TRANSFER OF DATA BY AUSTRALIAN ORGANISATIONS TO OTHER JURISDICTIONS IS INCREASINGLY COMMON.

This is a result of IT service providers using personnel and infrastructure in low cost jurisdictions such as India to service Australian based clients. The cloud computing industry alone is now worth nearly $2 billion in Australia and about half of this is spent on public cloud services. Eighty six per cent of Australian businesses now report that they use cloud services.1

While there are onshore data processing options available in the marketplace (including 'Australianonly' clouds2), these may not offer the customer the same benefits (e.g. economies of scale, affordability) as offshore options.

There are a range of commercial risk and regulatory considerations that any customer or supplier considering offshoring data needs to assess. In particular, new laws govern the 'disclosure' by Australian organisations3 of personal information4 to overseas recipients from 12 March 2014.5 This note addresses some of the relevant issues.

WHAT ARE THE CHANGES TO PRIVACY LAW?

The new law replaces the National Privacy Principles (that applied to private organisations) and Information Privacy Principles (that applied to government agencies) with a single list of principles called the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs).

The new law gives the Privacy Commissioner more powers, including:

- the ability to seek enforceable undertakings from organisations that have breached the Privacy Act and enforce any such undertaking in the courts;

- the power to initiate own motion investigations

- whether or not a complaint from an affected individual

- has been made; and

- the power to apply to the Federal Court for a civil penalty order of up to $1.7 million for serious or

- repeated breaches.

HOW DO THE APPS GOVERN 'DISCLOSURES' OVERSEAS?

APP 8 requires that before disclosing personal information to a person that is outside Australia (an overseas recipient), an Australian organisation must:

- take reasonable steps to make sure that the overseas recipient will not breach the APPs and the Australian organisation will be accountable for any such breach by the overseas recipient; or

- alternatively:

-

- make it known to the relevant individual that his or her personal information will not be protected by the APPs after the 'disclosure' to the overseas recipient and obtain the indvidual's consent to the 'disclosure'; or

- form a reasonable belief that the overseas recipient is subject to laws substantially similar to the APPs.

STEP ONE: IS THE DATA TRANSFER A 'DISCLOSURE'?

APP 8 does not apply unless the personal information is 'disclosed' to an overseas recipient.

Is the transfer a 'disclosure' or a 'use'?

The new law does not define what constitutes a 'disclosure'. The NPPs regulate cross-border 'transfers' of personal information, not 'disclosures'.6 Under the Explanatory Memorandum for the new law, Parliament explained that 'disclosure' isn't intended to be as broad as 'transfer'.7 The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines a disclosure as "the act of making something known". Accordingly, a transfer of personal information to an overseas recipient will not necessarily be a 'disclosure' or subject to APP 8.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) has suggested that a 'disclosure' occurs when information is released from an entity's effective control.8

In the context of cloud services, the OAIC is of the view that a transfer of personal information will not be a 'disclosure' if the service provider is only storing the data and certain contractual protections are implemented:

OAIC EXAMPLES9 |

|

Where an APP entity provides personal information to a cloud service provider located overseas for the limited purpose of performing the services of storing and ensuring the entity may access the personal information, this [will not be a 'disclosure'] provided:

|

However, the OAIC has also given guidance that the following service provider arrangements will involve a 'disclosure':

- outsourcing processing of online purchases through website to an overseas service provider (providing personal information on customers to the service provider in order to facilitate);

- sending information to an overseas service provider for the purposes of conducting reference checks on behalf of the Australian organisation; or

- an Australian organisation relying on a parent company offshore to supply billing support (providing the parent with access to its customer database in order to facilitate).

The distinction between the cloud storage example and the other examples given doesn't appear to be justified in terms of 'control'. For example, the online payment processing agreement could be subject to the same contractual controls as the OAIC stipulates in the cloud storage example. The distinction appears to be in the different levels of use or processing of the personal data required by the service provider in each example. In the cloud storage example, the service provider does not need to use, access or view the personal data, whereas in the other examples, the service provider does need to access or view the data in order to perform its services.

It is interesting that neither the new law, nor the OAIC guidance, deals with encryption of personal data in the context of APP 8. Arguably, if a customer encrypts personal information before providing it to its service provider, no 'disclosure' of the personal information will occur.

Even if an Australian organisation can satisfy itself that a transfer of personal information to an overseas recipient is not a 'disclosure' and therefore not subject to APP 8, the organisation may still be liable for any breach of the APPs by the overseas recipient on the basis that the overseas recipient is acting as the Australian organisation's agent and its acts or omissions may be taken to be acts or omissions of the Australian organisation for the purposes of the Privacy Act.

It is important to recognise that OAIC guidance10 in relation to 'disclosure' is not legally binding. However, prudent organisations will take note of the regulator's guidance when implementing compliance procedures.

Based on the Explanatory Memorandum for the new law, we can be confident that the following acts will constitute a 'disclosure':

- publishing personal information on the internet;

- accidentally releasing personal information publicly; and

- sending information to a related company (for

- example, a parent or sister company).11

Transferring personal information outside Australia: 'use' or 'disclosure'?

Further, a transfer of personal information within the same corporate entity is not considered a 'disclosure', even if that transfer is to an overseas office of the same entity.12

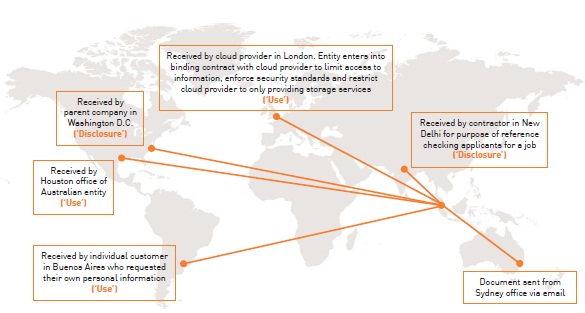

The diagram below is a visual representation of the acts that may constitute a 'disclosure' to an overseas recipient.

STEP TWO: 'REASONABLE STEP'S TO ENSURE THE SERVICE PROVIDER DOES NOT BREACH THE APPS

Assuming that a 'disclosure' has taken place and it is received by an overseas recipient, the consequence is that an Australian organisation must take reasonable steps to ensure that the overseas recipient does not breach the APPs.

Parliament has suggested that reasonable steps will normally require that an entity enter into a contractual relationship with the recipient.13

The OAIC has also gone a step further, specifying contractual conditions that it believes may be sufficient to satisfy the 'reasonable steps' requirement:

OAIC RECOMMENDED CONTRACTUAL PROPERTIES14 |

| Set out the types of personal information to be 'disclosed' and the specific purposes of 'disclosure'. |

Include obligation that overseas recipient complies with APPs

in relation to:

|

| Include obligation that subcontractors comply with same requirements as above. |

| Include requirement that overseas recipient implement a data breach response plan (for notifying Australian entity of data breaches and required remedial action). |

EXCEPTIONS

Exception 1: where consent is obtained

An entity will not need to ensure the overseas recipient complies with the APPs if the entity obtains consent from the individual whose information is being 'disclosed'. Consent will only be valid where it is (a) expressly obtained and (b) plainly evident that the individual was aware the entity would not be taking steps to ensure the overseas recipient complies with the APPs.15

The OAIC has suggested that valid consent will be given where:

- the entity provides a clear written or oral statement explaining the consequences of consent (i.e. the entity will not be accountable for breaches of the APPs by the foreign entity and the individual may not be able to seek redress); and

- the statement explains practical effects and risks associated with 'disclosure' that the entity is aware of (e.g. that the individual will not have the ability to access personal information relating to the individual that is held by the foreign entity).

Exception 2: where the overseas recipient is subject to substantially similar laws

An entity will not need to ensure the overseas recipient complies with the APPs if the entity has a reasonable belief that the person outside Australia is subject to laws substantially similar to the APPs.

What constitutes a reasonable belief?

A reasonable belief is more than merely a 'genuine or subjective belief'. The OAIC suggests that it is the responsibility of the organisation to justify its 'reasonable belief' if there is a dispute. One example that the OAIC gives is where an organisation has obtained independent legal advice on the foreign privacy protections.

What are substantially similar laws?

Laws which are substantially similar do not necessarily need to requote the protections in the APPs. Rather, the 'overall effect' of the law is the determining factor.

The OAIC hasn't been willing to disclose a "white list" of countries that it considers to have substantially similar laws to Australia, but the EU white list16 may be a good starting point for an analysis (the list includes, for example, Switzerland, Argentina and New Zealand). It is prudent to seek legal advice as to whether the country where an overseas recipient is located is subject to substantially similar laws. In the context of cloud computing, this may involve considering the laws of each of the jurisdictions in which the service provider's infrastructure is located.

The OAIC has published its own guidance as to what it will take into account when considering foreign privacy laws:

OAIC RECOMMENDED CONTRACTUAL PROPERTIES16 |

| Is there a comparable definition of 'personal information'? |

| Does it regulate collection of personal information in a similar way to the APPs? |

| Does it require the recipient to notify individuals about collection? |

| Does it require the recipient to use or 'disclose' personal information only for authorised purposes? |

| Are there comparable data quality and security standards? |

| Is there a right to access and seek correction of personal information? |

The last element is that the similar laws must have enforcement mechanisms that are accessible to an individual whose personal information is 'disclosed'. An equivalent body of the OAIC or courts with similar functions and powers will be a necessity.

Privacy Policy & Collection Statements

In addition to complying with APP 8, Australian organisations are required to include in their Privacy Policy:

- whether they are likely to 'disclose' information overseas17; and

- b. the countries where overseas recipients are located.18

If the information is likely to be 'disclosed' to a person overseas who is not already listed in the Privacy Policy, then an entity must send the individual a Collection Notice that lists the other countries where the information may be 'disclosed'.19

Security

Australian organisations are also required to take appropriate security measures to protect any personal information from misuse, interference and loss and from unauthorised access, modification or disclosure.20 Security may need to be more rigorous if the information is sensitive or the potential consequences for the individual, if the information were disclosed, are severe.

Other regulation

Depending on the industry the organisation is in or for government agencies, there are additional laws that may also apply to offshore data transfers.

Commonwealth Government agencies are subject to separate, stringent rules when they choose to outsource or offshore data (Attorney-General's Guidelines for Outsourced or Offshore ICT Arrangements). For example, where personal information is sent offshore or placed in a public cloud service arrangement, the agency must first obtain the consent of both the Attorney- General and the Minister responsible for the agency.

There are special data management requirements for financial institutions (APRA Prudential Practice Guide CPG 235). These include ensuring that all contracts for the outsourcing of data (not just personal information) include special conditions relating to the handling of that data. APRA suggests that these include terms covering business continuity management and that a risk assessment procedure be established before these arrangements can be entered into.

Footnotes

1IDC. 'Cloud is now business as

usual'. (16 July 2013).

2'Australia-only' cloud services are those

where the provider commits to only storing or processing data in

data centres located in Australia.

3T his includes entities with an 'Australian

link' in accordance with s 5B.

4T his is information or opinion about an identified

individual or a person who is reasonably identifiable. It does not

matter whether the information is true or actually recorded in a

material form.

5Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection)

Act 2012 (Cth).

6NPP 9 (Transborder data flows)

7Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection)

Bill 2012 – Explanatory Memorandum p 83

8OAIC Guidance (APP 8) at [8.8]

9OAIC Guidance (APP 8) at [8.14]

10OAIC Australian Privacy Principles Guidelines

(February 2014)

11OAIC Guidance (APP 8) at [8.13]

12Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection)

Bill 2012 – Explanatory Memorandum p 83

13Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection)

Bill 2012 – Explanatory Memorandum p 83

14OAIC Guidance (APP 8) at [8.16]

15Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection) Bill

2012 – Explanatory Memorandum p 84

16T he European Commission has published a "white

list" of countries that it considers has adequate data

protection laws (see: http://www.

privacycommission.be/en/transfers-outside-the-eu-with-adequate-protection)

17APP 1.4 (f)

18APP 1.4 (g)

19APP 5.2 (i) and 5.2 (j)

20APP 11.1

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

|

|

| Most awarded firm and Australian deal of

the year Australasian Legal Business Awards |

Employer of Choice for

Women Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace (EOWA) |