Thin capitalisation rules are established to prevent the over-indebtedness of companies who are usually structured in such a way for tax and commercial reasons. In this regard, a company is thinly capitalised when the companies capital is made up of a much greater proportion of debt than equity. In simpler words, it means that a company owes a bank, another company or a person, a significant amount of cash considering its equity position.

This raises two tax issues in an international context, both of which have been broadly used for tax planning:

- a) Interest due to the loan is remitted abroad with what may be a low tax rate in comparison to dividends or other ways of remitting funds abroad (profit shifting).

- b) Interest may be considered an accepted expense for the borrower so it decreases taxable profit and therefore taxation (tax base erosion).

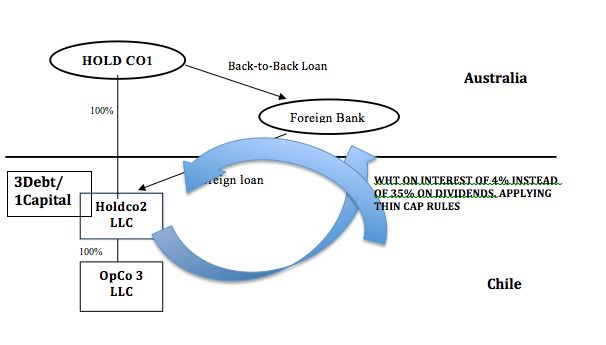

At one time, it was common to have what is known as back-to-back loans. This is where one person (the lender) lends money to the other (the intermediary) who lends a similar amount of money to a third person (the borrower). There does not need to be an agreement between the lender and the borrower because each is dealing separately with the intermediary. The credit provided to the borrower might be secured by the deposit made by the lender to the intermediary. The borrower might be paying interest to the intermediary who might be paying a slightly smaller amount of interest to the lender. Usually, the lender and borrower are in separate countries, and the intermediary might be in a third country.

This type of tax planning is based on repatriating funds back to the HoldCo with a preferential withholding tax rate on interest instead of the withholding tax rate of dividends that is usually higher. In addition, the interest paid abroad may be used in some cases as an expense that will decrease the taxation of the operating company.

In Chile, under general rules, interest on loans granted by foreign non-resident entities is subject in Chile to a 35% withholding tax on the amount paid abroad or credited to account.

However, when the loan is granted by a foreign / international bank or financial institution, the interest rate is 4% on the amount paid or credited to account.

According to Chilean thin capitalisation rules, interest on the excess borrowing is subject to 35% if the loan is considered related and there is an excess of borrowing or a lack of capitalisation.

Related borrowing is understood to exist in the following cases:

- When the lender directly or indirectly owns or participates in 10% or more of the capital or profits of the borrower.

- When borrower and lender are owned by a common shareholder that directly or indirectly owns or participates in 10% or more of the capital or profits of both.

- When the lender is incorporated or resident in a jurisdiction considered as a tax haven, and it is contained in the list issued by the Ministry of Finance.

- When the financing has been granted with direct or indirect guarantee from a third party in cash or valuables representing cash obligations, up to the amount effectively guaranteed in such a manner.

In addition, excess borrowing or thin capitalisation is understood to exist when the total borrowing exceeds three times the borrower's equity for the year that the loan was granted.

Notwithstanding, the actual determination of the ratio requires a calculation based on the relevant facts and figures, even more so with the recent tax reforms in Chile.

The above thin capitalisation rules apply even when a Double Tax Treaty is involved, as the thin cap surtax (31%) befalls on the borrower and not on the foreign lender. The Chilean IRS has confirmed this position determining that thin cap norms overrule whatever preferential tax rate the DTA may be on interests.

Thin cap rules have been consistently tougher for taxpayers. Indeed, pursuant to the Chilean Tax Reform there are several rules that are more demanding:

- The ratio debt/equity 3:1 is now more challenging. There are more concepts that go into debt, such as debt with local residents, which was not considered debt before. It is therefore harder to fulfil the ratio (they are not so thin anymore).

- The ratio is calculated now on an annual basis. Before the tax reform, the taxpayer had to fulfil the ratio 3:1 only on the year the loan was granted. If repayment took place for the next ten years, in the remaining time the taxpayer would have the benefit of only a 4% WHT rate on interest instead of the usual 35%. Now, taxpayers have to check the ratio annually and will probably have to make capital infusions or capitalizations to achieve the 3:1 ratio on some given years.

In conclusion, structuring foreign investment through debt is a useful manner of minimising the tax burden for companies. It allows the lender to recollect payment at whatever agreed upon timeframe in spite of the financial situation that the operating company may be in.

Lastly, foreign investors will have to consider that foreign loans, whether provided through documents or not, pay stamp tax duty. In effect, documented loans and undocumented foreign loans are subject to stamp tax duty at 0,066% of their value each month (or fraction of month) between disbursement and maturity, with a cap of 0,8% (0,066 *12). Loans to be paid over a period of a year are therefore levied with this maximum rate. This tax is imposed on the loan principal (interest are levied apart) indicated in the document. For loans with no maturity date and are payable on-demand, the tax hikes up to 0,332%.

These new higher tax rates have been in force since January 1st 2016 and are another issue to take into account when structuring loans between companies.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.