantages include the requirement to distribute the income/assets in fixed entitlements and the trustee's inability to minimise tax obligations by distributing to multiple beneficiaries.

Other benefits of trusts include protection from creditors, family law benefits and taxation benefits.

5.4 Are foreign trusts recognised in your jurisdiction? If so, what process is followed in this regard?

Trusts established under the laws of other jurisdictions are also recognised in Australia, which is a member of the Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on their Recognition.

5.5 How are trusts created and administered in your jurisdiction?

In Australia, the requirements to establish a valid and enforceable trust are relatively straightforward.

In most cases, a trust is established by a person, called the 'settlor', who pays an amount – known as a 'settled sum' – to the trustee. The trustee holds the settled sum on trust in accordance with the terms of the trust deed, for the benefit of the beneficiaries. Once the trust has been established, other assets can be transferred to the trustee or acquired by the trustee to be held under the terms of the same trust deed.

When a trust is formed, the trustee has legal ownership of the assets that form part of the trust, but the income and capital are held for the benefit of the beneficiaries. In discretionary trusts, the beneficiaries have no right to the assets, but the trustee usually has the power to nominate which one or more beneficiaries should benefit.

For a valid trust to be established, some formalities should be apparent, known as the 'three certainties'. These are:

- certainty of intention (or certainty of word);

- certainty of the subject matter of the trust; and

- certainty of the beneficiaries/objects.

While some forms of trust can arise from the circumstances (called 'resulting trusts' – these forms are essentially remedial in nature), most trusts are 'express trusts'. Express trusts are usually established pursuant to a deed of settlement.

The trustees' powers may be either:

- administrative – that is, powers that relate to the management of the trust; or

- dispositive – that is, powers relating to the beneficiaries' benefit.

The powers of the trustees to administer a trust effectively are generally contained in statute, supplemented or amended by the terms of the trust instrument.

5.6 What are the legal duties of trustees in your jurisdiction?

In Australia, trustees are fiduciaries and have various duties under statute, the common law and the trust instrument. Key duties include the following:

- to act honestly and in good faith;

- to comply with the terms of the trust deed;

- to exercise reasonable care, skill and caution in the administration of the trust and the investment of the trust assets;

- to keep accounts and, at all reasonable times and on request, to furnish any beneficiary with accounts;

- to consider all beneficiaries when considering distributions; and

- not to fetter their own discretion.

5.7 What tax regime applies to trusts in your jurisdiction? What implications does this have for settlors, trustees and beneficiaries?

Depending on the jurisdiction in which the trust was established in Australia, most states and territories require trusts to be 'stamped' by the relevant revenue office.

No additional tax regimes apply other than the normal income tax or trust tax surcharge. Income accumulated in trusts is taxed at a rate of 45%. However, trustees usually distribute income to the beneficiaries, at which point the beneficiaries pay tax on that income in accordance with their individual income tax rates.

The acquisition of trust assets may have stamp duty implications; and the sale of assets may have capital gains tax consequences for the trustee. Trusts also have various surcharges payable, such as a trust surcharge on land tax.

In Australia, once a trust has settled, the settlor generally has no other role in the operation of taxation of a trust.

5.8 What reporting requirements apply to trusts in your jurisdiction?

Each financial year, the trust must prepare financial statements and tax returns to lodge with the Australian Tax Office. Other than filing tax returns, there are no other reporting requirements in Australia.

5.9 What best practices should be observed in relation to the creation and administration of trusts?

The structure and mechanics of a trust can easily be misinterpreted by a trustee. It is best practice for a trustee to obtain advice from a solicitor who specialises in trust law. Simultaneously, a trustee should obtain accounting advice to understand the tax consequence of any proposed action which he or she intends to take. If a trustee takes any action without the requisite power in the trust deed, he or she may be in breach of trust, which can result in unwanted and protracted litigation.

6 Trends and predictions

6.1 How would you describe the current private client landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? Are any new developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms?

Marginal income tax rate changes: In the Federal Budget for 2019–2020, the government announced a plan to reduce the marginal income tax rate for low to middle-income earners.

The notable change will commence from 1 July 2024, when the 32.5% marginal tax rate bracket will be reduced to 30%, aligning it with the tax rates applicable to corporations.

For high-income earners, this provides an opportunity to improve the income streaming benefits of income generated via family discretionary trusts to those beneficiaries who fall within the middle-income tax bracket.

Electronic signing of wills and other documents: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal and state governments have enacted legislation to allow many legal documents to be signed electronically, provided that certain obligations are met. These documents include contracts, statutory declarations, court documents, financial documents and documents which require a qualified witness.

In most states and territories, wills can now be signed electronically in the presence of two witnesses. This is a significant departure from the previous position that a will must be signed with wet ink in the presence of two witnesses. Generally, the legislation in each respective jurisdiction requires that additional requirements be met to ensure that electronic signing by the testator and the witnesses has been completed correctly, including that one of the witnesses be an authorised witness such as a legal practitioner.

Foreign investment reform (FIRB) regime: In 2021, the federal government enacted changes to the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Cth) and the Foreign Acquisition and Takeovers Regulation 2015 (Cth). Among other things, the changes provide that an interest in securities, assets, a trust or Australian land that is acquired through a will by a beneficiary who is regarded as a 'foreign person' may be subject to review by the treasurer under the FIRB regime.

7 Tips and traps

7.1 What are your top tips for effective private client wealth management in your jurisdiction and what potential sticking points would you highlight?

One general tip is to have a good appreciation of the wealth structure and the interrelatedness between different entities and trusts. It is best practice to create a group structure chart and to keep proper records of any trust deeds, supplementary deeds, company searches, company constitutions and shareholder registers. When seeking advice from a private wealth specialist or tax advice from an accountant, it is prudent to provide such professionals with these documents to ensure that the advice aligns with the structure and the powers afforded to the trustee in the trust deed.

It is also recommended to diversify assets across trust structures and entities for additional asset protection, to avoid all assets being subject to any litigation or creditor claims from one single trust or entity.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.