When buying a company, the buyer and seller have to agree on whether to consummate the transaction by way of the shares of the company or its underlying net assets. The conventional wisdom is that buyers prefer to buy assets because of the more favourable tax treatment for them, and to avoid hidden liabilities. Sellers, on the other hand, typically prefer a share deal so that the proceeds can be taxed as capital gains. Therefore, assets vs. shares becomes a key negotiating item.

This guide examines the assets vs. shares issue from the perspective of the buyer.

Quantifying the Tax Benefits

When a buyer acquires the assets of a business, it is permitted to ‘step up’ the cost base of the depreciable capital assets for income tax purposes, thereby generating higher tax savings in the years following the transaction. Therefore, pursuant to an asset deal, the buyer and seller need to agree on the allocation of the total purchase price among the assets being acquired. This can result in considerable negotiation where the target company owns significant depreciable capital assets, such as machinery and equipment, vehicles, buildings, and software that was purchased from a third party (as opposed to being developed internally).

From the buyer’s perspective, the greater the allocation to depreciable capital assets the better, as it will result in a higher tax deduction. Consider the following example. A target company has equipment with a cost base for income tax purposes (termed ‘undepreciated capital cost’ or ‘UCC’) of $1 million. However, the fair market value of that equipment is $5 million (i.e. $4 million higher). The equipment is depreciable for tax purposes at a rate of 30% on a declining balance basis (termed ‘capital cost allowance’ or ‘CCA’) and the buyer’s tax rate is 25%.

If the buyer acquires the shares of the target company, the seller’s tax base carries forward. Therefore, the amount of CCA that can be claimed in the first year is $300,000 (calculated as 30% of $1 million), for a tax saving of $75,000 (based on a tax rate of 25%). The tax shield declines each year afterwards.

The formula for determining the present value of future tax savings in a share deal is:

Therefore, if the buyer’s cost of capital is 15%, then the present value of the $1 million UCC tax base on the equipment is calculated as follows:

By contrast, if the equipment value is stepped up to $5 million, then the amount of CCA claimed in the first year after the transaction is $750,000 (calculated as 30% of$5 million, subject to the half-year rule in the year of acquisition).The resulting tax savings are $187,500. However, in the second year after acquisition, the half-year rule no longer applies. At that point, the tax base of the asset has declined to $4,250,000 (given that $750,000 of CCA was taken in the first year). The CCA deduction in Year 2 is $1,275,000, for a tax saving of $318,750.

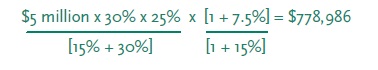

Given the ‘half-year rule’, the formula for calculating the present value of the tax shield on the stepped-up cost of the assets is as follows:

Therefore, the present value of the tax shield on the stepped-up value of the equipment is:

In this example, the buyer would experience an income tax benefit of $612,319 on a present value basis (the difference between $778,986 and $166,667), from buying the assets of the target company as opposed to buying its shares. It follows that the key determinants of the economic benefits of assets vs. shares from a tax perspective are: (i) the difference between the value of the assets being purchased and their existing tax base; and (ii) the CCA rate, which is governed by the income tax regulations.

The example above illustrates why buyers will try to allocate as much of the purchase price as possible to depreciable assets, particularly those that are subject to high CCA rates. However, this results in adverse tax consequences to the seller.

Goodwill

In many transactions, the allocation of the purchase price in an asset deal results in a portion being allocated to goodwill. This is particularly the case for asset-light businesses, such as those in the services industry and technology firms.

Where the buyer acquires the shares of a company, there is no tax benefit for the amount of goodwill acquired. However, pursuant to an asset deal, 75% of the amount paid for goodwill is added to the buyer’s ‘eligible capital property’ account for income tax purposes, and can be deducted at a rate of 7% per year on a declining balance basis. For example, if a buyer pays $4 million for goodwill pursuant to an asset deal, then $3 million (i.e., 75%) becomes deductible for income tax purposes over time. In the first year, the amount of the deduction is $210,000 (calculated as 7% of $3 million – no half-year rule applies for goodwill). The resultant tax savings are $52,500 (assuming a 25% tax rate).

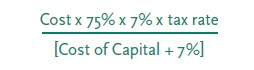

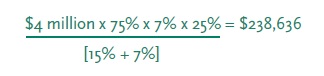

The formula for determining the present value of the tax shield on eligible capital property is as follows:

Therefore, a buyer who pays $4 million for goodwill and has a cost of capital of 15% and a tax rate of 25% would enjoy a tax benefit (in present value terms) of:

As evidenced from this example, the economic value of the tax savings on goodwill is not that significant in relative terms (i.e. compared to allocating the additional $4 million to equipment in our example). Therefore, where the buyer is able, it should allocate more value to depreciable assets. Alternatively, where the target company does not have much in the way of depreciable capital assets, it might be worthwhile to agree to a share deal (subject to other considerations) in order to gain negotiating leverage on other aspects of the deal (such as the aggregate purchase price).

Hidden Liabilities

Buyers are always wary about taking on hidden liabilities when consummating a transaction. Hidden liabilities can materially erode the value of the acquired business. This is particularly the case where the hidden liabilities could be significant, such as those relating to environmental issues and legal claims.

A buyer of shares is exposed to hidden liabilities, whereas a buyer of assets generally is not. There are exceptions to this rule, such as where the purchase of assets is subject to the Bulk Sales Act, which can come into effect in certain acquisitions. However, for the most part, the hidden liabilities issue is a strong argument for consummating an asset deal as opposed to a share deal.

Where the buyer does agree to acquire the shares of the target company, there are certain things that can be done in order to mitigate the risks involved (although not eliminate them). These include:

- increasing the amount of due diligence on the target company. While there is a cost in doing so, the added level of due diligence to detect the possible existence of hidden liabilities can also help the buyer in uncovering other issues that should be factored into the negotiations;

- increasing the holdback amount. In the acquisition of a private company, it is common to place a portion of the purchase price in escrow, in order to protect against hidden liabilities. An amount in the range of approximately 5% to 15% of the purchase price for a period of 6 to 24 months is not uncommon. Where the seller is looking to sell shares, it affords the buyer a better opportunity to negotiate a holdback at the higher end of these ranges;

- negotiating stronger representations and warranties from the seller. These will help to protect the buyer in the event that hidden liabilities are uncovered that exceed the holdback amount, or after the holdback period. In this regard, it is important that the buyer satisfy itself about the seller’s ability to pay; and

- operating the acquired business as a separate legal entity for a period of time following the transaction.

This will help to avoid exposing the buyer’s existing assets to claims that arise in the acquired business.

Other Considerations

There are a variety of other considerations that need to be factored into the assets vs. shares equation. Most notably, an asset deal can be more complex to finalize than a share deal. A share deal offers simplicity in that all existing contracts and employees of the target company are automatically transferred to the buyer (although certain contracts, such as licensing agreements, sometimes have change of control provisions). By contrast, pursuant to an asset deal, each existing contract needs to be renewed under the buyer’s name. This can be both an administrative burden and a source of risk to the buyer (and by extension, the seller). Customers having contracts with the target company may take the opportunity to renegotiate certain terms of the contract or not to renew.

In an asset deal, each existing employee of the target company needs to be offered a new employment contract with the buyer, normally on the same terms as they had with the seller. Some employees may take that opportunity to negotiate a higher salary or other benefits. An employee that does not sign a new contract with the buyer will be deemed terminated, which gives rise to termination costs. The question then becomes who pays for such costs (the buyer or the seller) and the impact that the departing employee will have on the business going forward. This is a particular concern for employees having strong customer relationships or technical knowledge that is difficult to replace.

In some cases, the target company has non-capital tax losses that the buyer might be able to use. Such tax losses only carry forward to the buyer pursuant to a share deal. Caution is warranted, however, as the application of tax losses normally is restricted to income generated from carrying on the same or similar business as the seller, and prior to the expiration of such losses. Therefore, any value ascribed to tax losses should be discounted accordingly in order to reflect the inherent risk in their utilization.

Finally, asset deals sometimes have other hidden costs, such as land transfer tax where the target company owns real property, and provincial sales tax where certain assets are acquired (although the introduction of the HST in many provinces has reduced this issue).

Conclusions

The choice between a share deal and an asset deal is a significant decision to be made in the context of any transaction. While a buyer normally prefers an asset deal in order to enjoy the related tax benefits, such benefits can vary widely depending on the nature of the assets acquired. While an asset deal affords the buyer less risk from a hidden liability perspective, it has to be weighed against the risks of renegotiating key contracts with customers and employee transition.