Overview

In many open market transactions, considerable emphasis is placed on attempting to establish the ‘correct value’ of an acquisition target. However, the valuation of a business is a subjective exercise. Business values can change considerably based on assumptions regarding future cash flows, discount rates, growth rates, and so on. Therefore, while an objective assessment of business value based on sound methodologies and principles is important, a purchaser should be cognizant of the underlying ‘economic drivers’ that influence the value of a particular business.

This will allow the purchaser to structure a transaction in a way that will reduce the risk of ‘overpaying’ for an acquisition target in circumstances where the returns (cash flows) arising from an acquisition do not materialize to the extent anticipated. By matching the risks and rewards associated with an acquisition (to the extent practical), the purchaser is employing a ‘value-based pricing strategy’.

This paper begins with a discussion of the components of value and price, including how purchasers normally determine the value of an acquisition target. Given this foundation, the paper then addresses how a ‘value-based pricing’ transaction structure can be developed. This includes an examination of how a purchaser can use alternate forms of consideration and other aspects of the deal to reduce the risks inherent in a particular acquisition. The paper concludes with a discussion of specific considerations for public-entity purchasers in terms of financial reporting implications arising from corporate acquisitions.

The Determinants of Value and Price

The principal determinants of the ‘value’ (normally defined as ‘fair market value’) of a particular business are the:

- cash flows that a business prospectively is expected to generate. In this regard, cash flows normally are defined as ‘discretionary cash flows’, determined net of capital expenditures, working capital requirements, and income taxes1; and

- rate of return (normally defined as a ‘discount rate’ or ‘capitalization rate’) applied against those cash flows, which rate reflects the time value of money as well as the opportunities and risks of a particular business and the industry in which it operates.

Cash flows and rates of return are directly interrelated. All things equal, more optimistic cash flow projections command a higher rate of return (or a lower multiple, being the inverse of the rate of return) in order to reflect the higher level of risk involved. As a simplistic example, if a business was expected to generate discretionary cash flows of $1 million per annum, and assuming that a 10% rate of return (‘capitalization rate’) was considered appropriate, then the ‘value’ of the business would be calculated at $10 million (being $1 million divided by 10%). Furthermore, if $10 million were believed to be the ‘correct’ value of the business, that figure could also be arrived at assuming annual cash flows of $1.2 million with a 12% capitalization rate, or $900,000 with a 9% capitalization rate, or an infinite number of other combinations.

It is important to note that the ‘value’ of a business as calculated by the purchaser or the vendor may be considerably different that the ‘price’ that will be paid for that business in an open market transaction. Open market prices are influenced by factors such as the forms of payment used, the negotiating position and abilities of the parties involved, and numerous other factors that may only come to light when the business is exposed for sale in the open market. That said, a purchaser normally begins by estimating the ‘value’ of an acquisition target to it, and then making adjustments to that value to reflect such things as the:

- terms of the transactions, including the forms of payment that will be offered;

- perceived importance of the acquisition target to the purchaser, including alternatives available to it;

- purchaser’s perception of its negotiating position relative to that of the vendor; and

- post-acquisition synergies that are believed to be available to the purchaser, the likelihood that such synergies will be realized, and the extent to which the purchaser perceives such synergies would be available to other interested parties.

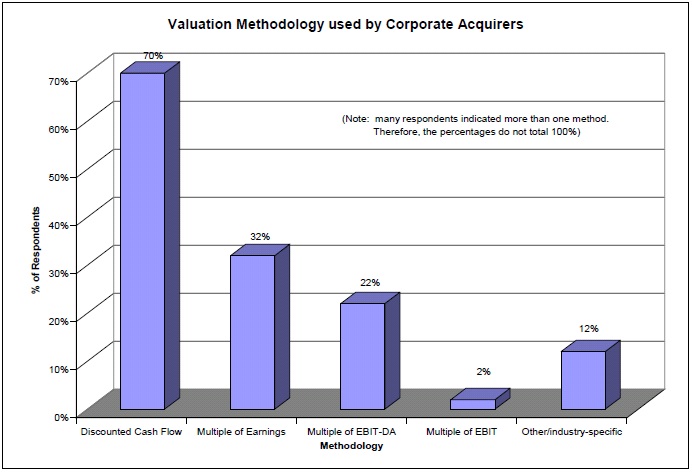

When determining the ‘value’ of an acquisition target, a purchaser normally adopts a ‘discounted cash flow’ (‘DCF’) valuation methodology, as illustrated in the chart below2. Assuming that credible financial projections exist, the DCF methodology typically is the most conceptually sound approach as it considers prospective operating results of the acquisition target on an annual basis, and the required rate of return given the risks embedded in those cash flows.

In many cases, the valuation conclusions arrived at pursuant to a DCF methodology are ‘tested’ against ‘comparable company transactions’ that have occurred in recent years involving businesses whose operations are believed to be similar to those of the target company. For example, ‘multiples’ of trailing EBIT-DA (‘earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization’) imputed from the DCF value conclusions are compared to similar EBIT-DA multiples observed in recent open market transactions involving ‘comparable’ companies in the same industry.

The difficulty encountered when examining comparable company transaction multiples stems from the limited availability of important information regarding the particulars of the transaction that may have significantly influenced the observed multiples. Every transaction is unique, and without the benefit of direct involvement in a particular open market transaction it typically is not possible to assess such things as the:

- impact the terms of the deal had on the price that ultimately was paid;

- relative negotiating strength and negotiating ability of the purchaser and the vendor; and

- extent to which the purchaser perceives that post-acquisition synergies may be available, and the extent to which those synergies were ‘paid for’.

As a result, while multiples observed in recent open market transactions may be considered in the context of a particular acquisition exercise, over-reliance on such an approach may be detrimental to the purchaser, the vendor, or both.

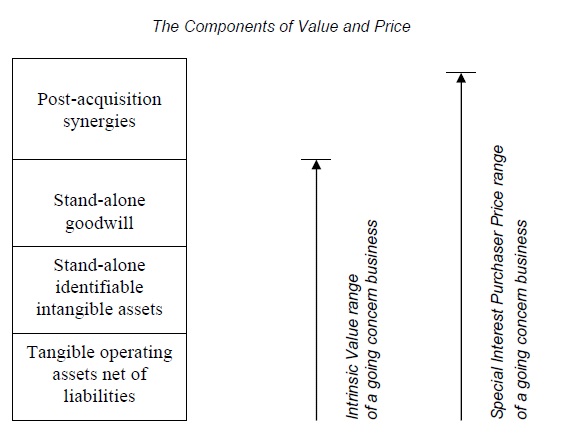

When dealing with 100% of the outstanding shares or net assets of a business that is valued on the assumption that it will continue to operate as a going concern, and post-acquisition synergies are expected, the two possible components that comprise any given open market price are:

- that reflective of the value of all of the outstanding shares or net operating assets of the business viewed on a stand-alone basis. That is, the value of the business interest assuming the business will continue to operate ‘as is’, absent a divestiture of all or part of it. This value component often is referred to as intrinsic value. Intrinsic value is comprised of three distinct components where the business is viewed on a stand-alone basis. These are:

- tangible operating assets, net of liabilities, required to carry on the business,

- identifiable intangible assets (if any), which may include brand names, patents, copyrights, franchise agreements, trademarks, and so on, and

- where applicable, goodwill, being the aggregation of non-identifiable (or ‘non-specific’) intangible assets, and identifiable intangible assets not otherwise accounted for; and

- an incremental value over intrinsic value perceived by a purchaser at the time of acquisition comprised of post-acquisition synergies and/or strategic advantages (collectively referred to hereafter simply as ‘synergies’). The quantification of this incremental value is unique to each potential purchaser. Examples include incremental revenue opportunities, cost savings and overall risk reduction that the purchaser expects will result from combining the acquired business with its existing operations. Purchasers who anticipate synergies often are referred to as ‘special interest purchasers’. The combination of intrinsic value and post-acquisition synergies sometimes is referred to as 'Special Interest Purchaser Price’.

The components of 'intrinsic value' and 'Special Interest Purchaser Price' are summarized in the chart below.

Although the tangible assets of a business often can be valued separately, it is considerably more difficult to assess the value of a particular intangible operating asset. Further, the value of goodwill can rarely be quantified in isolation. Traditionally, when reference was made to the specific amount of goodwill inherent in a business, that amount normally was derived by deducting the estimated ‘value in use’ of the net tangible assets from overall ‘going concern value’. Stated differently, in practice values for intangibles and goodwill seldom were segregated, but rather were aggregated and together referred to as ‘goodwill’ or generic ‘intangible value’. This practice may change pursuant to newly introduced accounting standards in the U.S. and Canada regarding ‘Goodwill and other Intangible Assets’ which require certain intangible assets be separately quantified for accounting purposes (see discussion under ‘Public Entity Purchasers’).

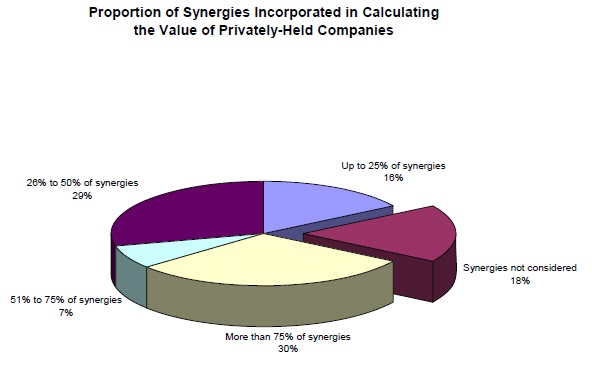

The quantification of post-acquisition synergies generally should be a separate and distinct component of any business valuation or pricing exercise. Accordingly, the intrinsic value of the business should be estimated as the ‘base value’ and the value of synergies should be added to that base where applicable. This segregation not only assists in evaluating the reasonableness of the components, but in an open market transaction enables the purchaser separately to consider the portion of the anticipated synergies it wants to ‘pay for’ in its pricing strategy. Where a purchaser does not pay for expected synergies, these serve to compensate for unanticipated shortfalls from expected post-acquisition discretionary cash flows. No acquisition review can be so complete as to eliminate all post-acquisition surprises. In many instances, a lower level of post-acquisition benefits and a higher level of costs materialize following acquisition than were anticipated during negotiations. Consequently, if the value-added component is fully paid for, the purchaser has eliminated all downside protection and the likelihood of acquisition success is reduced.

A proper quantification of post-acquisition synergies requires a balanced, realistic perspective of the potential benefits to be derived from the acquisition, as well as an assessment of the likely incremental costs to be incurred in their realization. A discussion of the quantification of synergies is beyond the scope of this paper3. In most open market transactions involving medium and large sized businesses, one or more purchasers perceive the ability to realize post-acquisition synergies. It is unusual for a vendor to be paid fully for all purchaser-perceived post-acquisition net economic benefits. As indicated in the chart below4, while corporate acquirers normally consider the benefits of post-acquisition synergies when assessing the value of an acquisition target, in most cases only a portion of those synergies are ‘paid for’.

Value-Based Pricing Strategy

The determination of ‘value’ pursuant to a DCF methodology (or other valuation methodology) normally represents a ‘cash equivalent’ price. Few deals are consummated in cash on closing.

As a minimum, purchasers normally insist on retaining a portion of the purchase price for a specified period of time in the form of a holdback to offset certain risks such as undisclosed liabilities that existed at the transaction date.

When structuring a transaction, purchasers sometimes use forms of payment other than cash and holdbacks, including vendor take-backs, share exchanges, and earn-out arrangements.

Furthermore, the terms of the deal may incorporate other important elements such as fact-specific vendor representations and warranties, non-competition agreements, and management contracts.

All of these things serve to shift the risks and rewards of the transaction between the purchaser and the vendor, and as such, they can have a significant influence on the price that ultimately is paid. Understanding the ‘value dynamics’ of the various forms of consideration and the terms of the deal is essential to the development of a ‘value-based pricing strategy’.

From the standpoint of a purchaser, the essence of a value-based pricing strategy involves matching (to the extent practical) the risk and reward dynamics of an acquisition with the terms of the deal and the forms of payment that are used. This requires an understanding of the:

- underlying determinants of business value and price (see previous discussion);

- risks inherent in a particular acquisition; and

- value parameters of the terms of the deal and forms of consideration.

A purchaser normally views acquisition risk as the failure of an acquired entity to generate sufficient post-transaction cash flows to provide it with a rate of return that is equal to or greater than its cost of capital when measured against the purchase price. An acquisition that generates a rate of return below a purchaser’s cost of capital results in an erosion of shareholder value. A shortfall in cash flows following an acquisition may be due to such things as:

- unanticipated cash outflows needed to shore up aging or inadequate capital equipment that was not detected during the due diligence phase, or to compensate for a deficiency in working capital where the assets acquired are not realized on a timely basis, or where ‘hidden’ liabilities are uncovered;

- revenues generated following the transaction are less than expected. Revenue shortfalls tend to be more common where sales growth had been anticipated (based on the expectation of increased market share, new customers, and so on) as opposed to the existing (or ‘baseline’) revenues of the business;

- higher operating costs than anticipated due to (for example) the need to add employees or cost infrastructure to support the existing operations of the business, or those required in order to achieve sales growth expectations;

- higher financing costs due to increasing interest rates where a portion of the purchase price was financed with floating-rate debt; and

- the failure to realize post-acquisition synergies to the extent anticipated.

In order to help offset these risks, purchasers may be able to ‘match’ the risk/reward parameters of the acquisition with the payoff from various forms of consideration. That is, the ‘cost’ of the various forms of consideration used (and hence the acquisition price) should increase where the returns are realized by the purchaser, and should decrease where post-acquisition returns are less than anticipated. For example:

- holdbacks and vendor take-backs can be used to offset some of the risk that the underlying tangible assets acquired are not realized to the extent anticipated (e.g. accounts receivable), or where ‘hidden liabilities’ are uncovered following the transaction;

- where a share for share exchange is used, and where the vendor will own a meaningful percentage of the consolidated operations following the transaction, it may be possible to ‘match’ some of the intangible value components. From the standpoint of a public entity purchaser, the ‘pay-off’ from intangible value (such as brand names, customer lists, goodwill, and so on) generally is realized in the form of the multiples applied to the reported operating results of the consolidated entity by the public equity markets (hence influencing its share price). By matching the value components of the purchaser’s (publicly traded) shares, and the vendor’s (public or private) shares, the purchaser will cause the vendor’s interests to be aligned with its own, as the vendor will participate in the upside (or suffer the consequences of the downside) where the market perceives that intangible values are increasing (decreasing); and

- earn-out structures are sometimes used where a large component of the total price paid is attributable to the growth prospects of the business, or where substantial post-acquisition synergies are anticipated. An earn-out effectively transfers the risk of non-performance from the purchaser to the vendor given that the price is reduced if anticipated results are not realized. Where the purchaser pays for the earn-out component, it normally does so with resources that it has already realized through the acquisition.

In addition to the various forms of consideration, other aspects of the deal can be structured so as to offset acquisition risks assumed by the purchaser. For example, where possible the purchaser should obtain:

- fact-specific vendor representations and warranties that serve to protect the underlying net asset base being acquired against unforeseen liabilities. However, vendor representations and warranties should not be relied upon by a purchaser as a substitute for adequate due diligence;

- a non-competition agreement from the vendor so as to protect the intrinsic value of the acquired business’ intangible assets, such as its customer base, technology, key employees, and so on; and

- management contracts that provide the vendor with upside potential where it helps to generate post-acquisition revenue growth and synergy realization in the acquired business, which things will accrue to the benefit of the purchaser.

While in theory a value-based pricing structure may be desirable, it is not always possible to implement in practice. Open market transactions are influenced by a myriad of factors, including the expectations of purchasers and vendors and the alternatives available to each. In addition, the dynamics of the negotiations will influence the price paid and the terms of the deal. The likelihood that a purchaser can achieve a value-based pricing structure increases where the:

- vendor’s negotiating position is relatively weak compared to that of the purchaser, due to the absence of attractive alternatives for the vendor; and

- purchaser’s negotiating abilities are strong, and it can effectively convey to the vendor the benefits and attractiveness of a deal that adopts a ‘value-based pricing’ concept.

It is unfortunate that, in many cases, the quantitative mechanics of a transaction overshadow the importance of negotiation skills, which are essential in structuring a transaction that makes sound economic sense, and that is viewed by all parties to be a fair and reasonable arrangement.

Public Entity Purchasers

Transactions undertaken by companies whose securities are publicly traded undergo greater scrutiny by investors and the market as a whole. While prospective cash flow remains the key economic driver, public entities typically are concerned with how a particular transaction will influence their prospective earnings per share. This is because the ‘price-earnings ratio’ generally remains an important determinant of the trading price of publicly held securities. Public entity acquirers usually are apprehensive about undertaking an acquisition that will result in a near-term dilution in their earnings per share, even if the transaction is economically sound. Accounting rules tend to have an influence on both the price that public company purchasers are prepared to pay for a particular acquisition target, as well as how the transaction is structured.

Effective January 2002, new accounting regulations were introduced in both the U.S. and Canada pertaining to business combinations, goodwill, and intangible assets. While a comprehensive discussion of these regulations is beyond the scope of this paper, some of the more important changes are:

- the ‘purchase method’ of accounting must be used to consolidate subsidiary companies, as opposed to the ‘pooling of interests method’, which is no longer permitted5. The ‘pooling of interests’ method was popular because it allowed a purchaser to avoid having to recognize goodwill amortization and higher depreciation following an acquisition, which costs would otherwise contribute to an erosion of consolidated earnings per share;

- goodwill created pursuant to a transaction (being the difference between the total purchase price and the ‘fair value’ of the tangible and identifiable intangible assets acquired, net of liabilities assumed) no longer has to be amortized for accounting purposes. Previously, goodwill was amortized over a period of up to 40 years, which served to reduce consolidated earnings per share following the transaction. While the amortization of goodwill is no longer necessary, the new accounting rules require an annual ‘goodwill impairment test’ to determine whether the goodwill of the acquired business still exists. If it does not, the amount of ‘impairment’ is charged to earnings in the current period; and

- certain intangible assets acquired must be segregated for accounting purposes. Such intangibles generally are defined as are those that arise from contractual or legal rights, or those that are capable of being segregated from the business and sold. Intangibles that meet the prescribed definition must be amortized over their expected lives, which in some cases may be short-lived. Depending on the nature and extent of such intangibles, a purchaser may have to recognize substantial amortization expense in the years following the acquisition. All other intangibles are not segregated for accounting purposes, and are classified as part of ‘goodwill’ – which is not amortized (as discussed above).

As a result of these (and other) changes, many public entity acquirers will seek to ‘manage’ their financial statements by structuring transactions in a way that allows them to report favourable consolidated earnings per share. Unfortunately, the structure of a transaction designed based on financial accounting regulations is not necessarily consistent with a structure developed based on sound underlying economic fundamentals.

Finally, public entity acquirers also should consider the nature and extent of their disclosure of acquisitions, both in the notes to the financial statements as well as in the ‘management discussion and analysis’ (‘MD&A’) section of the annual report, which typically precedes the financial statements. Formal accounting regulation disclosure requirements relating to acquisitions are relatively superficial in both the U.S. and Canada. As a result, purchasers often are able to ‘bury’ important (or possibly damaging) information about the transactions that they have undertaken. Companies in the U.S. that are subject to S.E.C. regulations are less able to take advantage of this due to the supplementary disclosure requirements designed to keep investors more informed.

The contents of MD&A essentially are unregulated today, although several professional bodies have published guidelines on what they believe should (or should not) be included. Management often takes advantage of MD&A disclosures since it is loosely regulated, and many investors afford it equal (or perhaps greater) weight than the audited financial statements. In light of the potential for investors to be mislead (either intentionally or unintentionally) regarding the costs and expected benefits of an acquisition due to the contents of MD&A disclosure, it is possible that this area will become more regulated in the coming years.

Conclusions

Business values are driven by prospective cash flows and rates or return. Purchasers normally estimate the value of an acquisition target pursuant to a DCF valuation methodology, supplemented with some consideration of ‘comparable company transactions’. Embedded in the overall value conclusion is a component of underlying net tangible assets, the intangible assets of a business including its ‘stand-alone’ goodwill, and post acquisition synergies. The determination of synergies normally is a separate element of the valuation process. In addition, the degree to which a purchaser ‘pays for’ synergies normally is discounted in light of the risks inherent in their realization.

Purchasers sometimes use various forms of consideration to consummate a transaction, including holdbacks, vendor take-backs, share exchanges, and earn-outs, in addition to (or in lieu of) cash at closing. Understanding the value dynamics of alternate forms of consideration is fundamental to developing a value-based pricing strategy. In essence, purchasers should attempt to align the risk and reward parameters of the acquisition target with the risks and reward parameters of the forms of consideration. Such ‘matching’ can also be done with other aspects of the transaction, including fact-specific vendor representations and warranties, non-competition agreements, and management contracts. By developing a ‘value-based pricing’ strategy, corporate acquirers will be more likely to ‘pay for value realized’, and increase the likelihood that an acquisition will generate an adequate rate of return measured in terms of its post-acquisition cash flows against the purchase price.

Implementing a value-based pricing strategy not only requires an understanding of the economic variables in an acquisition, but also a favourable negotiating position and sound negotiating abilities that can be used to create a win-win scenario.

Finally, when structuring a transaction, public entity purchasers typically are concerned with how the transaction will be reflected from a financial reporting standpoint, given the potential impact of such things on the market price of their shares following the transaction. New accounting rules recently introduced in the U.S. and Canada likely will have an influence on transaction structuring for public entity purchasers, and on the prices that they are willing to pay.

Footnotes

1 Discretionary cash flow normally is determined before debt servicing costs (interest and principal repayment). The costs and benefits of financing normally are incorporated in the rate of return applied to the discretionary cash flows.

2 Source: A Survey of Corporate Acquirers, April 1999, Campbell Valuation Partners Limited. A complete copy of the study is available at www.cvpl.com.

3 An extensive discussion of the quantification of synergies can be found in The Valuation of Business Interests, Ian R. Campbell, Howard E. Johnson, Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, 2001.

4 Source: A Survey of Corporate Acquirers, Campbell Valuation Partners Limited, April 1999.

5 This change will have a greater impact on U.S. companies, which were more readily able to adopt the Pooling of Interests method as contrasted to Canadian companies where the accounting rules governing the use of the Pooling of Interests method were more stringent.