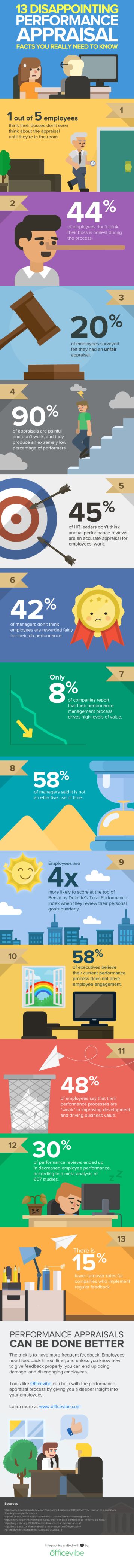

If there is any common ground between employees and employers, it is that both of them usually hate annual performance reviews. A survey found that "90% of appraisals are painful", and 58% of managers found that performance reviews are not an effective use of their time.

Consulting multinational Accenture recently announced that it will be getting rid of annual performance reviews and rankings. Starting September 2015, Accenture will change the way it reviews its employees' performance and will start focusing on ensuring employees receive timely feedback from their managers on an ongoing basis. Accenture is following the steps of companies like Deloitte, Adobe, Gap and Microsoft who have started to adopt less conventional approaches to performance management.

Deloitte for example, has done away with lengthy performance evaluations and reduced it to 4 simple questions, the first two are answered on a five-point scale from "Strongly agree" to "strongly disagree", and the last two questions can be answered with a simple "yes" or "no":

- Given what I know of this person's performance, and if it were my money, I would award this person the highest possible compensation increase and bonus.

- Given what I know of this person's performance, I would always want him or her on my team.

- This person is at risk for low performance.

- This person is ready for promotion today.

How do such novel approaches to performance management fit into the context of Malaysian employment law?

Malaysian law doesn't require employees to adopt a specific approach to employee management. A popular myth is that there is a requirement for employers to give "3 written warnings" to an employee before there can be a termination for poor performance. There is in fact, no such legal requirement. The Employment Act is silent on what amounts to justifiable termination for poor performance, and Malaysian case law have only set out 3 broad requirements:

- the employee must have been warned about his poor performance

- the employee must have been accorded sufficient opportunity to improve; and

- notwithstanding the above, the employee failed to sufficiently improve his performance

A properly structured performance appraisal system will ensure that all 3 requirements are met in the event there is an unfortunate decision to terminate an employee. As part of procedural fairness, employees must always be made aware if they are not meeting their superior's expectations. The requirement for a "warning" could be a misnomer as there is no legal requirement to issue a formal warning letter, or provide a minimum number of warnings. The essence of the requirement is that the employer must highlight the weak areas of the employee's performance, the employer's dissatisfaction with the employee's performance, and a time frame for the employee to improve on those areas.

Since what amounts to "poor performance" differs depending on the individual employee, the expectations of the employer, the job scope and other factors, there is no "legal" definition of "poor performance". In a decided case, the Industrial Court held:

"Though the judgment or opinion of the superiors deserve consideration in a case of dismissal for poor performance, they are not of much evidentiary value unless they are supported by objective evidence. Any superior can testify that in his opinion or judgment, an employee has performed poorly."

What is consistent is that if an employer wants to allege that an employee is a poor performer, it needs to have evidence to prove it. The performance review process can be as short or long or progressive as employers want it to be – but at the end of the day, employers need to ensure that their opinion and assessment of employees are properly documented and justified.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.