"Health and well-being" is on the Government's radar. Two recent publications, a housing design audit by University College London (UCL) and a Department for Transport survey, prompt consideration of the role that the planning process in England plays in ensuring the health and well-being of the people who live and work in this country. In a blog post last year we looked at well-being in the built environment and the Well Building Standard. How else can planning influence the choices that we can make to improve our health and well-being?

What do we mean by health and well-being?

Dictionary definitions vary but the following definitions seem most apt:

HEALTH – the condition of the body or mind and the degree to which it is free from illness, or the state of being well

WELL-BEING – a good or satisfactory condition of existence; a state characterized by health, happiness, and prosperity

Clearly there's a large degree of overlap. With regard to how we achieve either or both, it has been recognised for many years that it is better to encourage and facilitate healthy lifestyles proactively than to wait to treat ill health – prevention is better than cure.

The role of planning

According to Dan Buettner, author of several books on the Blue Zones (regions around the world where people live much longer than average), the secret to creating happier people and places lies in optimizing the environment in which we live. The planning process can play a key role in doing just that.

In a paper for the 2019 Joint Planning Law Conference in Oxford, Professor Sir Malcom Grant stated that:

"...in general, where and how people live has a significant impact on their mental and physical health, and the planning system as a powerful regulatory model has a potentially significant contribution to make to the health of the population."

Historically, however, the planning system has not realised its potential to make such a positive contribution. Back in February 2010, the Marmot Review found that:

"At present, the planning process at local and national levels is not systematically concerned with impact on health and health equity" and "the lack of attention paid to health and health inequalities in the planning process can lead to unintended and negative consequences."

It appears that there is still a lot of room for improvement. According to Public Health England, people in the least deprived parts of England live, on average, 19 more years in good health than people in the most deprived parts. One potential reason for the disparity was highlighted by the housing design audit for England carried out by UCL published this week, which revealed that 75% of new housing development surveyed should not have gone ahead due to "mediocre" or "poor" design and that less affluent communities are ten times more likely to get more poorly designed housing.

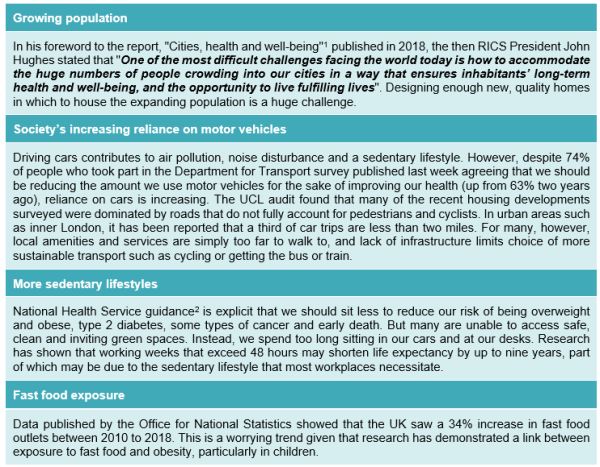

Why has it been so difficult for the planning process to bring about positive changes to the environment in which we live? In part it has been due to the evolving challenges that society has faced in recent decades and the pace at which planning policy and development has needed to adapt to tackle those challenges. Set out below are some (but far from all) of the key challenges.

More needs to be done to improve the number and design of new housing and offices, promote sustainable development that relies less on cars, create access to green outdoor spaces (and maybe even outdoor gyms) and reverse the trend for more fast food outlets. Planning Practice Guidance shows how good planning can play a part in this: "Healthy and safe communities" contains guidance for public health organisations, health service organisations, commissioners, providers and local communities to help them work effectively with local planning authorities to promote healthy and inclusive communities and support appropriate health infrastructure. However, proactive, positive steps need to be taken to translate the helpful guidance into action that makes a noticeable difference to people's lives.

How much control over this do individuals have? Through participating in consultations on planning policy and guidance and proposed new developments we can all play a role, particularly in terms of the likely health and well-being impacts that may result from, for example, the number of parking spaces, provision of cycle paths and stands, access to public transport, access to open space and the design of workplaces.

In conclusion, the planning system alone can't solve all our health and well-being problems, but it's a good place to start.

Footnotes

1 https://www.rics.org/globalassets/rics-website/media/knowledge/research/insights/cities-health-and-well-being-rics.pdf

2 https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/why-sitting-too-much-is-bad-for-us/

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.