We have previously discussed the pros and cons of buying assets vs. shares from the standpoint of the buyer. To summarize; while a buyer normally prefers an asset deal in order to enjoy the related tax benefits, such benefits can vary widely depending on the nature of the assets acquired. While an asset deal affords the buyer less risk from a hidden liability perspective, it has to be weighed against the risks of renegotiating key contracts with customers and employee transition. The merits of a share deal vs. an asset deal from the seller’s perspective also involve tax considerations, as well as other factors, as discussed below.

Tax Impact

Sellers generally prefer to sell shares so that the proceeds enjoy capital gains tax treatment. In addition, the sale of shares can allow the seller to utilize their lifetime capital gains exemption of $750,000 per individual. This exemption can be multiplied over several family members if proper tax structuring is in place, which includes a two-year holding period for the shares. Therefore, it’s good tax planning for business owners to undertake an estate freeze well before the sale process is underway. This normally requires a formal valuation report prepared by a qualified Chartered Business Valuator.

For smaller size deals (i.e. those with sale proceeds of less than $5 million), the benefit of the capital gains exemption usually makes a share sale more economically attractive. However, the answer is not as straightforward for larger deals. Similar to the analysis on the buy-side, the tax consequences to the sellers resulting from an asset sale depends on the allocation of the purchase price among the tangible and intangible assets that are acquired. Specifically, where proceeds are allocated to depreciable capital property (e.g. equipment and vehicles), it can result in “recaptured depreciation” for income tax purposes, which is taxed at the top marginal rate for the business. Furthermore, there is a second level of taxation when the sellers withdraw money from the company. This can result in a significant tax burden on the sale of assets.

However, where the proceeds are allocated to “goodwill”, the tax impact is significantly less. This is because, for private companies, 50% of the proceeds allocated to goodwill flow through the “capital dividend account”, which can be paid out to shareholders tax-free. The other 50% of goodwill is subject to income tax at the company’s regular business rates. While the net proceeds on the taxable portion of goodwill are subject to personal income tax when the funds are withdrawn from the company, such taxes can be deferred if the remaining proceeds are left within the shell company, where they can be used by the sellers for other investments.

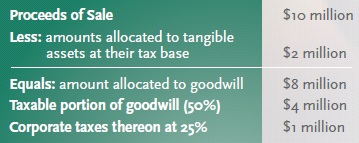

The following example serves to illustrate. Assume that the selling price for the net assets of a business is $10 million. The proceeds of sale are allocated as $2 million to working capital and fixed assets, at their respective tax bases, and therefore no immediate tax consequences arise. The remaining $8 million is allocated to goodwill. Assuming that the corporate tax rate for the business is 25%, the resultant income taxes at the corporate level are calculated as follows:

Therefore, of the $10 million of total proceeds, corporate taxes are only $1 million (or 10%). The non-taxable portion of goodwill ($4 million) can be immediately paid out to the shareholders without incurring any incremental personal taxes. That leaves $5 million in the business (being the $10 million of total proceeds less $1 million of corporate tax, less $4 million of tax-free dividends). When that $5 million is withdrawn from the company in the form of a taxable dividend, the shareholders will pay tax thereon. Assuming a tax rate of 28% on eligible dividends, the resultant additional tax is $1.4 million. Consequently, the net amount retained by the individual shareholders after paying both corporate taxes and individual taxes is $7.6 million.

Had the shares of the business been sold, then 50% of the $10 million would have been treated as a capital gain and taxed at an individual tax rate of about 46% (ignoring the lifetime capital gains exemption). This would have resulted in capital gains taxes of $2.3 million (calculated as 46% of $5 million), for net proceeds of $7.7 million.

While the sale of shares would result in slightly higher net proceeds compared to a sale of assets, the sellers should consider that:

- the individual tax portion can be deferred on a sale of assets, so long as the money remains within the business (which can be used for investment purposes); and

- buyers sometimes will pay more for the assets of a business given the tax benefits that they can realize.

Therefore, sellers should retain a qualified advisor to objectively assess the economic outcome of an asset deal vs. a share deal. The above example also serves to illustrate the importance of building “goodwill” within a business.

Other Considerations

There are a variety of other considerations that need to be factored into the assets vs. shares decision. Most notably, an asset deal can be more complex to consummate than a share deal. A share deal offers simplicity in that all existing contracts and employees of the company are automatically transferred to the buyer (although certain contracts, such as licensing agreements, sometimes have change of control provisions). By contrast, pursuant to an asset deal, each existing contract must be renewed under the buyer’s name. This can be both an administrative burden and a source of risk to the seller. Customers having contracts with the company may take the opportunity to renegotiate certain terms of the contract or not to renew.

In an asset deal, each existing employee of the company needs to be offered a new employment contract with the buyer, normally on the same terms as they had with the seller. Some employees may take that opportunity to negotiate a higher salary or better benefits. An employee that does not sign a new contract with the buyer will be deemed terminated, which gives rise to termination costs. The question then becomes who pays for such costs (the buyer or the seller) and the impact that the departing employee will have on the business going forward. This is a particular concern for employees having strong customer relationships or technical knowledge that is difficult to replace.

On the other hand, an asset deal allows the seller to select which assets and liabilities they want to dispose of, without having to undertake a corporate restructuring prior to the transaction. This can be beneficial where the company owns other assets (such as real estate that will not be sold with the operating business) or where the sale of an unincorporated operating division is undertaken.

If the company has losses for income tax purposes, those losses can be used to reduce the corporate income taxes payable on the transaction following the sale of assets. Buyers often are reluctant to pay for tax losses given the risk that their use could be challenged by the Canada Revenue Agency. Therefore, sellers sometimes realize greater shareholder value by retaining tax losses for their own use. This is particularly the case where a business has capital losses, which cannot be transferred to a buyer.

Finally, given that the buyer is exposed to greater risk of hidden liabilities in a share deal as opposed to an asset deal, a share deal normally results in a larger holdback for a longer period of time. Therefore, the provisions of the purchase agreement governing the terms of the holdback become increasingly important.

Conclusions

The choice between a share deal and an asset deal is a significant decision to be made when selling a business. The seller should consider the income tax consequences as well as other factors that could impact the risk profile of the transaction. To the extent that the seller can have some flexibility in how the transaction is structured, it can improve their negotiating position, and ultimately lead to a more attractive deal.